On Saturday, June 23, the 11th Rio Forum took place in São Gonçalo. The Forum is a meeting organized by Casa Fluminense, a civil society organization working to improve coordinated and participatory planning across the municipalities of the Rio de Janeiro metropolitan region, bringing together a network of movements and activists from the 21 municipalities in the metropolis and discuss public policy proposals. The event marked the launch of Rio as a Whole–a nonpartisan movement to increase citizen participation in the electoral process, incentivize transparency, and promote social control of public administration. This initiative is part of an “effort to put forward a positive agenda for the city,” as stated by Henrique Silveira, executive coordinator of Casa Fluminense.

“The movement emerges in the context of distrust in politics, hollowing institutions, and the detachment of social participation from institutional policy,” explains Maria Luiza Freire, project coordinator at the Intelligent Citizenship Foundation–an organization spearheading the movement alongside Casa Fluminense. One of their instruments is an online platform through which candidates can make pledges in favor of proposals submitted by organizations and supported by citizens. On the platform, users can “match” with candidates who support proposals that they prioritize, reminiscent of the dating application Tinder.

“Beyond being a space for dialogue between organizations, citizens, and candidates, and helping with voting, the platform also incorporates content that helps to make the functioning of the electoral process more transparent. This is all in a context in which monitoring and participation are made difficult due to constant changes in electoral regulations–Brazil has never had more than two elections that have followed the same electoral rules,” Freire explains. One such change in the upcoming election is the reduction of the campaigning period from 90 to 45 days.

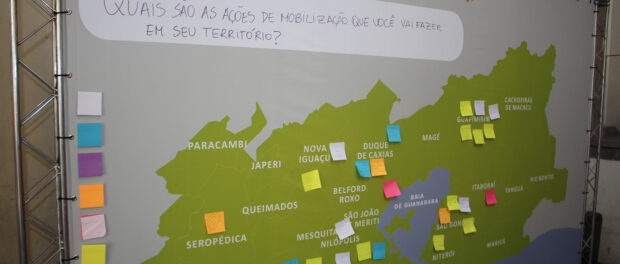

This digital solution reflects the growing influence of technology and social networks in the political process. This is especially relevant in the context of Brazil, one of the three countries in which people spend the most time connected–nine hours per day, on average. “We need to understand the importance of technology [for these elections], but without fetishizing it,” Silveira warns. This is why the Rio as a Whole initiative also promotes mobilization in its territories. These actions include the upcoming public class on the topic of the Santa Cruz University Pre-Vestibular (college entrance exam preparatory course) on July 10, and the São Gonçalo as a Whole Bike Ride, organized by the São Gonçalo Cycling Union and the Social Funk Network, on August 3.

The Rio Agenda 2030 proposals, which were also launched at the Forum, are already available on the platform. Since its founding, Casa Fluminense has put forth an agenda of proposals each election year to enrich civil society debates and demand commitments from candidates. The previous version of the agenda, entitled Rio 2017, directly countered the Olympic slogan “Rio 2016” and sought to envision Rio de Janeiro after the mega-events. The current version results from the accumulation of Casa Fluminense’s experiences, together with over 50 partner organizations. The Agenda expands the horizon beyond the next state administration, reemphasizing alignment with the international sustainable development agenda proposed by the United Nations (called the 2030 Agenda)–thereby contributing to its implementation in Brazil.

The result is a set of 40 proposals based on real demands, organized along eight broad axes including employment and income; urban mobility; public security and the right to life; sanitation and access to healthcare; education; and culture. The proposals are driven by the motto of Rio as a Whole: more opportunities and fewer inequalities. “Marcos Vinícius is present in the Agenda’s proposals. Today they seek to understand the consequences of inequality, which have materialized in the death of Marcos. We are looking at causes–at the rate of schooling [in these territories], at security policies,” explains Vitor Mihessen, information coordinator at Casa Fluminense, in reference to the assassination of the 14-year-old boy by Civil Police during an operation in Maré three days before the Forum.

In response to police operations with tragic consequences such as the death of Marcos, Redes da Maré, together with the Human Rights Defense Nucleus at the Public Defender’s Office, proposed a civil public action to the Public Defenders Office in order to demand from the state government a security plan specific to their territory. “We are tired of acting in response to emergencies; we want medium- and long-term actions. Mobilization needs to be permanent. We produce a great deal of knowledge, but it’s not carried through. We need to hack the system. Is it a report that they [the Public Prosecutor’s Office] want? So we’ll make a report and present the facts. We’re tired of just marching. We want to guarantee things that are foreseen in the law–the presence of ambulances during [police] operations, cameras and GPS systems in vehicles, operations that do not take place at night,” says Lidiane Malanquini, coordinator of public security issues at Redes da Maré.

