WhatsApp, the Facebook-owned messaging application, was once seen as a simple means of communicating and sharing information with friends and family. Brazil’s elections, however, showed precisely how as disinformation runs rampant and even family group chats become political minefields, a much more sinister narrative of what the platform ‘offers’ is taking form.

In a result seen by many as impossible without the rise of social media and WhatsApp as a political news source, Brazilians decisively elected far-right nationalist Jair Bolsonaro (Social Liberal Party–PSL)—previously a little-known congressman from Rio de Janeiro with almost zero official public advertising time—over Workers’ Party (PT) candidate Fernando Haddad on Sunday, October 28. A significant chunk of this is due to the rise of WhatsApp as a theoretically democratic (albeit unregulated) space to share information, posing a direct challenge to the heavily controlled primacy of television, radio, and print—a trend that seems unlikely to be reversed. Bad actors—with the help of unsuspecting users—subverted democracy through the mass, coordinated spread of lies via the unsuspecting platform.

What makes WhatsApp such a vector for disinformation?

Used by nearly seven out of ten Brazilians and 95% of all smartphone owners in the country, WhatsApp is ubiquitous. On top of everyday conversation, users share stories and memes with friends, family, and others in private or group conversations. Information received from such intimate sources can feel deceptively trustworthy, but the true source of information received via WhatsApp is extremely difficult to trace.

Beyond its tremendous popularity as a relatively no-frills messaging platform, WhatsApp sells its users on secure encryption and privacy. Unlike a public forum like Facebook, which can monitor public information (and sometimes, private information), WhatsApp has limited latitude to regulate usage without infringing on user privacy.

The burden of fact-checking rests on the shoulders of users—a heavy lift in a country where over half of the voting population has not completed high school and many are very new to social media. However, the issue is not only digital illiteracy but also a lack of access to legitimate methods of verifying information. Critically, through a partnership with Facebook, many cell phone plans in Brazil (particularly on cheap pre-paid phones) do not include data but grant users exclusive access to WhatsApp and Facebook as the sole entry points to the Internet. This reinforces the primacy of the two platforms as sources of information and obstructs users from consulting other sources in real time to check facts.

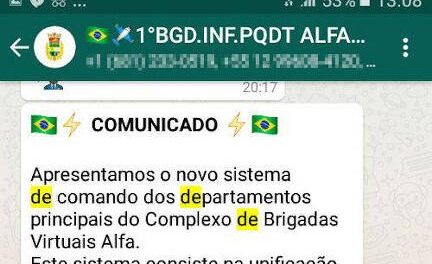

Key functionalities of the application itself, such as its group creation and forwarding functions, also make it possible to reach hundreds or even thousands of people with just a few taps. Groups in particular—both political and otherwise—are often echo chambers that reinforce existing views, stamp out dissenting thought, and actively work to delegitimize mainstream journalism.

What were some of the false stories being spread on WhatsApp?

Fake stories and conspiracy theories targeted both candidates. Most of the stories targeting Haddad involved communist fear-mongering (emphasizing or falsifying ties to Cuba and Venezuela) and claims that the Workers’ Party wanted to sexualize children, in an attempt to rally Brazil’s increasingly powerful evangelical lobby. False stories targeting Bolsonaro tended to be conspiracy theories about his health. However, only Haddad was the target of an orchestrated mass disinformation campaign.

Some of the most widely-disseminated false or misleading stories include:

- A story that Haddad wrote a book defending sexual relations between parents and their children (zero evidence of this)

- A story that Bolsonaro faked his near-fatal stabbing attack to win support (zero evidence of this)

- A story about a “gay kit” that the Workers’ Party would distribute to six-year-old children (this rumor has roots in a real educational program on LGBT rights known as “Schools without Homophobia,” which was ultimately vetoed by former Workers’ Party President Dilma Rousseff after pushback from evangelicals)

- A photo of an adult Rousseff with Fidel Castro (the photo of Castro is from 1959; at the time, Rousseff was only eleven years old)

- A tweet that Bolsonaro was secretly diagnosed with cancer and is not in sufficient health to finish a term (no evidence of this)

Where does fake news on WhatsApp come from?

Just over a week before the election, Folha de São Paulo exposed a scheme known as Caixa 2 (electoral slush fund), in which companies purchased millions of dollars’ worth of anti-Workers’ Party “fake news” for mass distribution on WhatsApp. The Caixa 2 is just one piece of the puzzle confirming suspicions that significant amounts of disinformation were orchestrated and not simply the product of organic political discussion. This scheme violated Brazilian electoral rules for at least three reasons: corporations are barred from making political donations, all electoral spending must be declared to regulators, and purchasing lists of phone numbers to spread content is illegal.

After joining and observing multiple pro-Bolsonaro WhatsApp groups for months leading up to the elections, David Nemer, an assistant professor at the University of Kentucky’s School of Information Science, observed that the actual creation of disinformation comes from a very small subset of “influencers” that are not technically associated with any campaign. Nemer approximates that only about 5% of members in these groups actually create content—the rest simply absorb content or actively reinforce it. Furthermore, Professor Viktor Chagas, a researcher at the Fluminense Federal University (UFF), found that phone numbers from Saudi Arabia, India, Pakistan, the U.S., Portugal, and other foreign countries are particularly motivated propagandists. “These numbers are a minority, but they are characterized by intense activity,” explained Chagas.

