Catalytic Communities (CatComm) Executive Director and RioOnWatch Editor Theresa Williamson was invited by Americas Quarterly to write an op-ed on the importance of assassinated City Councillor Marielle Franco as a symbol of and for favela leadership. See the original shorter article here on Americas Quarterly, and the full piece below.

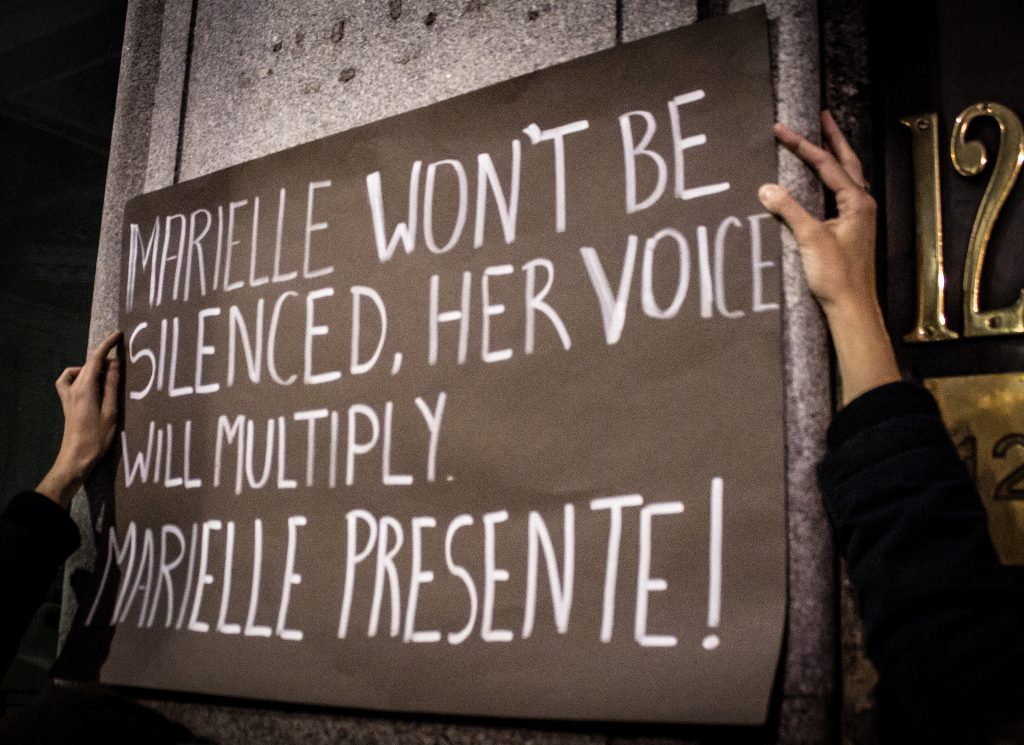

“They tried to bury us but didn’t realize we are seeds.” – Proverb being used widely at events in Rio, across at least twenty Brazilian cities, and around the world in association with Marielle Franco’s death.

Brazil’s slave trade lasted 60% longer than the slave trade in the United States and the nation imported ten times the number of enslaved Africans. One city alone—Rio de Janeiro—received five times the number of enslaved Africans as the entire US, making it the largest point of entry for slaves in history. Brazil was the last to abolish slavery in the Americas, just a couple of lifetimes ago—130 years this May. Fast-growing Rio’s population included 40% slaves at the time. With Brazil among the countries with the most severe land inequality in the world, it was no coincidence that informally settled communities, favelas, emerged as the solution to housing 120 years ago. And it’s no coincidence that in Rio they continue to be the solution to affordable housing today, with 1,000 favelas sheltering 24% of the population. For a century the primary policies towards these communities have been neglect and repression, not because of limited resources or technical ineptitude, but rather through an explicit policy of neglect and repression. Each has been used to justify the other, in a cycle that has become the nation’s default public policy towards the poor, especially black and indigenous peoples, with hyper-visible Rio serving as ground zero.

Why? Because a small elite in one of the world’s most unequal nations, conditioned over generations to see itself as fundamentally entitled to that privilege, has found numerous ways to maintain control of power. 80% of Brazil’s Congress is white, male, over 50 and owners of large fortunes. This elite has gamed the system to maintain the centuries-old slave-holding social structure in place. “Favelas were convenient to have nearby,” I heard a co-panelist and member of the city government say, because they provided “cheap labor close by.” But, he continued, “they are not convenient anymore,” in a moment of speculative land market potential and thanks to Olympic transport investments and federal housing programs that made distant poorly serviced commuter districts possible. How convenient: allow a population to squat to provide cheap labor—to serve you—nearby, but don’t serve them with public services, arguing they are illegal squatters. Particularly notable here is Brazil’s dismal public education system, the best way to maintain the status quo. And then, when favela residents make progress over generations—slowly improving and consolidating their communities, building a vibrant cultural and collaborative fabric, despite the odds stacked against them—inevitably a politician uses their reputation as ‘illegal’ and ‘violent’ as pretext to evict them, forcing them two hours away to public housing and sending them decades back in development rather than investing in local talents and potentials.

