This is the eighth article in an ongoing series on the Brazilian electoral political scene in 2018.

The first of two rounds of voting for Brazil’s next president takes place this Sunday, October 7, when the field of candidates will narrow to the final two who will be voted on three weeks later, on October 27. In a nation where blacks comprise 55% of the population and black women comprise the single largest demographic of 27%, Brazil is choosing from 13 candidates, 11 white males and 2 black females. The latest polls put Bolsonaro in the lead in the first round at 32%; Haddad at 21%; Ciro at 11%; Alckmin at 9%; and Marina at 4%.

A word frequency analysis of the Brazilian presidential candidates’ government proposals reveals a relative absence of the word “favela.” Despite an increase in the use of the word “periphery” and its variations (six candidates mention the word, compared to only two in 2014), the word “favela” only appears in the plans of candidates Guilherme Boulos (eight times), Geraldo Alckmin (one time) and Fernando Haddad (one time). The word “community” appears three times with a similar meaning to “favela” in João Goulart Filho’s plan and likewise appears three times in Haddad’s plan and eleven times in Boulos’ plan. The low frequency (or even absence) of the word reveals the non-territorialization of the proposals—which are often vague and lack attention to the specific needs of favela residents, who represent one of Brazil’s most vulnerable populations and who correspond to a significant share of the Brazilian population (6% as of 2010) and even more so of its cities (in the case of Rio, 24%).

Below, see the proposals of each candidate that most directly relate to favelas and peripheries:

Geraldo Alckmin (Brazilian Social Democracy Party)

Alckmin’s 51-page Government Program proposal diagnoses that “the accelerated growth of urban peripheries leads to the combination of deficiencies in housing, sanitation, and mobility.” Thus, he proposes intersectoral policies to carry out land regularization of “settlements, clandestine occupations, and favelas” with the “support of the new law” (including the construction of “infrastructure, sanitation, and essential facilities”); to “expand sanitation coverage in urban peripheries” and subsidize the delivery of potable water and sewage treatment; to control the effects of natural disasters related to water and sanitation in cities; to improve and institutionalize the federal public housing program Minha Casa Minha Vida so that it is not a transient government policy; to promote public rent assistance for low-income families, as well as young and elderly people; to de-bureaucratize the licensing of social interest housing projects; to stimulate public-private partnerships and private investment to construct public housing; and to register families in need of housing and coordinate public housing policy for those in vulnerable economic, cultural, and social situations. He also proposes to “guarantee respect for property rights, whether public or private, with unequivocal land repossession policies” but at the same time “promote property rights through the regularization of housing and land occupied by disadvantaged populations”—which raises questions as to how families who do not hold land titles in favelas and occupations will be treated.

In the area of public security, he aims to combat organized crime and reduce the number of homicides, primarily those of youth. To this end, he proposes to invest in social protection and care for victims of gender-based and racial violence by expanding shelters and support networks and encouraging the Military Police and Municipal Guard to carry out “Maria da Penha” [anti-domestic violence] patrols. He also proposes to invest in conflict mediation by providing assistance to victims of fatal violence; in measures to prevent youth from engaging in crime; in intelligence actions at the borders and in prisons; in police training; in a national homicide-reduction program; in the integration of security systems and forces; in the creation of a federal military police force (the National Guard) to fight organized crime and agrarian conflicts; in the expansion of the role of the Municipal Guard in public security; in human rights education programs for public servants in the justice and public security systems; and in “awareness campaigns for crimes that inflict moral damages.” Additionally, he proposes to restrict prison sentence reduction; to deal more rigorously with adolescent repeat offenders; to include new offenses in the penal code; to build more prisons through public-private partnerships; to accompany former inmates with legal, psychosocial, and familial support and stimulate professional training programs; and “to guarantee the right for children and adolescents to live with mothers and fathers serving sentences in closed conditions.”

He also proposes the expansion of Bolsa Família and the Family Health Program; the eradication of extreme poverty (not only in terms of income, but also in terms of housing and nutritional status); the implementation of restaurants serving meals for R$1 (US25¢) in all capital cities; the creation of the National Observatory to Combat Racial Discrimination; the promotion of “black youth leadership”; the creation of a policy to combat violence against women and black youth; and the de-bureaucratization of public calls for cultural proposals and the promotion of local cultural events.

