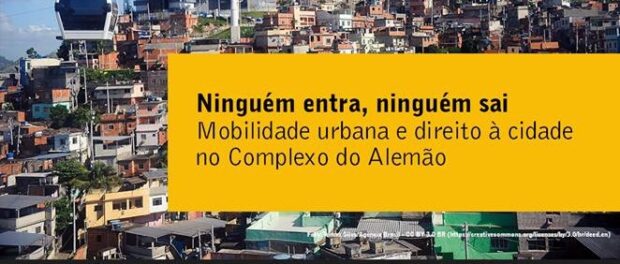

On November 14, 2017, the BRICS Policy Center launched the publication, Nobody Enters, Nobody Leaves—Urban Mobility and the Right to the City in Complexo do Alemão, the result of a partnership between researchers Sérgio Veloso and Vinícius Santiago, from Rio de Janeiro’s Pontifical Catholic University (PUC-Rio), the BRICs Policy Center (BPC), and Coletivo Papo Reto media collective from Complexo do Alemão.

The launch event featured a panel discussion with the book’s two authors, Veloso and Santiago, as well as Thainã de Medeiros from Coletivo Papo Reto and Raquel Barros from the NGO FASE.

The new study sought to highlight two dimensions of mobility: inside and outside the favela. However, one influence on the study turned out to shape the way the research developed: violence. At the end of January, armed conflict intensified and Military Police invaded eleven homes in the Nova Brasilia favela, a strategic point in Complexo do Alemão. This situation led to the temporary suspension of the research project, with modifications to its direction and content. Thereafter, the researchers decided to integrate violence into the study as a key variable. The right to life, which is even more fundamental than the right to the city, became a priority focus.

What does it mean to feel safe in Complexo do Alemão?

Some risks are perceived to be greater outside the favela than inside it, such as the risk of being robbed or approached by police. As such, many people feel a sense of security upon entering the favela. For example, favela resident and Coletivo Papo Reto activist Thainã de Medeiros said he feels more insecure on his daily walk between the metro station and the entrance to the favela than when he is in the favela itself. During this part of his commute, he worries about being searched by the Military Police or being robbed. Still, however, other rights are impeded within the favela itself, such as the right to move freely and be in the street, and even the right to be safe in one’s own home, due to the shootings that can start at any moment.

The State: between presence and absence

“The state does not enter. When it does, it only enters with a rifle,” de Medeiros explained. Simultaneously absent and present, the State of Rio de Janeiro is present in this zone through its armed forces, but is absent in terms of its failure to provide basic public services to the population. The reorganization of bus lines was one of the principal complaints expressed by Alemão residents surveyed for this study, because since the restructuring they have no longer been able to get to the South Zone directly. Other changes to the public transportation network include restricted schedules such that “the train works well in the Baixada (in metropolitan Rio), but on the weekend it stops running at 6pm,” explained Raquel Barros, who said these changes “are other forms of segregation.” The educator from FASE interprets this absence of the state as “a modality of state presence.”

Strategies for getting in, out, and around the favela

Faced with this deficient presence of the state, residents have built collective responses based on the principle of “us for us: I help you and you help me.” Rooted in this ethos, residents themselves have developed transportation services and mechanisms to fill the gaps left by the State. De Medeiros reflected: “The favela resident is the one who moves around the city most, and therefore he must invent new ways of living in it: sleeping in the Central station, jumping the ticket barrier, taking vans.” Moto-taxi drivers also play a key role in residents’ mobility, drawing upon their detailed knowledge of the favela and where they can drive safely. The study found that 57% of the residents of the Grota and Nova Brasília communities of Alemão ride the bus, 12% take mototaxis, and another 12% utilize kombi vans. These strategies, in the context of a failed and absent State, allow residents to circulate and “get by along the edges,” leaving and returning to Complexo do Alemão on a daily basis.