Favela residents, especially youth, have used online and offline media against human rights violations for a while now in Rio. Media technologies and journalism techniques have been increasingly important components of the struggles of low-income, peripheral populations. In this article, Dr. Leonardo Custódio shares results of his doctoral research on the growth in political organizing thanks to favela media activists since Rio was announced host to the 2016 Olympic Games.

In the years between the announcement of Rio as the 2016 Olympic host city in October 2009 and the recent Olympics Opening Ceremony on August 5, there were innumerable cases when favela residents used media as instruments and platforms for exchanging information to publicly organize diverse forms of political activities.

These include the circulation of community newspapers, blog posts, cellphone videos, documentaries, and photographs denouncing the violence of city officials in evictions. They also include online discussions and mobilizations after cases of police violence. Additionally there were mediated debates that aimed at problematizing prejudice and discrimination against favela residents.

I refer to these phenomena as favela media activism.

That is, the individual and collective actions of favela residents in, through and about media. These contesting actions derive from and/or lead to the enactment of citizenship among favela residents. By engaging in media activism inside, outside and across favelas, favela residents raise critical awareness among peers, generate public debates, and mobilize actions against or in reaction to consequences of social inequality in their everyday lives.

To understand favela media activism we can look at two cases of tragic events and the responses to them before and during preparations for the Rio 2016 Olympics.

The first case happened in December 2008 in Baixa do Sapateiro, one of the favelas in Complexo da Maré, in Rio’s North Zone. Matheus Rodrigues, an eight-year-old boy, grabbed a coin and rushed to a local bakery. As he opened the gate of his house, a rifle bullet hit his head. Immediately after the gunshot, passers-by shouted that a police officer had killed a child. When Matheus’ mother ran outside, she found her son’s dead body by their gate.

The first case happened in December 2008 in Baixa do Sapateiro, one of the favelas in Complexo da Maré, in Rio’s North Zone. Matheus Rodrigues, an eight-year-old boy, grabbed a coin and rushed to a local bakery. As he opened the gate of his house, a rifle bullet hit his head. Immediately after the gunshot, passers-by shouted that a police officer had killed a child. When Matheus’ mother ran outside, she found her son’s dead body by their gate.

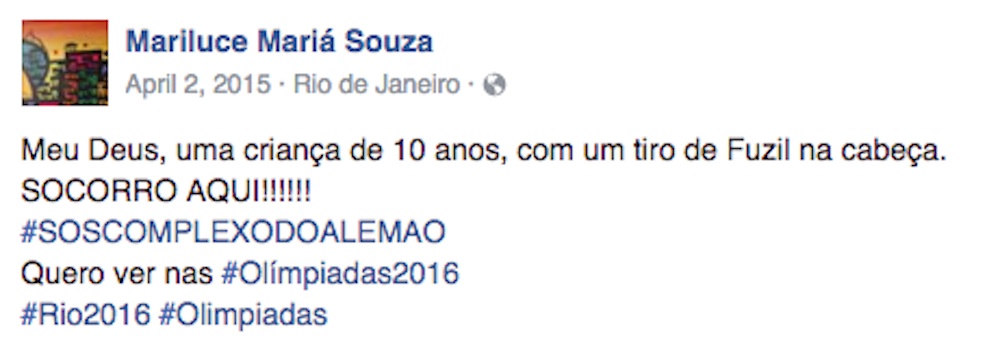

The second case happened in April 2015 in Complexo do Alemão, also in the North Zone. The favela complex had five gunshot victims in less than 24 hours, including 10-year-old Eduardo de Jesus Ferreira on April 2. As in Complexo da Maré, witnesses accused police officers of the shooting.

