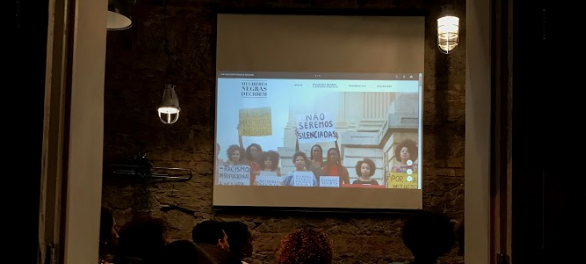

On Saturday, July 21, the digital platform Black Women Decide was launched by the Umunna Network. The platform aims to provide data in support of black women’s movements seeking greater representation in politics through electoral processes. The event took place at Olabi in Botafogo. At the event, Olabi director Silvia Bahia spoke about the importance of creating spaces for black women to organize. “There’s no room for the idea that black women are not interested in politics and technology. Umunna is proof that when black women shape the future, it really makes a difference.”

The Black Women Decide platform is divided into three main sections: Myths, Black Women and the Political System, and the Diagnosis. In the Myths section, the platform deconstructs myths about the presence of black women in political positions. Often, these myths have repercussions in society because a superficial view of certain facts can generate false ideas—which the platform seeks to combat with actual data. Below are some examples of myths countered on the platform.

One of the myths that the platform combats is that “black people do not vote for black candidates,” which consists of the idea that in Brazil it is white people that put black candidates in positions of power. According to the platform, the Electoral Courts don’t disaggregate the electorate by race, so it is impossible to generate a clear analysis that would link black voters to black or white candidates. Even so, according to the website, in analyzing the electoral maps of two black women politicians, Benedita da Silva and Marielle Franco, for example, it’s apparent that the candidates received votes in all electoral zones in the state and in the city of Rio de Janeiro, respectively. This is proof that black voters participated in electing these candidates. Sociologist Ana Carolina Lourenço, policy coordinator of the Umunna Network, said on the day of the launch that black candidates’ possible lack of reach may be due to the fact that white men’s campaigns are 31 times more highly funded than those of black people.

Another myth refuted by the platform is that “there is no relation between being a black woman and defending human rights.” According to the platform, the truth exposed through concrete data is that 70% of black women elected to the federal Congress in 2014 are affiliated with parties that defend human rights. “According to an evaluation by #MeRepresenta, the majority of black Congressmembers belong to a party with a classification between 90 and 100—those that are most aligned with human rights agendas,” the platform informs.

The myths that “there are few black women because they do not run for office” and that “black women, if elected, would only defend black women’s agendas” were also easily deconstructed. The platform states that the number of black female candidates is close to the number of white female candidates, yet data show that white women are 3.2 times more likely to be elected than black women. At the same time, the site states that the agendas of black candidates demonstrate that they are concerned with all sectors of the community and not only with other black women. “The traditional patterns of black women’s movements offer a universal and broad vision to combat problems in society.”

In the section “Black Women and the Political System,” a podcast was released with episodes from the “Black Women Decide” series. In the first episode, sociologist Ana Carolina Lourenço and statistician Juliana Marques talk about electoral rules, voting maps, and activism in the elections based on public figures Lélia Gonzalez, Benedita da Silva, Jurema Batista, and Marielle Franco. The episode explains moments in Brazilian politics that involved black candidates.

Through tables and visual data, the “Diagnosis” section shows characteristics of the lack of representation of black women in current politics, presenting suggestions for change. This section talks about investment in black women’s candidacies, which comprises only 2.51% of total investments of all candidates running for Congress. This number contributes to the chances that black women will be elected, which, as shown in the platform’s infographics, were only 1.6% in 2014. “In addition, the indicator appears zeroed for candidates with a lower level of education than a university degree—different from other demographic groups,” the platform reports.

All of the data exposed by the platform will bolster black women’s fights for greater political representation. The different sections of the platform clearly expose problems that need to be remedied, such as the lack of campaign funding. The demystification of false ideas is also very important for policy debates in which the lack of concrete data can affect the population’s perception of black candidates. As such, the Black Women Decide platform is an important tool to increase the representation of black women in the 2018 elections.