Brazilians voting in the presidential run-off election tomorrow, Sunday, October 28 are presented with a choice between two candidates with very different policies on housing and upgrading in favelas and security for favela residents. The candidates’ differing ideologies are reflected in their distinct approaches to favelas. While Fernando Haddad (Worker’s Party–PT) visited Rocinha and Maré during the campaign, Jair Bolsonaro (Social Liberal Party–PSL) visited the Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) in City of God and the Special Operations Battalion (BOPE) headquarters in Tavares Bastos, speaking with police officers who work in favelas but not with residents themselves.

Learn more about the candidates’ positions and policies regarding favelas:

Fernando Haddad (Workers’ Party–PT)

1. Valuing Life

During their visit to Complexo da Maré, Haddad’s running mate Manuela D’Ávila (PCdoB) said that the second round of the election “is about democracy—but for people living in peripheries and favelas, it’s about life.” Haddad and D’Ávila were invited to speak alongside two mothers who have lost their sons to police violence. One of the mothers was Bruna Silva, mother of Marcos Vinícius—the boy killed by a police officer while wearing his school uniform on the way home after his school was closed due to a police operation. “He was on the right path, in the right place, at the right time,” said Silva. D’Ávila and Haddad positioned themselves on “the side of life,” in opposition to their opponent. Later that day, Haddad noted that it’s necessary for Brazilian left-wing politicians to look to the peripheries and return to local organizing.

2. Ending ‘Acts of Resistance Followed by Death’ by Police and Reducing the Mortality of Black Youth from the Peripheries

Haddad proposes a citizen-led public security model with policies that guarantee that government not only enter favelas by way of force; that promote “the renegotiation of police-community relations;” that “call attention to the situation of children, youth, black people, women, and the LGBTI+ population—with priority for black youth who live in the peripheries” with the aim of ending autos de resistência (police killings registered as “acts of resistance followed by death”) and keeping black youth alive. To this end, he aims to implement a National Plan to Reduce the Mortality of Black and Peripheral Youth; to focus on investigations and police intelligence to fight drug trafficking; to implement a policy to control the sale of arms; to withdraw the Armed Forces from favelas; and to demilitarize police, while continuing to value public security agents. He promises to invest in job creation and the provision of education and culture as alternatives to crime and violence.

3. Regularizing Land Tenure and Combating Real Estate Speculation

Haddad plans to fight real estate speculation and guarantee the fulfillment of the social function of property as held by Brazil’s Constitution. He will invest in public rent assistance; in the production of new social housing, especially in central areas; in the repurposing of under-utilized buildings; and in community-based technical support for construction projects. He also supports the revision of Law 13.465/2017 and a new national land regularization policy. During a meeting with the Archbishop of Rio de Janeiro and the Pastoral de Favelas (on the same day of his visit to Maré favela), Haddad formalized his commitment to land regularization—a central focus of the Pastoral de Favelas.

On a visit to Rocinha during the first round of campaigning, Haddad also announced his intention to renew the Growth Acceleration Program (PAC)—Upgrading of Precarious Settlements (creating infrastructure, eliminating risks, protecting the environment, and guaranteeing residents’ permanence and land tenure). According to Haddad, resuming infrastructure projects—many of which were abandoned after the Olympic Games—is also an answer to problems of unemployment and violence in vulnerable areas. Haddad’s government plan also proposes to invest in the Minha Casa Minha Vida public housing program in locations near consolidated infrastructure and employment opportunities, addressing one of the program’s major criticisms, and strengthening the cooperatively-managed Minha Casa Minha Vida—Entidades program.

4. Allocating Specific Funds for the Culture of the Periphery

During his visit to the Maré Arts Center, Haddad recognized that important forms of cultural expression were born in favelas, including samba, hip-hop, and funk. He promised to replicate a program that he initiated as mayor of São Paulo, the Program for the Promotion of Culture of the Periphery, to democratize access and allocate specific funds from the Ministry of Culture to support cultural projects in vulnerable areas.

5. Providing Retention Scholarships and Transforming Schools in Favelas into Laboratories and Cultural Hubs

Haddad proposes to create an agreement between the federal government and state governments to grant the federal government responsibility for schools located in highly vulnerable areas—i.e., areas “with high levels of violence, especially against black youth” and low levels of investment in education. This agreement would include projects to remodel the physical structures of schools (with the construction of laboratories, libraries, and cultural and sports facilities). The proposal also includes funding for retention scholarships for high school students living in poverty and the transformation of schools into cultural and recreation hubs for surrounding communities.

6. Ending the War on Drugs

Haddad proposes to overcome the paradigm of the “war on drugs” and focus on prevention through education and “social policies to develop communities that are currently criminalized.” He also proposes to fight drug trafficking via the Federal Police and transform drug policy into a public health issue (including psychosocial care and harm reduction policies).

