The horror of having your life excluded from an official map makes it clear that geography is important in people’s lives. Geography creates a perception of place, of position, and more importantly, of inclusion in a group.

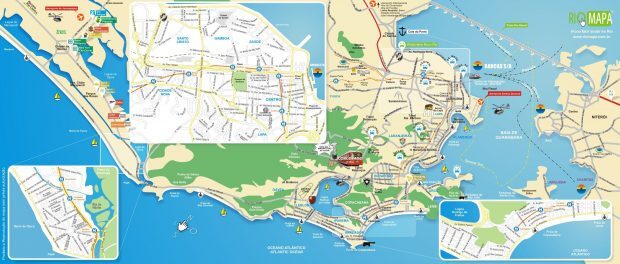

The discomfort of seeing favelas excluded from a tourist map of the city of Rio de Janeiro led to an outburst across the city’s social networks and media platforms this week, as if favelas were an organ that had been excised from the body. No comparison is more fitting, because really a city functions as a body in which each person has their function, carrying information from one “organ” to another (living place).

We’ve already lived eras during which entire organs were removed, physically, like when they ripped out Favela do Pinto for the construction of the (upper-middle-class) “Stone Jungle” condominium in Gávea, relocating people miles away to City of God or Cidade Alta. The consequences are visible to this day: the constructed “cities” (City of God and Cidade Alta) do not feel, for good reason, like part of the city that was left behind: the Marvelous City. We recently relived this in the name of the Olympics, which reproduced techniques from the 1960s and 70s.

But exclusion on the tourist map is not something new for Rio de Janeiro. In reality, tourist maps always showed only the “Marvelous City” and not the parts kept hidden. What happened recently with some favelas has been happening for decades in suburbs of the North and West Zones. Worthless are the 380 years of existing tourism in the Church of Our Lady of Penha, in the neighborhoods of the Leopoldina region, or the fantastic Zeppelin Hangar, which has existed since 1936 in Santa Cruz and is one of a few of its kind still standing in the world. All of these do not appear on the map and even many locals do not visit them.

The most recent chapter dealt with the proposal of the Flamengo Sports Club to construct their new soccer stadium on a plot in Manguinhos, one kilometer from the neighborhood’s train station and on the edge of Avenida Brasil. Decades of absolute silence regarding the abandonment of industrial yards in neighborhoods around Avenida Brasil since the 1970s were ruptured with this announcement, but rather than being seen as an opportunity, it was treated as recklessness: how could they plan an attraction in a place we have always concealed? Which we have always left to fate? Violence, urbanism, and even the target audience were cited as problems, in yet another effort to not “waste” attention on solving the problems of this forgotten region.

More and more, Rio de Janeiro invests in only one approach to tourism, one in which a certain hegemonic class is seen; one in which some people get rich; and which they do not think to reinvent. They spent a lot of money building the Marvelous City, guaranteeing that those who do not fit the right image go to other “cities” within the municipality of Rio de Janeiro—other “cities” they say even have their own rules of administrative management, unrelated to all spheres of official government thanks to its inability to treat all citizens in its territories equally.

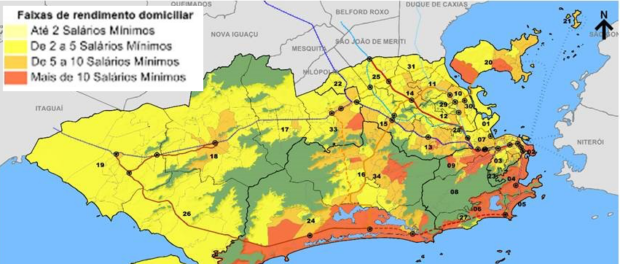

Does the one map reflect the other? Does the tourist map fit with the map of income distribution, and because of this, should we not attempt to identify ourselves in it? Should the tourist map represent less than ten percent of the population, showing only the beachfront areas, without the North Zone or the West Zone and now without the favelas? Showing tourists that even Galeão Airport is outside of the city?

This is no mere coincidence because, as Caetano Veloso sings, “Narcissus finds ugly that which is not in his mirror.”

Geographer Hugo Costa, age 42, is a blogger who resides in the Ramos neighborhood of Rio’s North Zone.