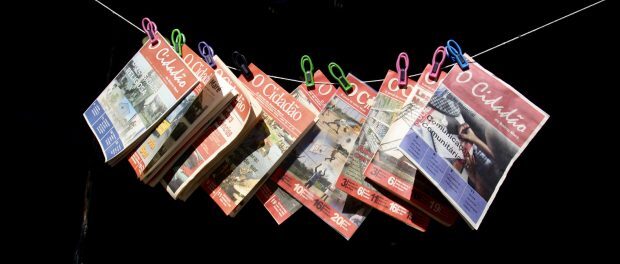

In the case of Complexo da Maré, witnesses to the killing of Matheus Rodrigues immediately called people they thought could be helpful. That included volunteer journalists of the favela-based newspaper O Cidadão (The Citizen). Since its founding in 1999 by local NGO CEASM, O Cidadão has become one of the best-known favela-based newspapers.

Seven years later in Complexo do Alemão, witnesses used Facebook to circulate cellphone videos and photographs of Eduardo de Jesus’ body on the narrow staircase. Some witnesses sent the videos and photos as private messages to media collectives like Coletivo Papo Reto and #OcupaAlemão or to anonymous Facebook pages such as Alemão Morro (which has since changed name and is no longer anonymous) and Jornal Alemão Notícias. Throughout the years these groups have become references of information and mobilization in the region.

In both cases, engaged residents circulated the witnesses’ versions of the crimes within, across, and beyond the favelas. In Complexo da Maré, some volunteer community journalists immediately went to the crime scene to collect witness statements. Others contacted human rights organizations and progressive politicians. Meanwhile, a volunteer photojournalist, Naldinho Lourenço, documented the crime scene in case the police tampered with it before the homicide unit arrived. In Complexo do Alemão, media collectives first circulated the “breaking news” on Facebook and requested more information from followers who lived in the favela. Then they published angry and emotional analyses denouncing the recurrence of state-led violence in favelas.

These immediate reactions represent the instrumentalization of media and journalism for human rights and justice. These resident journalists make no pretense of neutrality. In favelas, crimes against individuals are seen as acts against all residents. One example of this sense of unity is the phrase “nós por nós,” which translates to “it is us for ourselves,” and which activists in favelas have often used to highlight their commitment to the causes of favelas as their main social goal.

After the killings of the boys, volunteer journalists in Complexo da Maré and members of collectives in Complexo do Alemão engaged in simultaneous forms of activism in, about, and through the media.

Activism in the media

In the media, the volunteer journalists of O Cidadão—at that time lacking most of the digital devices available today—produced a written report and distributed it to human rights organizations’ websites, activists’ blogs, other alternative media and also mainstream private outlets. They also used their personal networks to inform mainstream media journalists of the residents’ version of the story, which contradicted with official police statements that the boy was killed in crossfire. A couple of weeks later, they also published an editorial and special report on the crime in the O Cidadão newspaper’s print version.

In Complexo do Alemão, members of collectives circulated information, commented on the cases, and interacted with their extensive base of online followers. One important action of the collectives and anonymous pages was to deny rumors that 10-year-old Eduardo de Jesus was involved in the drug trade. In addition, one member of Coletivo Papo Reto working for Brazil’s biggest media conglomerate, Globo, managed to report on the crime on Globo News, Globo’s all-news cable channel.

Activism about the media

Favela resident activism about the media has emerged from the contrast between the discourses of favela activists and those from the mainstream media. In general, when mainstream media outlets cover crimes in favelas, they tend to rely on official sources for explanations while the voices of residents appear as a dramatic element with more emotional than informational value. This is problematic when the main official sources, the police and the government, are directly or indirectly responsible for crimes.

In Complexo da Maré, for example, mainstream media outlets reported the crime by focusing on its brutality and that residents responded to the crime by blocking roads. They also reported residents’ accusations against the police, but the explanations of the crime itself mainly relied on protocol statements (e.g. “we will investigate…”) by senior police officials.

Similar coverage was seen with the case in Complexo do Alemão. While Eduardo’s parents appeared in tears on various channels accusing police officers of killing their son, the explanations for what happened relied on official government statements. Therefore, mainstream media coverage of crime in favelas tends to concentrate on specific crimes and the immediate reactions of angry residents and bureaucratic officials, as if the questions merely revolved around what happened at a specific moment and why it happened.