How did WhatsApp actually influence the outcome of the first and second rounds?

The true magnitude of WhatsApp’s impact on the election—due to information both legitimate and fake—is difficult to discern and will be studied for years to come. However, the consensus among experts and observers is that it was of significant influence and that Bolsonaro’s campaign benefitted far more than any other candidate.

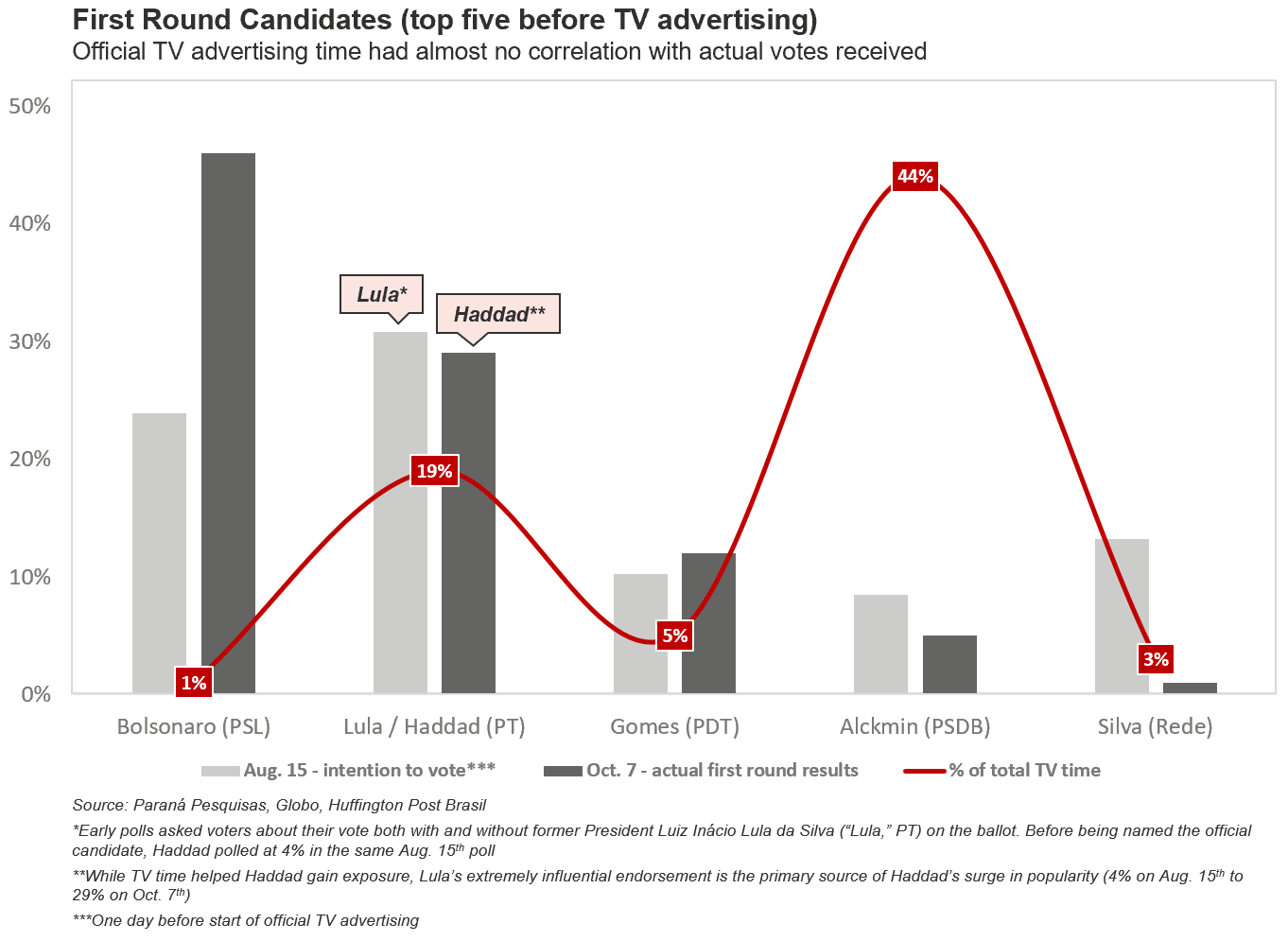

In the early running, it was difficult to even imagine Bolsonaro’s viability as a candidate due to his limited traditional media access. Social media skeptics and many analysts felt that Bolsonaro would be hobbled due to a lack of traditional, publicly regulated TV advertising against establishment heavyweights like Geraldo Alckmin (Brazilian Social Democracy Party–PSDB) or even Haddad, bolstered by the powerful backing of the Workers’ Party. In the first round, Bolsonaro received only 1%, or eight seconds, of fixed TV advertising time—historically, a death sentence. On the back of a voter coalition that was almost twice as likely to read news on WhatsApp than Haddad’s voters, Bolsonaro proceeded to win 46% of the first-round vote (Haddad, in second place, won 29% of the vote with 19% of fixed TV advertising time).