Jair Bolsonaro (Social Liberal Party–PSL)

1. Granting Police License to Kill

In his government plan, Bolsonaro states that “only 2% of violent deaths in Brazil are associated with police actions” but that he wants to guarantee that assassinations and other crimes committed by on-duty police are not tried—not even by military courts—such as to legally protect them from the consequences of their actions. “If Bolsonaro wins, you can get the bodybags ready because there will be lots of innocent people to fill them,” predicted Bruna Silva, mother of Marcos Vinícius.

2. Criminalizing Untitled Land Occupations

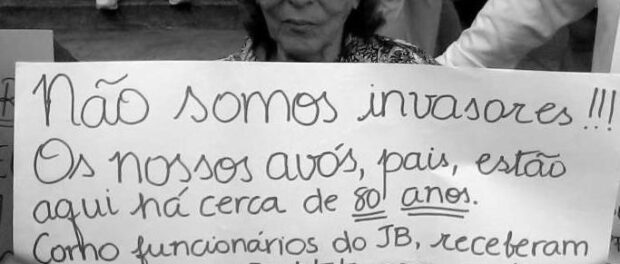

Bolsonaro pushes back against land regularization and land titling policies, proposing in his government plan that any person residing on land for which they do not hold title should be considered a terrorist (which is frequently the case in favelas, since despite constitutionally-granted squatters’ rights they rarely hold physical title). Furthermore, his plan envisions the repeal of “any relativization of private property in the Constitution—for example, the restrictions in Constitutional Amendment 81.” The constitutional amendment to which he refers allows for the expropriation of land used for slave labor or drug plantations for the purpose of agrarian reform or social housing. Repealing this amendment reinforces Bolsonaro’s commitment to land as private property—regardless of its purpose—and disregard for the social function of property as guaranteed by the City Statue. His plan does not mention housing or upgrading.

3. Implementing Distance Education and Restricting Access to Higher Education

Bolsonaro’s main educational policy proposal is distance education for elementary through high school education, with students only attending school for practice-based classes and exams. Beyond diminishing the quality of teaching, this policy goes against the idea of school as more than just a space for formal education but also a space for socialization and a space for children to spend their time. When at-risk children spend a great deal of time at home, chances increase of becoming involved in activities such as drug trafficking. Schools also play a role in social protection, identifying children who are experiencing violence at home. And children at home present yet another burden for working families who don’t have childcare options, beyond presenting a financial burden given the importance of school meals for child nutrition.

Another plan indicated by Bolsonaro’s team with regard to education is the introduction of tuition fees at public universities, which would reduce access to university for those who cannot afford the fees. This policy goes against affirmative action policies that aim to democratize access to higher education. Bolsonaro has spoken against affirmative action quotas in university admissions because, in his opinion, they reinforce divisions between people and what he mocks the “poor little victims” of women, gay people, black people, and people from Brazil’s Northeast.

4. “The Captains Will Be in Charge of Brazil”

Not only does Bolsonaro intend to use the Armed Forces to combat organized and urban crime—which has recently been the case in Rio de Janeiro, leading to a rise in deaths—but he also plans to place soldiers in positions of political power, creating an administration with “loads of military men running ministries,” in his words. During a visit to the Special Operations Battalion (BOPE) in Tavares Bastos favela in Rio de Janeiro, he declared that “the captains are going to be in charge of Brazil.” He shouted ‘Caveira’—a controversial battle cry used by BOPE officers. Bolsonaro’s visit to the BOPE headquarters was questioned as a possible electoral crime, given that the law prohibits political campaigning in public buildings.

In addition to being a former Army captain himself, alongside his running mate General Hamilton Mourão, Bolsonaro has already confirmed that he would appoint retired general Augusto Heleno to the Ministry of Defense. (Current interim president Michel Temer was the first president to appoint a military officer to the Ministry of Defense since its creation in 1999.) Bolsonaro has also shown interest in appointing retired Air Force lieutenant-colonel Marcos Pontes to the Ministry of Science and Technology. “I plan to have fifteen ministers. One must be a man, the Minister of Defense—a military general. The rest can all be women, gay, or afro-descendants,” he said in an interview with CBN.

5. Prioritizing the Police Rather than Residents

Bolsonaro visited favelas twice during his campaign. The first visit was in February before the campaign officially began, in City of God—where he visited the Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) base and posed for photos in front of a tank. On the same day, hours after Bolsonaro’s visit, 19-year-old Natacha Aparecida Cruz was hit by a stray bullet during a shootout between Military Police officers and drug traffickers. Bolsonaro’s second favela visit was during the second round of campaigning when he visited the BOPE headquarters in Tavares Bastos. Tellingly, on both visits, he had contact with police but not with local residents.

6. Authorizing Firearm Possession

In Brazil current law prohibits bearing of arms by all except security personnel. Bolsonaro supports authorizing the broad use of firearms in self-defense and in defense of family members or property. He believes that guns can be used to kill people or to save lives, depending on the character of the person in possession of the gun.