Brazil is among the 30 countries with the highest rates of gun ownership in the world—and this is only counting legal firearms. Brazil, thus, is already an armed country. Those who are from favelas know this well—and they also know that this situation has not led us to any state of peace. According to statistics from the Global Mortality from Firearms study, Brazil is the country with the highest number of firearm-related deaths. The firearm-related homicide rate is even higher than that of the United States, the country with the highest rate of gun ownership.

Even so, in the last week of campaigning for the first round of elections, presidential frontrunner Jair Bolsonaro of the Social Liberal Party (PSL) vehemently defended arming more people. For him, guns are the guarantee of freedom for the population. However, this is not what the favela population believes. Amidst the gun violence epidemic, police and criminals alike are killed, in addition to many innocent bystanders—victims of “lost” bullets that find the bodies of favela residents.

On September 17, 26-year-old Rodrigo Alexandre da Silva Serrano was killed by police. According to community residents, the Military Police mistook his umbrella for a gun. Serrano, killed in the favela of Chapéu-Mangueira, in the South Zone of Rio de Janeiro, leaves behind two small children and his wife.

Last Monday, October 2, 17-year-old teenager Anderson Cardoso was shot and killed in Complexo do Alemão, in the North Zone of Rio de Janeiro. According to testimonies, the young man was mistaken for a criminal in his own home.

Present at the large #EleNão (#NotHim) protest—organized via social networks by the group Women United Against Bolsonaro—which took place in downtown Rio on September 29, Maré resident Bruna Silva stated that “his politics are precisely what I want to combat: extermination in favelas.”

The extermination that Silva refers to is the conflation of any favela resident’s body with criminality. This logic, that criminals ought to die—also upheld by the PSL’s presidential candidate—threatens innocent lives. These killings affected her directly: her son, Marcos Vinícius, who was only 14 years old, was killed in Complexo da Maré on June 20 as he returned home from school—due to canceled classes from a police operation—wearing a school uniform and carrying his school supplies. “The favela [is marked by a] stigma that we are criminals,” Silva explains.

#NotHim Also Reaches Favelas

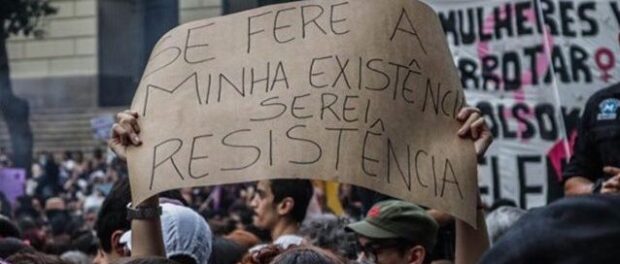

Women, LGBT persons, Christians, Afro-Brazilian religious practitioners, students, teachers, favela residents, and people of many groups who oppose Bolsonaro took to the streets across the country on September 29. The movement, which was born on social media, drew more than 200,000 people to the streets in Rio de Janeiro alone, in addition to other demonstrators throughout Brazil and around the world.

Favela residents were among those who organized and took to the streets in Rio de Janeiro. On social networks, they have placed themselves on the front lines in combating the prejudiced and stigmatizing statements of the presidential candidate who leads the first-round voting polls.

Filipe dos Anjos, Secretary General of the Federation of Favelas of the State of Rio de Janeiro (FAFERJ), recounted: “We created a Facebook event by FAFERJ, but we knew that [the protest] would be led by women. We, favela residents, were present.” According to Anjos: “The problem of Bolsonaro is the rise of fascism. We are in a period of crisis with regards to public security and the economy [with] a high unemployment rate. History tells us that it is in these conditions that fascism resurges in society, with increasing strength. The rise of Bolsonaro has brought forth all types of prejudice in society.”

With regards to favelas, Anjos cautioned: “The danger of Bolsonaro, for favelas, is that a portion of society—such as the bourgeoisie—sees the favela as the enemy and treats favelas as territories of conflict and backwardness. Society designates favelas as sites for combating serious problems with arms and force. We know that the favela is a solution. We represent a third of Rio, and the majority [of residents] are workers. The danger of Bolsonaro is the further upsurge of [violence] against favela residents.”

According to O Globo, in February of this year at a finance conference, Bolsonaro said that police could gun down Rio’s largest favela, Rocinha if criminals did not turn themselves in. “It is an extremely prejudiced statement, suggesting that there are only criminals in favelas. In reality, there are many criminals by his side over there in Brasília. Favela residents are workers,” declared activist Cosme Felippsen, who is a resident of Morro da Providência, a tour guide, and founder of Rolé dos Favelados.

Demonstrators Crowd the Streets of Rio

Last weekend’s demonstration was very powerful and immense. Protestors walked from Cinelândia to Praça XV. Upon arrival, there was a stage where many speeches were given, including by a group of mothers who organize in collectives to protest against violence and advocate for human rights.

“It has not ended. It must end. I want an end to the Military Police,” shouted women holding banners with the faces of the victims of state violence—the majority of whom are black youth. In a powerful scene, Bruna Silva held the iconic blood-stained shirt of her son, Marcos Vinicius.

“We are here. We may seem to be a small group, but sadly there are huge numbers of us, and we are truly the sentiments that we are shouting today. Not him! Never him! Never him. We do not want to lose anyone else. Enough of black people being battered and murdered. Enough! We do not want more. We are the families that this government kills and maims. Black lives matter!” yelled protestor Mônica Cunha through a microphone. Cunha is a member of the Movimento Moleque and the mother of a victim of state violence.

Brazil and God

Cosme Felippsen is Christian and criticizes what Bolsonaro has to say about religion. “From the perspective of a genuine Christian, Bolsonaro is not Christian… Many people call themselves Christian when they have a microphone in their hand, in the media, with cameras watching. But they are in a place of evil, they are preaching anti-Christianity. Jesus Christ would not advocate for even 1% of what this person says,” said Felippsen.

Felippsen also spoke about favela residents who support Bolsonaro, his expectations for the election, and his views. “It is sad to see favela residents increasingly discouraged and distrustful. I have a friend—a black woman, who lives in a favela—who supports Bolsonaro because she says that he is the only one who can combat corrupt politicians. I still have hope for the elections—not much—but I still believe that we must continue to organize. I don’t fear the words of bad [people], but rather the silence of good [people]. Favela residents who don’t support him need to take a stand,” Felippsen concluded.

Rithyele Dantas is a journalism student from Morro da Cruz in Andaraí. Dantas is a photojournalist and has worked as a community educator and parliamentary assistant in Rio. She is also the founder of the blog Jornalistas Pretas, a project that she believes to be important in guaranteeing human rights.