This is what Rio did, explicitly, in the pre-Olympic build-up from 2010 to 2016, investing US$20 billion in the city yet ultimately exacerbating inequality with nothing to show in the city’s most marginalized communities, except for the over 77,000 residents who were evicted and the hundreds of thousands suffering greater repression and violent armed control (whether by police, traffickers, or likely a sinister and mutually reinforced combination of them both).

And except, that is, for one of the few silver linings to come from the pre-Olympic years: the strengthening of community leadership.

Enter Marielle Franco. Assassinated most likely by police actors, or ‘exterminated’ as many are now saying, last Wednesday night in central Rio, City Councillor Franco represented a direct and powerful affront to this system: someone who crystallized in one person the groups meant to ‘stay in their place’ in Brazil. As The Brazilian Report summarizes, in Brazil a black youth dies every 21 minutes, a woman every other hour, an LGBTQ person daily, and a human rights defender every five days. Franco was all of these. A 38-year-old black LGBT woman from a favela in Complexo da Maré, a single teenage mother who went on to study sociology and receive a Masters degree in Public Administration, coordinate the state government’s human rights division and just over a year ago win election with the City Council’s fifth largest vote count, or 46,000 votes, Marielle was a force of nature (and still is, as we are now witnessing). Rather than, at best, black women sitting on the bleachers at City Council meetings, there was now a black favela woman, with her beaming and captivating presence and her incredible courage, behind the podium. And she was using it faithfully, daily, effectively, to call out police abuse, to confront gender violence and a host of other deep-rooted issues. In her 13 months in office she introduced 13 laws. A voice on issues deemed inconvenient enough by someone to justify taking her life. Just two weeks ago she had been selected to lead the City Council’s special commission to monitor the federal military intervention recently declared for Rio. Franco vehemently opposed the intervention, which places security entirely in the hands of the army, a force even less prepared to handle a civilian urban reality than the state military, civil, or municipal police forces, often associated with corruption and based on centuries-old institutions.

Franco’s decision to run for office took place on International Women’s Day in 2016, half a year before her election. As a human rights defender, she was on a panel on ‘Women in the City’ just hours after Maria da Penha’s house had been demolished in the iconic favela of Vila Autódromo, a small community that fought vehemently against pre-Olympic evictions that would have benefited Brazil’s biggest real estate tycoons. Petite but overpowering in her faith that she and her neighbors would prevail, Penha became an international icon of resistance and coined the phrase commonly associated with the community’s struggle—”Not everyone has a price“—referring to her unwillingness to consider any compensation for her home, since money had nothing to do with its value. Penha was supposed to sit on the same panel as Franco but missed it in light of her loss, though she went on to win an award on that incredibly emotional day. It was in this context that Franco decided to put her name in the hat.

Rio’s favelas have been built by their residents since they first formed generations ago. Leadership is key to their struggle, with individuals taking on roles of organizing residents to make improvements, engage with the authorities, and beyond. Franco came from Maré, a community with a very engaged and diverse civil society. She was fruit of a new, particularly extraordinary emergence of favela leadership, hundreds of new fantastically networked and collaborative organizers that have been maturing and consolidating their individual and collective missions, and which have only been further galvanized by her assassination. They are, among other things, avidly using social media to break Brazil’s media monopoly. These leaders are adamant, as Marielle was, that “the favela is not the problem. It is the solution.” The solution to affordable housing and marginalization, to neglect and repression. Favelas are built on resilience and resistance, and young leaders are increasingly reclaiming with pride the very term ‘favela,’ apt given its origin in the robust, resilient, and spiny favela bush, and given all these communities have accomplished through self-organizing.

One of Franco’s final tweets read, “How many more will have to die for this war to end?” The same question was posed after her death on Wednesday. And two days later, on Friday night, the same question was posed again when a one-year-old boy and a 58-year-old woman were killed in a shootout involving police in Complexo do Alemão, a community teeming with innovation and youth leadership you’d never know about if you stuck to the major headlines. (The role of the media in perpetuating the myths around the ‘favela problem,’ and thus justifying policies of neglect and repression, is another issue.)

One army colonel has argued publicly against the ‘martyrization’ of Franco, clearly oblivious to who this woman was, who and what she represented, the experience and sheer number of people who felt reflected in and represented by her, and her beyond-life force of nature. The truth is: something has fundamentally shifted. Franco was on the rise and sadly there is no way of knowing how far she would have gone alive. The experience of her death by those who learned from, and felt represented by, her is nothing less than akin to the experience of losing Martin Luther King Jr or Malcolm X. (In fact she died just seven months short of King’s age at death and 13 short of Malcolm X’s.) But now, everyone knows her name. Now there’s a hunger, to know who this woman was, what she stood for, what issues she was working on that would lead her killers to take such action. She was an illuminated human being and has become a symbol and an inspiration, affirming the black favela woman as a source of admiration and courage. She is now a part of you, reading this, and you are made a little bit better by the fact of her existence. Millions of seeds of insight and determination are being planted with every thought, feeling, sharing of her message, her beaming face and her forceful presence. It is inevitable that Brazil will be transformed. The question is, how many more have to die?

Theresa Williamson is an urban planner who has been working with Rio’s favela communities since 2000. She is founder and executive director of Catalytic Communities (CatComm), an empowerment, communications, think tank, and advocacy NGO founded in 2000 in support of Rio’s favelas. She is also Editor-in-Chief of RioOnWatch, Rio’s bilingual favela reporting news site.