João Amoedo (New Party)

Amoedo’s 23-page plan entitled More Opportunities, Fewer Privileges recognizes that violence most significantly impacts peripheral youth. Amoedo’s proposals for security include the integration of police forces; the prioritization of public security and the valorization of police officers (including specific performance targets, bonuses, and career paths); investment in prevention and technology-based research; the restriction of reduced prison sentences; the imprisonment of repeat offenders; and the construction and management of prisons in partnership with the private sector.

Amoedo also proposes to universalize sanitation in Brazil (also in partnership with the private sector) and improve Bolsa Família and other social programs in order to benefit the poorest populations and enable their full citizenship. The proposal also foresees beneficiaries’ eventual exit from social assistance programs via the job market and professional training programs so that they have “opportunities for dignified work, entrepreneurship, and increased incomes without living in poverty and amid backwardness.”

Jair Bolsonaro (Social Liberal Party)

Bolsonaro’s 81-page Path of Prosperity plan (also called the “Phoenix Project”) focuses on fighting crime, corruption, and political patronage. He proposes to employ the Armed Forces in the fight against organized crime; to legally protect police officers who commit crimes while on duty (according to his plan, “only 2% of violent deaths in Brazil [are] associated with police actions”); to reduce the minimal age of criminal responsibility; to “arrest and keep those arrested imprisoned” (ending the sentence reduction provision for good behavior); and to allow the use of weapons (which may be used to kill or to save lives, according to him, depending on the nature of the person holding it) for self-defense and the defense of family members and property. The plan also proposes to classify the act of remaining on a given property without a land title—as frequently occurs in favelas—as an act of terrorism. Finally, the plan aims to improve the Bolsa Família program to create advantages for beneficiaries, but it is not clear how this would be achieved.

Guilherme Boulos (Socialism and Liberty Party)

Boulos’ 228-page ‘Let’s Change Brazil Without Fear’ Coalition Proposal recognizes that there is an “oppressive and repressive logic of extermination in urban peripheries against the poor, youth, black people, women, and the LGBTI community”—but that peripheries are also spaces of resistance. The plan also recognizes that the government is not absent in peripheries and favelas, but is rather present “almost exclusively through policies of control, surveillance, and repression.” In contrast, the government is completely absent with regards to “arts facilities, culture, sport, and leisure” and almost totally absent in terms of healthcare facilities and sanitation services.

As such, Boulos proposes to demilitarize the police—which includes the extension of labor rights to police officers and training to protect lives and promote human dignity; to valorize security professionals; to withdraw the Armed Forces from policing activities; to put an end to [extrajudicial executions in] “act of resistance“; to end the genocide of the black population; and to end the war on drugs—including a policy to redress damages caused by the violence of this war in peripheral communities and by the violence perpetrated against black and indigenous populations. Moreover, the plan promises to provide education for the prevention of drug use and gradual regulation of the sale of drugs; to control weapons and ammunition; to reconcile public safety with human rights; and to strengthen educational, leisure and income-generating opportunities as a strategy for violence prevention.

He seeks to enhance democracy in peripheries, which “still experience true states of exception—with home invasions without warrants, extrajudicial killings, torture in police stations, and illegal arrests.” The plan also proposes to create a new Truth Commission to investigate crimes committed by the government after the end of the dictatorship, including massacres and deaths as part of the genocide of the black population.

His proposals for urban policy are intersectoral and provide for democratic, participatory, and non-homogeneous urban planning and management processes. Among the proposals in this area are the “regularization of houses located in favelas and public housing developments”; the “upgrading of favelas to guarantee quality of life and infrastructure”; the construction of housing units according to local needs and contexts (including construction by self-managed cooperatives on public properties owned by the federal government); the universalization of the water supply (with priority for “rural areas and some favelas in large cities”) and sewage services with reduced social tariffs for poor families; the promotion of the social function of property; the “expropriation and acquisition of land for social interest housing”; policies for rent assistance and social hotels [for the homeless]; public technical assistance; the titling of quilombo communities, including those in urban areas; and the fight against environmental racism (as observed in the environmental risk discourse used to justify evictions). He also proposes the Guaranteed Employment Program, through which the government would compensate the workforce for the construction of social infrastructure such as public facilities (squares, sports fields, nurseries) in peripheries; basic sanitation infrastructure; and the redevelopment of urban space.

