This is the fourth article in a five-part series on community museums and resistance in Rio’s favelas in honor of Brazil’s 16th Annual Museum Week (May 16-20, 2018).

“The aim is to uncover and exhibit every trace and every scar of [the community’s] history, and reconstruct memories through the voice of the residents in order to assert their identity.” – Horto Museum

According to historian Laura Olivieri, Horto Florestal had three phases of occupation. The first inhabitants of the area were enslaved Africans brought to work on the sugarcane plantations in 1578. In the 18th century, laborers were brought to the area to work on a coffee farm, and finally the creation of the Botanical Gardens in the early 19th century meant more slaves and laborers were brought in to build and maintain the gardens. They were offered plots of land for themselves and their families, and permission to build houses on them in order to be close to their work. Today, Horto is largely made up of descendants of these groups of people. However, since the 1960s, the community of approximately 2,000 residents has been battling threats of eviction.

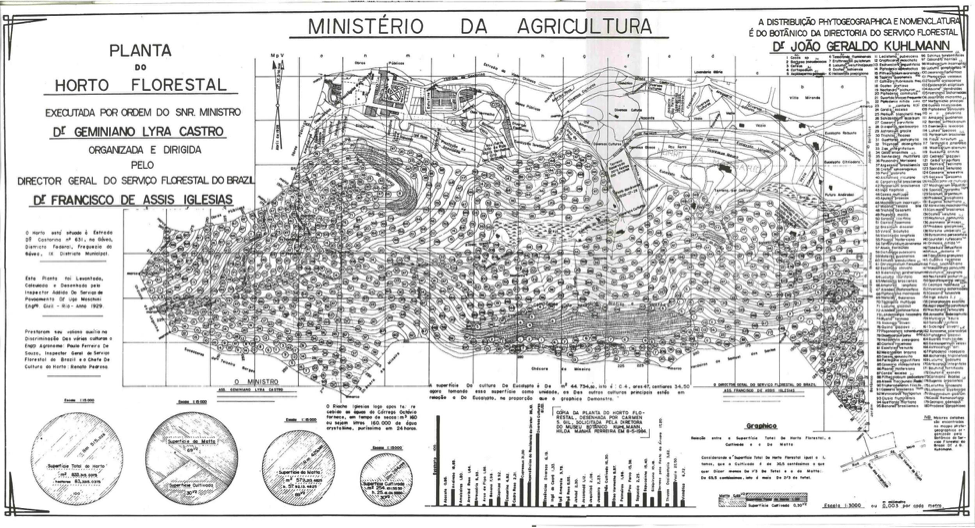

Community members live on land called Horto Florestal, which has been linked to Brazil’s Society of Forests and the Ministry of Planning since 1875. A 1929 map of the area shows the perimeter of Horto Florestal to be 83.3 hectares and demarcates a clear boundary between this area and the 54 hectares owned by the Botanical Gardens. This boundary has become the object of a long-standing, federal dispute between the community and the Botanical Gardens administration. On the one hand, the Botanical Gardens administration uses an environmental conservation discourse to explain why it wants to ‘reclaim’ the land of Horto Florestal to grow the research and conservation activities of its research arm, the Botanical Gardens Research Institution (IPJB). The official stance, as articulated by the president of the Botanical Gardens administration Sérgio Besserman, is that the community’s presence “is not compatible with a functioning research institute.” He claims that “we are not expanding, we are taking back land which already belongs to the Botanical Gardens. This includes the community’s land, which even the community itself considers an occupation of the Botanical Gardens’ land.”

The property development in the surrounding neighbourhoods of Gávea and Jardim Botânico has made this argument unconvincing. In addition, O Globo has reported the value of Horto’s land at R$10.6 billion (around US$2.9 billion), fueling suspicion that the real motive behind eviction is real estate speculation.

In direct contrast to what Besserman claims, the residents of Horto insist on their status as an established community on the land for over 200 years. The Horto Museum presents a counternarrative to the Gardens’ retelling of the area’s story by documenting proof of human occupation of the land since the late 1500s. In doing so it produces evidence that asserts the community’s right to the land, and support for its resistance movement against eviction.

In August 2016, Horto was issued a 90-day eviction notice. This ruling came in spite of the agreement made during the previous federal government administration under Dilma Rousseff to a land regulation plan, which would give residents legal rights to their homes and allow them to remain in Horto Florestal. The justification given for the eviction of the Horto community was twofold: they are ‘invaders’ of the land and pose a ‘threat’ to the preservation and the sustainability of the Botanical Gardens. This narrative has been woven into legislation and promoted by the Brazilian media conglomerate, and Horto neighbor, Globo. It wasn’t until 2006, however, that the federal government also started using the label of ‘invaders,’ but always without, as journalist Anne Vigna notes, specifying the date of invasion.

The Globo Network, which established its headquarters in the neighborhood Jardim Botânico in 1965, promotes this narrative, allowing it to permeate public consciousness and establish itself as ‘historical fact.’ News headlines are deliberately phrased as endorsement for the Botanical Garden’s rhetoric: “The illegal occupation of Rio’s Botanical Gardens is an imbroglio that has lasted decades” (1986) and “The invaders suffer a defeat” (2012). Articles contain similar statements within, such as the statement that “there is yet another movement looking to guarantee the residence of the invaders” (2017). Residents and activists point to Besserman’s role as environmental commentator on GloboNews as reflecting the media conglomerate’s vested interest in the Botanical Gardens’ side of the dispute.