“Homicide is just the tip of the iceberg, there’s a series of other violations. How many people have lost their jobs because they arrived late due to [police] operations? We now issue certificates for residents, stamped and signed, explaining to employers that there was an operation. When we are not creating permanent solutions, in the meantime, we have to try to reduce harm. Since they did not present a plan for harm reduction on time, we made our own. If the State does not do it, the people of Maré will,” Malanquini adds.

During the same week as Marcos’ death, statistics on violent deaths in Brazil from the Atlas of Violence were revealed. Two municipalities in Baixada Fluminense topped the list: Queimados, in first place with 134.9 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants, and Japeri, in sixth place with 95.5 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants. The average for the metropolitan region is 43, and the Agenda lays out a goal to reduce that number to 10 deaths for every 100,000 inhabitants by 2030. Moreover, homicides are now considered an epidemic by the World Health Organization. “Our goals, the numbers that we want, are on the horizon. When you think about it, these numbers are people–our own lives are reflected in the metrics. It is necessary to consider how this inequality speaks volumes about these lives, about these bodies, and how this inequality can be deadly,” says Mihessen.

“We are not violent, we are violated, including by a lack of public policies,” says Carlos Greenbike, activist and founder of Pedala Queimados–which promotes active transportation in the city and actions that pursue the social transformation and appreciation of the territory. He is also the founder of the project Anda Queimados – Walks in Nature, which, beyond integrating inhabitants with nature, also seeks to attract tourists to the region. “How can Queimados become a real tourist destination if people perceive the city as dangerous?” he asks.

“If there were more culture, leisure, and education in this area, maybe the Baixada Fluminense would not be the stage for this,” suggests Fábio León, communications advisor at the Grita Baixada Forum. The Agenda recognizes that reducing inequalities is only possible by providing access to these services and resources. This perspective is emphasized in the words of Maria Josélia, founder of Projeto Aprender (the Learning Project) in the community of Pica-Pau, in São Gonçalo: “I became literate at 27. One day, I suffered an accident and spent time away from work. In my free time, I began to provide educational reinforcement to the children of the favela of Pica-Pau. What future will these children have if they do not finish school? And how will these children get up every day to go to school without breakfast?”

Another testimony in this vein is that of cultural producer Taty Maria: “The problem is that culture is not seen as a right but as a privilege. There was a group of boys from Morro da Caixa D’Agua who spent all day outside of the Dicró Arena in order to use the Wi-Fi. One day, we invited the boys to enter. And they asked, ‘Can we go in like this?’ pointing to their casual clothes and flip-flops.”

Yet more, the Agenda puts forth proposals to confront structural racism and promote gender equality and respect for sexual diversity. In addition, it contains proposals to create more public green spaces where people can meet; expand recycling with the inclusion of compensated waste collectors; and prevent flooding and expand the sanitation system, with the goal of doubling access to sewage treatment. “In Jardim Gramacho, we have a serious problem with pollution from an old garbage dump, which is invading and contaminating a mangrove swamp,” explains Jovelita Miranda, who is a resident and leader of the movement SOS Jardim Gramacho–the favela in Duque de Caixas where the deactivated landfill is located.

The agenda also contains proposals for developing social interest housing policy, including creating housing in central areas on underutilized properties; increasing the viability of public housing in densely populated areas with urban infrastructure; and reviving and universalizing favela urbanization and land regularization. This includes technical, legal and administrative assistance–and the participation of residents throughout the process–in order to combat eviction policies.

“We have no way of thinking of strategies for change without listening to those who live in the [affected] region. That is how we differ from the way of politicians–only showing up in favelas at critical moments during elections. Based on the work that we do, we think of significant changes made by local agents themselves,” says Fabbi Silva, a resident of Parque das Missões in Duque de Caixas and leader of the initiative Sponsor-a-Smile Soirée.

“I have nothing against partisan politics. To the contrary. However, I believe that we need more of our people on the inside so that we can make an impact in favelas. But I understand that social policies made in communities need to be solidified–we need to work in a network. We need to begin to talk with one another and strengthen the work that each person is already doing in their territories. This is where [the Agenda of] Casa Fluminense and its platform come in. We need to get out of this realm of promises and enter the sphere of actions. The problem of Parque das Missões is not exclusive to Parque das Missões, the problem of Jardim Gramacho is not just the problem of Jardim Gramacho. It is a problem of society as a whole, a problem of the State,” Silva concludes.