While fake and misleading propaganda was spread about both candidates, Bolsonaro was the prime beneficiary. In the Caixa 2 scandal, companies illegally spent millions of dollars to support Bolsonaro through WhatsApp—no such schemes supporting other candidates have been uncovered. “[Bolsonaro] monopolizes the debates in the majority of the 272 groups we’ve analyzed,” said Fabrício Benevenuto, a professor and founder of Eleições Sem Fake (“Elections Without Fake News”), a disinformation watchdog project. “He’s the protagonist in most of the news, videos, and memes circulating on [WhatsApp].” One study conducted by researchers at the University of São Paulo (USP), the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), and the fact-checking agency Agência Lupa concluded that more than half of the most popular memes on WhatsApp were either fake or misleading.

How has WhatsApp reacted to the misuse of its platform?

In August, WhatsApp reduced the maximum number of recipients of a forwarded message from 250 to twenty (this could be twenty individuals, twenty groups, or any combination). This was not a Brazil-specific change, but part of a global policy change following a wave of mob-lynchings in India—leaving at least 25 murdered—motivated by false rumors spread on WhatsApp.

In the wake of exposing the Caixa 2 scheme, WhatsApp pledged to work with authorities and both candidates to limit the proliferation of disinformation. Indeed, the service banned over 100,000 accounts, including that of Bolsonaro’s son and Rio Senator Flavio Bolsonaro (PSL) for spreading mass messages. However, WhatsApp repeatedly stated that additional restrictions, such as limiting the size of new groups or further limiting the number of recipients of forwarded messages, is “technically impossible.” WhatsApp has also expressed grave concerns about making any changes to the platform that would infringe on user privacy or freedom of speech, such as the monitoring of content in personal or group messages.

Critics have derided WhatsApp’s response as passive and too little, too late. The researchers behind the previously mentioned USP/UFMG/Agência Lupa study responded to WhatsApp’s claims of technical infeasibility in a New York Times op-ed, saying: “In India, it took only a few days… the same is possible in Brazil.” Experts who have warned for years that WhatsApp is fertile ground for disinformation say that WhatsApp’s management has been distant and unprepared as the crisis unfolded.

What can be done to minimize the harm done by WhatsApp in future elections in Brazil and around the world?

In terms of “quick fixes,” there are potential technical changes that could help restrict mass messaging and political spam. The USP/UFMG/Agência Lupa researchers developed three recommendations: further reducing the number of recipients of forwarded messages from twenty to five (as in India), restricting the number of recipients of new messages, and limiting the size of newly-created groups. WhatsApp dismissed these recommendations as impossible to implement ahead of the second round of voting in Brazil, but given more time, these should be organizational priorities. WhatsApp must also continue to vigilantly monitor suspicious activity and remove bots and bad actors from the platform.

WhatsApp’s long-term strategic direction is a much more complex question that asks fundamental questions about the role of mobile communications in modern society. Is WhatsApp accountable for the malicious or even criminal use of its services? How does a company founded on the principle of simple, secure communication monitor content without compromising user privacy?

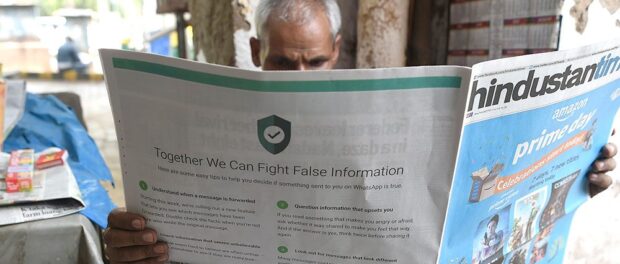

In India, under pressure from the Indian government following the murders, WhatsApp has taken steps towards accountability, such as taking out full-page newspaper ads urging users to be cautious and check sources, launching public education campaigns, and working to build an India-based team that would handle grievances. Taking a share of responsibility for educating users is a step in the right direction, as is building local teams that can cooperate more quickly with regulators and researchers than a Silicon Valley-based team, insulated and far from the action, ever could.

WhatsApp must serve as gatekeepers against disinformation, but society as a whole shares accountability for responsible usage. In many respects, the issues plaguing WhatsApp today are less about the application itself and more about its dominant position in the market and questions about how humans must adapt to a digital society. Policymakers and regulators, particularly the Superior Electoral Court (TSE), are equally culpable for being caught off-guard by this crisis, despite years of warnings from communications and electoral experts. Journalists and independent fact-checkers, who work admirably and vigilantly to confront lies and deception, must continue to expand their reach in an age of nontraditional media. Finally, individuals must understand that the Internet is not a safe or trustworthy place and diligently seek to verify information. Opportunists who are eager to manipulate people are everywhere and information that seems like it comes from close confidants often has nefarious origins.