Boulos proposes to promote black and peripheral cultures “through de-bureaucratized public calls for proposals”; to expand access to cultural goods and facilities; and to invest in the “occupation of territories with cultural and economic production”—including de-bureaucratizing cultural events in public spaces. He proposes to strengthen community media vis-à-vis major media outlets by promoting community television and citizenship channels, restoring the Free Media Centers program, creating policies for local community-based journalism at public facilities such as schools and cultural centers, and including media education courses in schools.

He also proposes to maintain affirmative action programs in access to higher education, coupled with retention policies; to create quotas in the representative political system and in hiring for public sector jobs; to implement policies that promote job opportunities with respect for gender-based and racial equity criteria; and to raise the value of the welfare assistance program Bolsa Família, transforming it into a Universal Basic Income (UBI) program; to guarantee the instruction of Afro-Brazilian history in schools; and to implement the National Policy for the Integral Health of the Black Population.

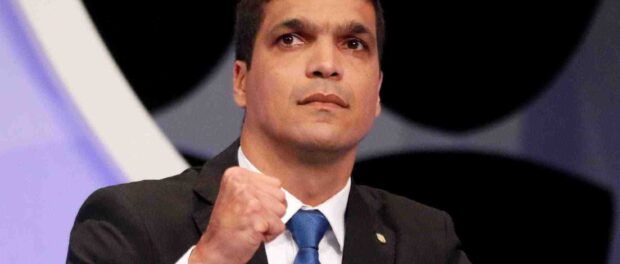

Cabo Daciolo (Patriot)

Daciolo’s 17-page National Plan for the Brazilian Colony is marked by references to Christianity and the exaltation of the Armed Forces. In terms of public security, the plan proposes to prevent and combat drug trafficking, which will include an effective increase in police and the Armed Forces and the allocation of 10% of GDP for security. The plan does not contain any specific proposals for housing, urban upgrading, or culture.

Álvaro Dias (Podemos)

Dias’ 15-page Plan of 19+1 Goals to Rebuild the Republic is characterized by several proposed tax cuts and economic growth proposals focused on the agribusiness sector. The goals with the greatest potential to impact favela residents are those relating to public security and urban and rural property titling. With regard to public security, Dias proposes to invest in police, fostering the integration of police forces and promoting intelligence actions to reduce homicides and robberies. In relation to titling, his goal is to issue five million new titles by the end of the presidential term. In the area of culture, he proposes to reform the Culture Pass to enable low-income populations to access cultural goods and facilities.

José Maria Eymael (Christian Democracy)

Eymel’s 9-page Charter 27: General Governance Directives to Build a New and Better Brazil includes a guideline concerning public security with proposals to integrate security forces, strengthen borders, and overhaul the prison system in order to place more emphasis on the resocialization of former inmates. There is also a guideline to guarantee the social right to housing, which includes public policies and the improvement of government programs that ensure dignified housing and respect the social function of housing such that “absence of income does not represent the absence of housing.”

Ciro Gomes (Democratic Labor Party)

Gomes’ 62-page plan entitled National Development Strategy Directives for Brazil focuses on economic development and overcoming the economic crisis with the goal of “protecting the poorest, improving the well-being of the population, and accelerating the process of income distribution,” among other objectives. An example of such a proposal is the provision of de-bureaucratized and inexpensive credit “to reform and expand housing for low-income families” in order to simultaneously improve the living conditions of these families and revitalize the labor market through civil construction work. Gomes’ plan also foresees the universalization of water supply and sewage collection and treatment services, as well as the reinforcement of the Minha Casa Minha Vida program in terms of resources, infrastructure, and services in surrounding areas (transportation, healthcare, and education).

In the area of public security, he proposes an increase in the share of GDP allocated to the Armed Forces; improvements to working conditions for police; and a focus on investigative intelligence, in addition to the creation of a Border Police force to prevent the entry of weapons and drugs into the country. He also proposes policies to fight police violence, “seeking the preservation of the lives and citizenship of black youth;” prevention policies based on “the creation of a system to monitor formerly incarcerated young people; and the inclusion of youth [who reside] in areas of conflict and homeless people in vocational programs.”

In the area of culture, he wants to popularize access to culture and leisure, especially in the peripheries, and to stimulate “cultural manifestations conducive to social inclusion and peripheral street culture such as dances, graffiti, and slams” and “demonstrations and [the] dissemination of Afro-Brazilian culture.”

