This is the first article in a six-part series that comprises the book chapter entitled “Not Everyone Has a Price: How the Small Favela of Vila Autódromo’s Fight Opened a Path to Olympic Resistance” recounting the story of Vila Autódromo’s struggle. Written by Theresa Williamson, executive director of Catalytic Communities,* the chapter is part of the book ‘Rio 2016: Olympic Myths, Hard Realities‘ edited by economist Andrew Zimbalist. To read our review of ‘Rio 2016,’ click here. RioOnWatch would like to thank Brookings Press for providing the permission to republish the chapter here in its entirety.

It was exactly one hundred and twenty years ago. As history, now thoroughly intertwined with legend, has it, downtrodden soldiers, poverty-stricken and scarred after the long, bloody battle of Canudos, Brazil’s deadliest ever civil war, headed from Bahia to the nation’s capital at the time: Rio de Janeiro. The soldiers, formerly slaves who’d just been freed and then immediately drafted for the fight, had been promised land there for serving in battle.1

Rio de Janeiro was one of the world’s largest cities in 1897 and certainly the largest in Brazil, with over half a million inhabitants. Brazil urbanized relatively early for a developing nation, and Rio was the first major city to do so. Due to its importance as both the nation’s fastest-growing city and federal capital, land there represented a major opportunity.

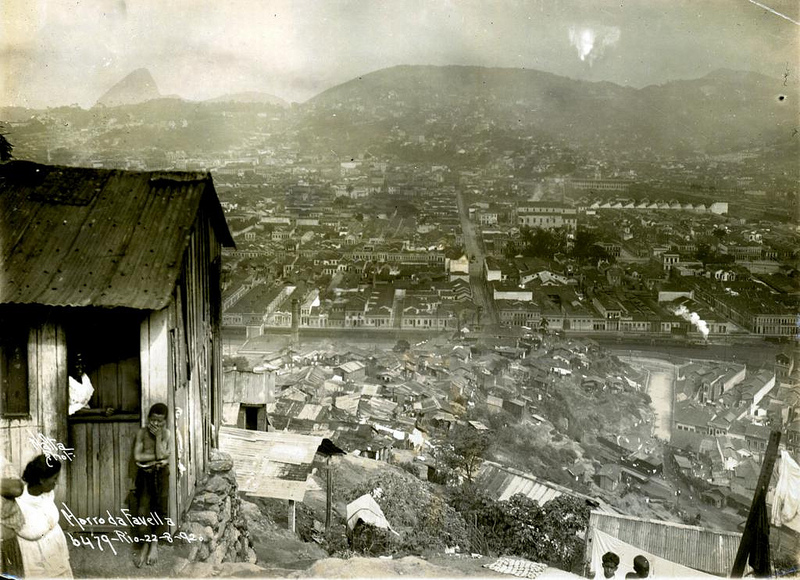

But as they arrived, soldiers found no such land set aside for them, so they squatted outside the Ministry of War in downtown Rio, awaiting what would turn out to be an empty promise. Weeks later, a colonel with some land on a nearby hill in Rio’s downtown port area gave them permission to squat on his hillside. And so they climbed up the hill and settled, naming their settlement Morro da Favela, or Favela Hill, after the robust, spiny, oily, and flowering Favela bush that had characterized the Canudos hills where they had served in battle, hills also named after the Favela plant and where some of them had met their wives. They thereby coined favela as the go-to word to describe Brazil’s informal settlements, which became the mainstay of affordable housing in Brazilian cities during the century to come.

Over the subsequent decades, more and more rural migrants and former urban and rural slaves and their descendants joined the Canudos soldiers in occupying Rio’s hills,[a] and all of Rio’s informal settlements became known as favelas, so Morro da Favela changed its name to Morro da Providência, or Providence Hill. Despite attempts at eviction throughout its history, the residents of Providência have resisted, and the community celebrates its 120th birthday this year.