By contrast, the core questions in the work of volunteer journalists in Complexo da Maré and members of collectives and anonymous pages in Complexo do Alemão were more structural in nature: why do police crimes constantly occur? Why is there always impunity?

Activism through the media

Activism through media appeared in the organization and mobilization of demonstrations against police violence in favelas. At the time of Matheus’ death, the volunteer journalists of O Cidadão helped organize walkouts that blocked Avenida Brasil, one of Rio de Janeiro’s busiest expressways. They also participated in a demonstration in front of the State Legislative Assembly (Alerj) building days after the crime.

In Complexo do Alemão, the online-offline actions of members of collectives and anonymous pages in articulating demonstrations were even more visible. Following successful mobilization on Facebook, demonstrations took over the streets of Complexo do Alemão after Eduardo’s death. The first one was on April 3 with a couple hundred residents (including children) marching peacefully on the main road of the favela. However, that walkout ended when police officers used pepper spray and smoke bombs to disperse the crowd. On April 4, individuals, media collectives, Neighborhood Associations as well as civil society and human rights organizations organized another demonstration that included residents of other favelas and from outside the favelas.

Favela media activism as an enactment of citizenship

In a broader political sense, favela media activism represents the contesting enactment of citizenship against or in reaction to the material or symbolic consequences of social inequality.

This claim directly relates to the use of “favela” as a prefix to media activism. By using favela as a prefix, I do not simply mean to talk about favelas as urban environments. Instead, I mean to highlight the political and ideological characteristics that separate the actions of media activism in favelas from media activism actions in non-favela environments. Even though there is a lot of collaboration and solidarity among favela and non-favela activists, the conditions and motivations for their struggles are essentially different and irreconcilable.

Non-favela activists defend human and civil rights based on ideals and values. But at the end of the day, many of them enjoy comfort, life stability, and security. By contrast, activists from favelas act against concrete, urgent, and in many ways life-threatening experiences.

So when favela residents react to the killing of children in favelas, they do not do so only because of the belief that what happened is unacceptable according to human values. They do so primarily because the next victim could be them, their family members or friends. They could be the next to be evicted for whatever urban development policymakers decide to promote. It is they who may be discriminated against merely for being favela residents.

My point in highlighting these irreconcilable differences between favela and non-favela activists is not to say that the activism of one is more genuine than that of the other, but merely to indicate that there is a difference. And this difference is not intentional, but structural and cultural.

Engaging in favela media activism represents three forms of contesting citizenship: in relation to the State, to society, and to favela residents in general.

From the State, activists from favelas demand dignified treatment instead of police repression and the general disregard for the welfare of favela residents. In relation to society, they act towards denouncing and deconstructing the general prejudices and discrimination they suffer. Finally, activists from favelas act to challenge their neighbors to see themselves as full citizens. Some favela residents share the prejudices and suspicions against other residents that many people attribute mainly to non-favela populations. For this reason, mobilizing other favela residents can be challenging. It’s not rare that politically engaged residents express their disappointment with the little support they receive within their own communities.

Despite the challenges, there is nothing more promising in terms of citizens’ actions against human rights violations and social inequalities in Brazil than the media activism of low-income, peripheral youth. While it is questionable whether Rio will have the social legacies it promised in its bid to host the 2016 Olympics, it is guaranteed that media activism which has grown during this period will lead to important changes in the currently unequal and unjust city of Rio de Janeiro. The most important of these changes is the political attitude and culture of civic engagement already spreading across favelas and other low-income areas of metropolitan Rio de Janeiro.

*Dr. Leonardo Custódio is a researcher at the University of Tampere, Finland and originally from Magé, a municipality in metropolitan Rio de Janeiro. A longer version of this article is available in his doctoral dissertation entitled “Favela media activism: Political trajectories of low-income Brazilian youth” (click the “Avaa tiedosto” link to download).