João Goulart Filho (Free Fatherland Party)

Goulart’s 14-page plan to Distribute Income, Overcome the Crisis, and Develop Brazil proposes urban reforms centered on the provision of housing for all, which includes the occupation of vacant properties through progressive taxation, the construction of new public housing, and land titling in favelas. The plan envisions the universalization of access to potable water and a goal to achieve 80% access to sanitation services.

He believes that the primary cause of violence lies in social inequality and that the best way to prevent violence is through security—by way of government presence in favelas and peripheral areas, “providing work, education, healthcare, and leisure for youth.” He proposes to achieve this through a Unified Public Security System “to address organized crime in prisons, at the border, and in communities” and by resocializing formerly incarcerated individuals, as well as facilitating the creation of Community Safety Councils (independent from the government) to foster popular participation in this process.

Finally, he proposes a policy to dismantle barriers for “Brazilians of African descent,” including [proposals to] combat racism, [uphold] affirmative action policies [to enable] access to education and culture, to [promote] religious tolerance, and to [provide] specific health care services.

Fernando Haddad (Workers’ Party)

Haddad’s 61-page Government Plan 2019–2022 recognizes that “the logic of the reproduction of inequalities” has not yet changed in urban spaces. The socio-territorial manifestations of these inequalities lie in infrastructure deficits and in the “segregation represented by favelas and peripheral housing.” Thus, he proposes an urban policy that articulates territorial planning, the regularization of “irregular land lots and precarious settlements” (which will include the revision of Law 13.465/2017 and a new national land regularization policy), housing, urban mobility, environmental agendas, and agendas to combat violence and racial and gender-based inequalities. He plans to develop such policies in accordance with the City Statue, New Urban Agenda, and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

Specifically for housing, Haddad proposes policies that include public rent assistance and measures to combat real estate speculation and fulfill the social function of property mandated in Brazil’s Constitution; the production of new housing units of social interest, especially in central areas (via location subsidies); and popular technical assistance and the redevelopment of underutilized buildings. He also proposes to reinstate the Growth Acceleration Program (PAC) for the Upgrading of Informal Settlements, which would include the implementation of infrastructure, elimination of risk, environmental recovery, and the guarantee of residents’ right to permanence and ownership. He also proposes to renew the Minha Casa Minha Vida federal housing program in areas located closer to consolidated infrastructure works and jobs in a way that prioritizes families in the lowest income group (with a total family monthly income up to R$1800 or US$450). He also proposes to stimulate environmental technologies (such as solar energy and water reuse) to strengthen [the federally funded, self-managed housing cooperatives program] MCMV Entidades in a participatory manner.

In terms of public security, he proposes a “national pact for the elaboration and implementation of the National Plan to Reduce the Mortality of Black and Peripheral Youth”—placing the reduction of violent deaths as the priority of a citizen security program. This public security program will be based on intersectoral policies that promote the “quality of public services in vulnerable territories and draw attention to the situation of children, young people, black people, women, and the LGBTI+ population, with priority for black youth living in the peripheries.” Furthermore, his proposal is based on the “renegotiation of relations between police and communities”; police investigations to clarify crimes of homicide and robbery; gun and ammunition control policies, including at the borders; and intelligence to remove weapons from circulation and reduce domestic and international trafficking to fight against armed groups in “vulnerable territories and communities.” Additionally, he proposes to reform and demilitarize police forces and value security professionals; to fight against torture; to put an end to “acts of resistance [followed by death]”; and to provide employment, income-generating, educational and cultural [opportunities] as alternatives to illegal markets and violence.

Specifically with regard to drug policy, he proposes to overcome the paradigm of the war on drugs and combat drug trafficking through the Federal Police—focusing on prevention through education on the use of illicit drugs, the promotion of “social and development policies in communities that are currently criminalized,” and the transformation of the drug problem into a public health issue. In order to achieve this latter point, he proposes to “strengthen the psychosocial care network, pass harm reduction policies, and act sensitively to address different and flexible forms of prevention in relation to diverse social groups.

In the area of education, he proposes an agreement with states in order to “hold the federal government responsible for the schools located in regions of high vulnerability”—that is, those with “high levels of violence (especially against black youth)” and low school performance. The agreement will include a pedagogical project based on the recognition of knowledge; school renovations; the provision of Internet access; the implementation of laboratories, libraries, and facilities for sports and cultural activities, as well as scholarships for low-income youth; and the transformation of schools into cultural and recreational centers for surrounding communities. In the area of employment, his plan will provide technical training in entrepreneurship as a way to combat inequality, especially for youth and women from the peripheries—who “are the fastest growing [demographic] of small business owners and who need to prepare themselves to develop their companies and transform their lives and communities.”

