This is the second article in a four-part series on Internet access access in favelas and urban peripheries in Brazil. Don’t miss part one here. For the entire original article in Portuguese by Escola de Jornalismo Énois and data_labe published by Nexo Jornal click here.

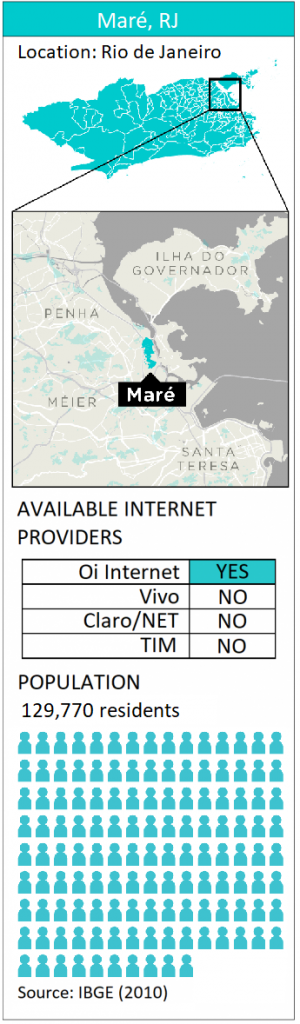

Most traditional Internet providers do not reach Complexo da Maré, in Rio de Janeiro’s North Zone. Only a small part of the favela complex has access to a connection provided by Oi. The majority of the community, which has more than 120,000 inhabitants, remains under-connected. Even if they could afford it, many Maré residents would not be able to obtain a fixed Internet plan, which means that instead they have to rely on illegal wire hookups, the so-called gatos, or mobile Internet plans for cell phones or tablets. There is no infrastructure. The polygon of disconnection coincides with the borders of the favela.

Three kilometers from Maré is the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) campus, where the academic community surfs the Internet using a fixed connection of 100 Mb/s. This is the Internet source that connects some of Maré’s residents in a DIY work-around known as a mesh network. Installed by the Coolab collective, which provides connection alternatives in communities without Internet access, it distributes the connection in a section of the favela by creating a web of wi-fi routers that replicate the signal across the region. The horizontal system forms a network with equal points, and is an inexpensive alternative to circumvent exclusion.

Three kilometers from Maré is the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) campus, where the academic community surfs the Internet using a fixed connection of 100 Mb/s. This is the Internet source that connects some of Maré’s residents in a DIY work-around known as a mesh network. Installed by the Coolab collective, which provides connection alternatives in communities without Internet access, it distributes the connection in a section of the favela by creating a web of wi-fi routers that replicate the signal across the region. The horizontal system forms a network with equal points, and is an inexpensive alternative to circumvent exclusion.

“Because it’s the Internet, we’re talking about basic communication. They are areas that have no [fixed] telephone connection, no communication infrastructure. The important thing is to be able to send a message to someone, organize something, ask for help, a medical request, any kind of emergency… now these people are not isolated,” says Bruno Vianna, one of the members and founders of the collective. “Browsing the Internet itself, accessing information is another layer of advantage: access to education, culture, information, news. All this makes a lot of difference in these places.”

Coolab has already installed the same kind of networks in Amazônia, in Ubatuba on the north coast of São Paulo, in a quilombo and in an indigenous Guarani village. Vianna explains that the installed networks function as a kind of provider managed by the residents themselves, who set the price (if there are fees at all), and take care of maintenance and services. The collective’s idea is to promote localized use of a community network where residents can upload content they produce themselves. In Maré, for example, the work-around can be useful for the safety of projects such as that of the Maré Vive collective, which denounces human rights violations and functions as a community media channel.

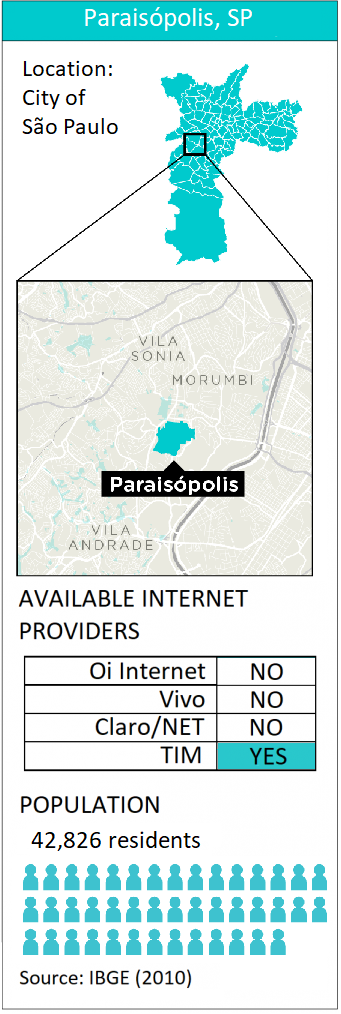

The Paraisópolis favela, in São Paulo’s South Zone, has the same problem as Maré. A symbol of São Paulo’s inequality, surrounded by mansions and high-rise buildings in the adjacent neighborhood of Morumbi, Paraisópolis is the second largest favela in the city and large sections of the community have no Internet connection.

There, among the large telecommunication companies, only Vivo is available. NET does not operate in the region, but does reach neighboring Morumbi. The rest of the area relies on work-arounds: modems with connection points are cloned and, using cables from the adjacent neighborhood, bring the Internet to the favela. That is how, five years ago, Eduardo Ferreira, a former employee of NET and a Paraisópolis resident, began working on how to circumvent the lack of Internet connectivity in his neighborhood.

There, among the large telecommunication companies, only Vivo is available. NET does not operate in the region, but does reach neighboring Morumbi. The rest of the area relies on work-arounds: modems with connection points are cloned and, using cables from the adjacent neighborhood, bring the Internet to the favela. That is how, five years ago, Eduardo Ferreira, a former employee of NET and a Paraisópolis resident, began working on how to circumvent the lack of Internet connectivity in his neighborhood.

Today, he has a company licensed by Anatel (the National Telecommunications Agency) and operates as a small provider in several peripheral neighborhoods in São Paulo, such as Jardim São Luís, Jardim Arpoador, and Carapicuíba. In Paraisópolis, he pays R$15,000 (US$4730) per month for a 1Gb Internet link and redistributes it to 400 clients. For R$50 monthly, each resident has a 10Mb connection, managed by an app on Ferreira’s cell phone.

Not just any work-around, however, can bridge the digital blackout in peripheral areas. In fact, the simple offer of a connection may be considered illegal by Anatel, which does not recommend Internet sharing. In addition, it is a crime to distribute telecommunications services without authorization from the agency.

This is the second article in a four-part series on Internet access in favelas and urban peripheries in Brazil. Don’t miss part one here. For the entire original article in Portuguese by Escola de Jornalismo Énois and data_labe published by Nexo Jornal click here.