Sprouting initially on central hillsides and later in peripheral low-lying areas as the city expanded—nearly always on public land—favelas came to be such an integral part of the city that, by 2012 when Rio’s landscape was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site, UN Special Rapporteur on Adequate Housing Raquel Rolnik declared “Rio’s favelas between the mountain and the sea” an integral part of that world heritage status. Georgetown University’s Brazil historian Bryan McCann explains: “about the only things that today’s Vidigal (a favela in Rio’s South Zone) has in common with the same neighborhood in 1978 is the absence of property title and the continuing discrimination against its residents, yet everyone still recognizes it as a favela.”2

The century in between was marked by a number of policies toward Rio’s favelas, the primary policy being one of neglect that led to these communities’ marginalization.3 Descendants of slaves who comprised the bulk of the favela population were not deemed full citizens and favelas were, as a result, described as “backward, unsanitary and over-sexualized.” They were deemed “illegal” occupations and thus it was argued they were not entitled to urban improvements. Yet they were also not terminated for the most part and were even encouraged at times because they “offered cheap labor nearby,” as a municipal official informed a Rio audience in April 2014; as he also explained, this was “convenient, until now.” Thus, one can summarize policy toward favelas historically as one of finding ways to maintain the structure of a slaveholding society, even post abolition.

Three other broad and interrelated policies were applied toward Rio’s favelas in the twentieth century. The first is a policy of forced eviction, which was mainly applied under Governor Carlos Lacerda during the military regime between 1962 and 1974, when 140,000 people were removed from their homes, though the fear of eviction has characterized favela residents’ experiences from day one until now.4[b] Second were sporadic, incomprehensive, and insufficient upgrading policies, intended to provide minimal infrastructure in some favelas, with the most robust program, Favela-Bairro, taking place in the 1990s. Third has been a policy of criminalizing and repressing the urban poor, with Rio’s Military Police as its principal enforcer, dating back to the institution’s founding in the first decade of the 1800s and compounded during the institution’s history. Today, favela residents regularly criticize the occupation of favelas under the current Military Police’s Pacifying Police Units program as the only arm of the state residents experience, when they “always demanded long-term policies” and what they “want [is] the end of open sewers and of electricity and water outages.”

Over a century, however, favela residents did not all remain passive recipients of such policies. Instead, they have increasingly organized and reacted. Vidigal, in Rio’s South Zone, is notable in its early resistance to eviction during the military regime, which essentially halted the regime’s forced eviction campaign in 1978.5 And housing groups that grew out of the decades of insufficient affordable housing and poor policies led a movement that secured adverse possession as a clause in Brazil’s new “People’s Constitution” of 1988, and other forms of housing rights in state and municipal laws to follow.16 In addition, by the 1990s a trend began which is now widely held, among the Brazilian architecture, engineering, and urban planning establishments, to view comprehensive and participatory favela upgrading as the correct policy approach to improving the lives of residents.

As a result of this history, today Rio de Janeiro is the Brazilian city with the largest number of people living in favelas. Approximately 1,000 individual favelas, ranging in size from hundreds of residents in small communities like Recreio II, which was removed for the TransOeste bus corridor and highway in the West Zone, to 200,000 in Rocinha in the city’s South Zone, comprise the 1.5 million favelados, or 24 percent of the city’s population, living in favelas.

And in fact, despite significant challenges to comprehensive upgrading that would guarantee quality public infrastructure and services in these communities, there are numerous qualities—urbanistic, economic, and sociocultural—that have developed out of informality in Rio’s favelas.6 Favelas naturally tend to be characterized by a number of qualities that urban planners around the world are currently working to integrate into sustainable communities but often have a hard time building into already-consolidated urban centers: affordable housing in central areas, housing near work, low-rise/high-density construction, mixed-use developments, pedestrian-first roads, high use of bicycles and transit, organic (flexible) architecture, high degree of collective action and mutual support, cultural incubators, and a high rate of entrepreneurship, among other factors. In fact, during Brazil’s recent ten-year boom, favelas fared better in developing than society as a whole on average.

Unlike other developing regions, namely in Africa and Asia, which have been urbanizing in recent decades, Brazil’s population has been more than 80 percent urban since the 1990s. Given their presence in Brazil’s fastest developing early city, favelas in Rio are thus some of the most long-lived informal settlements (still seen as such) in the world today. Their struggles, successes, and challenges thus offer incredibly rich sources of wisdom and knowledge, inspiration and warnings, about what can happen when communities are left to develop themselves over a long period of time. Urban planners and international development practitioners are starting to pay attention to what can be learned from these communities, what sort of innovative new treatments are necessary to ensure their effective integration without compromising community attributes, and how their stories can inspire a new approach to city-making in the decades to come.