A museum to contest the accusations

The Horto Museum, like other community museums, describes itself as an ecomuseum. Visitors are invited to personally experience the history of the neighborhood through tours led by community members associated with the museum. The museum archive is available online and contains an extensive selection of sources such as maps, photos, videos, oral histories, newspaper clippings, and songs. The information is organized by theme—such as music, politics, religion, and resistance—and by the type of documents, which are referred to as “memory supports.” The term “supports” highlights the way in which the museum has been a vehicle through which the community can record its memories in an authoritative way. As evidenced by this article’s opening quote, the emphasis is placed on understanding the community’s history from its own perspective. Emerson de Souza, Residents Association president and director of the Horto Museum, expanded:

“The museum provides an armor for the story of this community as well as importance and legitimacy to the people who participate in these stories.”

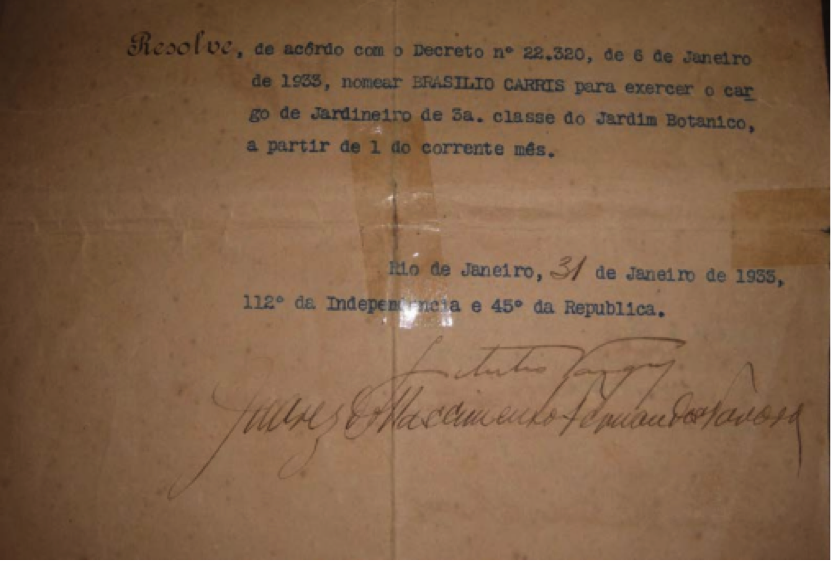

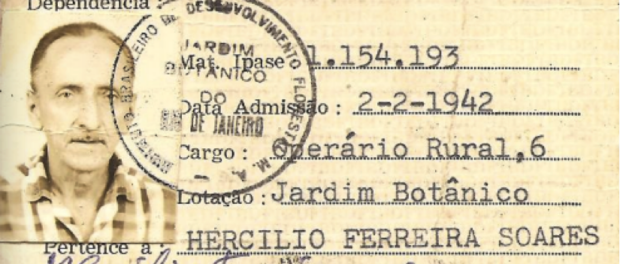

The archive’s primary concern is recording the long history of the community. In addition to sources such as maps, photos, videos, oral histories, and newspaper clippings, the archive includes a dossier written by historian Laura Olivieri Carneiro de Souza. The dossier is explicit in its aim to “defend the community’s historical connection to the land and its infallible right to reside there” and provides extensive supportive evidence, including photos, maps, government documents in favor of Horto’s presence, newspaper articles, oral histories, academic texts and studies of the area, and identification cards, which directly counter claims that the residents are invaders of the land.

As Souza summarized, “The Horto community was created to protect the environment, not to destroy it.” The archive also counters official claims that residents pose a threat to the environment. Aside from documentation proving that many residents’ jobs involve working to maintain the gardens, it contains records of the community’s participation in global environmental initiatives such as ‘Clean Up the World.’ The museum also directly addresses Globo’s smear campaign in a section entitled “Globo’s defamation campaign against Horto’s residents.”

The resistance to the State’s conservation discourse presents itself in the very language residents use to describe the evictions. They express how their families have been “cultivated” in Horto and live “completely integrated in nature.” The threat of eviction would “yank them from the soil” where they have laid their “roots.”

There are four different tours offered by the Horto Museum, each to a different site of memory and each placing a strong emphasis on the historical roots of the community. Option one, “the tour of the mill,” for example, takes visitors to the ruins of one of the first sugar mills in Rio de Janeiro, which dates back to 1575. Option three is “the tour of the ancestral trees,” which is a trek through the forest to where the indigenous, African, and Afro-Brazilian ancestors of Horto’s residents would perform their rituals. The tours are led by a museum leader who narrates the history of the community, pointing out interesting flora and fauna and sharing stories about how Horto used to be and how it has changed today. “We usually do these tours on the weekend when people are home so we can knock on their doors and talk to them,” explained Souza.

In this way the Horto Museum not only presents a counternarrative through asserting Horto’s historical roots in its archive, but enables visitors to actively participate in the residents’ history. Through its tours, the museum provides a multisensorial experience that allows visitors to engage with history through their bodies in a way that could not be done either in a national museum or with a history book. As such, it is not just the museum archive that “conveys authority and sets the rules for credibility,” as historian-anthropologist Michel Trouillot puts it, but the visitor embodies a subjective reality and, in doing so, reinforces local collective memory.

The final case study in this series, to be published tomorrow, is on the Evictions Museum in Vila Autódromo, which stands as an example of what a museum can do for current and future resistance movements against eviction.

This is the fourth article in a five-part series on community museums and resistance in Rio’s favelas in honor of Brazil’s 16th Annual Museum Week (May 16-20, 2018).

Gitanjali Patel is a researcher and translator. She has an MA in Social Anthropology from SOAS, University of London. Her research looks at memory and the production of history in Rio’s favela communities.

Full Series: Museums of Counternarratives and Resistance

Part 1: Brazilian Museums In Context

Part 2: A New Kind of Museum

Part 3: Maré Museum

Part 4: Horto Florestal

Part 5: The Evictions Museum