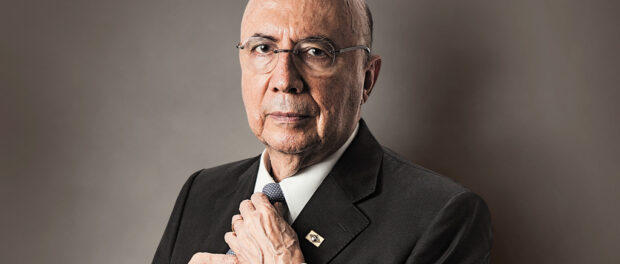

Henrique Meirelles (Brazilian Democratic Movement)

Meirelles’ 21-page “Pact for Trust!” focuses on attracting investment to Brazil and developing infrastructure—prioritizing public works of basic sanitation, urban transport, and nurseries. The plan recognizes and considers the mortality rate of black youth to be unacceptable. In terms of public security, Meirelles proposes increasing police street patrols, increasing public-private partnerships, and investing in research and intelligence. The plan does not contain any specific goals for public housing or peripheral culture.

Vera Lúcia Salgado (United Socialist Workers’ Party)

Salgado’s proposal entitled a “16-Point Socialist Plan for Brazil in Response to the Capitalist Crisis” includes three specific references to the periphery, all related to black youth who are experiencing genocide. She advocates for the “fight against racism and the myth of racial democracy,” calling for “historical reparations, an end to the overexploitation and genocide of poor black youth, and an end to social inequalities between black people and white people.” In terms of public security, she proposes demilitarizing the police—in the form of a publically accountable unified civilian police force with the right to organize and form unions—and the decriminalization of drugs, such to place production and distribution under government control, treat drug dependence through the public health system, and eliminate drug trafficking and justifications for “killing and imprisoning black youth.”

She proposes that education, healthcare, and housing should be considered rights and not commodities through the nationalization of schools, universities, and private hospitals. She also proposes the expropriation of vacant properties for affordable housing; land regularization; the construction of public housing; and an end to evictions. Furthermore, her plan proposes to decriminalize poverty and peripheral social struggles, which she claims is occurring through anti-terrorism and drug laws and through the federal military intervention—which, according to her plan, is “an attack on the city’s poor population with the aim of further repressing poor people and avoiding social rebellion.” Her plan also proposes to create self-managed popular councils in neighborhoods, factories, workplaces, and schools to decide on resource allocation so that workers and the poor participate in politics every day and not only at the time of voting.

Marina Silva (Sustainability Network)

Silva’s 24-page plan for A Fair, Ethical, Prosperous and Sustainable Brazil treats public safety as a social security problem and not just a policing problem, proposing an integrated policy that includes education, healthcare, sports, and culture with a focus on valuing life, preventing violence, and generating opportunities for youth. She also proposes integration between security forces, intelligence actions, and violence prevention policies in order to specifically combat the “high homicide rates of black youth in Brazil” and “hate crimes linked to racism.” She furthermore proposes a policy of valuing black culture.

She proposes to create a network of Family Development Agents who will conduct home visits to the most vulnerable families—updating the Unified Registry; creating a Family Development Plan; and providing the government with information about the deficiencies, opportunities, and effectiveness of social programs. The objective is to “offer these families and all Brazilians in vulnerable situations job opportunities and the necessary conditions to meet their basic needs in an independent way, through referral to vocational training services, access to microcredit in order to run small businesses, and quality public and community services that contribute to the well-being of all.” In addition, she will maintain the Bolsa Família program and examine the possibility of implementing a Universal Basic Income program.

Silva also commits to “policies for integrated urban planning in cities and metropolitan areas, which, in addition to the right to housing, guarantee access to public transit, waste collection, basic sanitation, and quality public services” in order to reduce inequalities. In addition, her plan provides for the strengthening of public housing programs, primarily through public rental properties combined with upgrading abandoned or underutilized buildings in city centers, which could create more compact cities and promote greater coexistence among social classes.

This is the eighth article in an ongoing series on the Brazilian electoral political scene in 2018.