Despite this reality, a deeply biased and inaccurate narrative dominates the view of Rio’s favelas locally and around the world.[c] In the early 1900s, shortly after their settlement, favelas were labeled “backward and unsanitary.” Such views quickly found their way into the monopolistic Brazilian media narrative, where they were consolidated over many decades through to the present day. Maintaining a public perception of favelas as inherently illegal, criminal, precarious, and unmanageable allowed for the perpetuation of an image of these communities as temporary and in need of dramatic punitive intervention, whether that be through evictions or policing, and has allowed the authorities to maintain a policy of neglect and poor upgrading, which further exacerbates community challenges, keeping favelas in a never-ending spiral of legitimized neglect. Meanwhile, as an important world city and tourist destination for two centuries, Rio has always been of interest to international news outlets, though not important enough to dedicate significant resources to it. As a result, historically the global media picks up on the dominant local media narrative and amplifies it via telephone or parachute journalism, quoting authorities or citing press releases issued by authorities or local newspapers, which are deeply committed to maintaining the status quo. Sensational and big stories are the only ones deemed important enough to cover, so the global narrative on these communities has produced intense prejudice, which further justifies societal stigma among elites who care about global perceptions of their city and depend on them for investment, in another vicious cycle.

Click here for Part 2.

This is the first article in a six-part series that comprises the chapter entitled “Not Everyone Has a Price: How the Small Favela of Vila Autódromo’s Fight Opened a Path to Olympic Resistance” recounting the story of Vila Autódromo’s struggle. The chapter is part of the book ‘Rio 2016: Olympic Myths, Hard Realities.’ RioOnWatch would like to thank Brookings Press for providing the permission to republish the chapter here in its entirety.

Notes

[a] Rio was the largest slave port in world history, and slaves constituted some 40 percent of the city’s population [earlier] in the nineteenth century7 [and] prior to Brazil abolishing slavery in 1888; it was the last nation in the Western hemisphere to do so.

[b] Prior to Lacerda, evictions had taken place during the first decade in the century when Francisco Pereira Passos was mayor and led major urban reform initiatives, but these took out tenement houses, which hastened the settlement of favelas.

[c] Such a narrative serves in maintaining low self- and community regard in the psyche of favelados.

Additional Bibliographic References

[1] Robert Neuwirth, Shadow Cities: A Billion Squatters, A New Urban World (New York: Routledge, 2006), p. 58.

[2] Bryan McCann, Hard Times in the Marvelous City: From Dictatorship to Democracy in the Favelas of Rio de Janeiro (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2014), p. 2.

[3] Janice Perlman, Favela: Four Decades of Living on the Edge in Rio de Janeiro (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2010), p. 333.

[4] Brodwyn Fischer, A Poverty of Rights: Citizenship and Inequality in Twentieth-Century Rio de Janeiro, (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008), p. 60.

[5] Bryan McCann, Hard Times in the Marvelous City: From Dictatorship to Democracy in the Favelas of Rio de Janeiro (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2014).

[6] Theresa Williamson, “Rio’s Favelas: The Power of Informal Urbanism,” in Perspecta 50, edited by M. McAllister and M. Sabbagh (MIT Press, 2017).

[7] Rosana Barbosa, Immigration and Xenophobia: Portuguese Immigrants in Early 19th Century Rio de Janeiro (Lanham, Md.: University Press of America, 2009).

Complete Series: Not Everyone Has a Price: The Story of Vila Autódromo’s Olympic Struggle

Part 1: (Re)Introducing Favelas

Part 2: Introducing Vila Autódromo

Part 3: Vila Autódromo’s Rise as a Symbol of Olympic Resistance (2010-2012) [VIDEO]

Part 4: Intimidation and the Critical Turning Point (2013-2014) [VIDEO]

Part 5: The City Proceeds with Eminent Domain and Violence (2014-2016) [VIDEO]

Part 6: Conclusion—Vila Autódromo in the Context of Rio’s Olympic Evictions

Also see: Timeline of Vila Autodromo

*RioOnWatch is a project of the NGO Catalytic Communities