There was a project for Rio, an Olympic project, with an international consultancy hired to show how to apply Barcelona’s Olympic Legacy model, highly referenced around the world as an example of the Olympic legacy, to our city. We paid for this consultancy in 1995 and it foresaw a true Olympic legacy for Rio: the restoration of the city’s North Zone with the construction of the Olympic Park on Ilha do Fundão. This was the proposal from the first time that we bid to host the Olympics (Rio 2004). This proposal didn’t win due to the city’s weaknesses (urban mobility, violence and conditions associated with waste and sewage in Rio’s North Zone). For the following candidacy, for Rio 2012, which included the prior hosting of the Pan-American Games, the marketing-oriented model of identifying the construction location found its sweet spot in Barra da Tijuca. The investment also meant a new highway for the city, in order to pioneer this frontier of the city’s expansion: the Linha Amarela, or Yellow Highway.

A dream was born but the project died: our great embarrassment for Rio’s earlier candidacy in the North Zone was during the IOC’s official visit in 1996, when Norwegian Olav Myrhold, an environmental specialist from the International Olympic Committee (IOC), was horrified upon seeing raw sewage openly pouring into the Guanabara Bay from the Cunha Canal. Twenty years later, the solution for this serious problem of Brazil’s image was proposed: instead of changing the Olympic location’s situation, the location was changed! And in a phrase that denotes the huge victory of the Rio and Brazilian people regarding this serious problem, Carlos Arthur Nuzman (president of the COB – the Brazilian Olympic Committee) said about the abandonment of the legacy plan and the decision to host the Olympics in Barra da Tijuca: “now (that) we’re going to greet visitors in the living room, the competition is destined to succeed.” This ignored both the example of the London Olympics, prior to Rio, which successfully revitalized Stratford, a poor district of the city, as well as our original project which was located in the center of the neighborhoods with Rio’s worst Human Development Index figures.

Nuzman wasn’t wrong: the Games were a great success with all the effort, including signs along of the Linha Vermelha and Linha Amarela highways that hid the Rio with its not-so-famous, yet still polluted Cunha Canal, and the neighborhoods that should have been targets of the Olympic legacy. The metro (the most expensive construction project of the Olympics) operated exclusively for those who had tickets, and running along the city’s beautiful and polluted coastline, the BRT TransOlímpica line also ran exclusive bus services which unfortunately weren’t bulletproof. In general, an “exclusive Rio de Janeiro”, or Olympic Bubble as it was nicknamed, helped in the Games’ success.

What stimulated this drastic change in location of the Olympics in the city? The proposal of selling a new Rio, a new city being built in partnership with private initiatives? This city that already made it clear who it is for since the start, since: “How are you going to put poor people there?” as was declared by the owner of the construction company for the Athletes’ Village. Meanwhile the mayor, in the Olympics he built in his mind, claimed that a lot was invested in the poorest part of the city (as was projected in the forgotten plan). But the population from this poor part of the city in the North Zone accumulated their “legacies” and saw them compared to those of the new city of Rio de Janeiro.

The Olympics are over and all of this is history, and, unfortunately for the mayor, in the memory of each North Zone resident who didn’t see what the marketing said. A true war of official notices that tried to prove the City government was right, and the people they govern were wrong, that nothing wrong happened in the North Zone, but which several reporters on their first visit saw. In this case, the “for the English to see” didn’t manage to hide from the Americans, the French, the Polish or any other international media outlet what could be observed on a quick trip through the North Zone. Ramos, a route of these reporting trips, became more than a neighborhood: it became an icon of the suburbs of excluded workers of the “Olympic Legacy” in their own city.

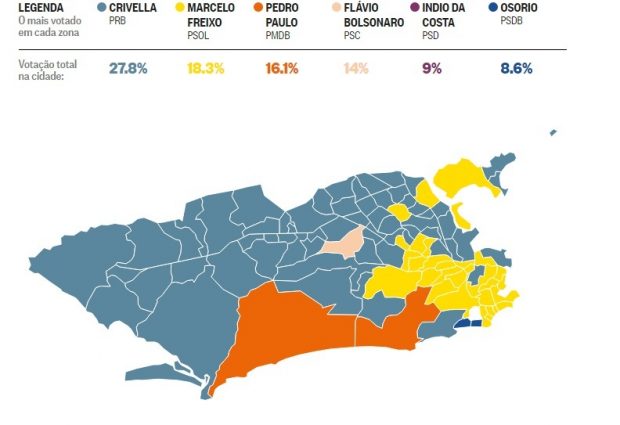

In an election year, the official statements got a platform, with the mayor’s sponsored mayoral candidate, Pedro Paulo, affirming the large investment made in the region with the BRT TransCarioca. In the end, the answer came at the ballot boxes: in the above map it’s possible to see where each candidate for mayor got more votes and where they got less, and it isn’t mere coincidence that there’s a significant percentage of votes for Paulo in Barra da Tijuca and a negligible percentage in the Ramos region, the two neighborhoods featured in this text. They are fruits of the decisions made to build a new city where the poor don’t have a place, and of forgetting the poor also vote even from far away in the “old Rio de Janeiro.”

Hugo Costa, 41, has a degree in Geography from the Federal Fluminense University, is an aspiring blogger and lives in the neighborhood of Ramos in the North Zone of Rio.