During a February 13 appearance on TV Globo, Mayor Marcelo Crivella was prompted to discuss the situation in Rio das Pedras, a West Zone community that was among the many Rio de Janeiro neighborhoods hit by a devastating storm the week prior. His thoughts for the community’s future spurred outrage among residents, reigniting fears of eviction that the community had mobilized to stop in late 2017. The mayor’s remarks were not only offensive to many residents, but also misleading. In the televised interview, Crivella stated:

“Rio das Pedras greatly concerns me. It was the first project that I took up in the era of President Temer. Sadly, there was a strong militia group there. I think that the population of Rio de Janeiro followed this. There was a reaction from this group, whose [members] I know are all in jail now, and we can continue the project. Rio das Pedras’ problem [is that] there are tens of thousands of people—almost one hundred thousand people—whose sewage drains into the Tijuca Lagoon every day. It’s a serious problem—there’s no way we can remove the sewage normally because the ground is very fragile. Piping, which has been attempted many times, breaks. The elevating water pumps used to carry sewage to CEDAE [the State Water and Sewerage Utility]… don’t work.”

Crivella continued to assess the public security situation in Rio das Pedras:

“We already have a project to build around 11,000 houses that can resume now that the police have intervened. Now that we have security—now that we don’t have a militia group dominating the community, we can begin construction. Though they may not be completed under my administration, these public works will serve as a ‘redemption,’ so to speak, for many years of abandonment by the City of Rio de Janeiro.”

Rio das Pedras Commission members were outraged, seeing his comments as dismissive of their mobilization effort that halted his project in its tracks. The Commission had this to say on their group’s Facebook group:

“It’s sad to see politicians’ endless repertoire of excuses to downplay the poor administration and apathetic governance of late. We have heard that it’s not possible to create or maintain a project because of a lack of funds. We have heard that it’s the fault of the previous administrations. However, what we saw today is the accusation [by Crivella] that good citizens, who have bravely fought to keep the little that they have, are militia members and are the ones who are responsible for the lack of public investment in the community. These same residents fought tooth and nail against the evictions sought by the mayor.”

Another resident was quick to point out that the militia’s presence in Rio das Pedras had not been eliminated, as suggested by Crivella. The resident wrote: “There’s no longer a militia presence in Rio das Pedras—who knew? In the religious world of Crivella, isn’t lying a sin?”

A multitude of residents took offense at the mayor’s remarks—in part because of his insistence on completing a project that had already been defeated, but also because of his willingness to appear before the public and make misleading and outright false statements about their community. While Crivella estimated the population at 100,000, according to the Rio das Pedras Commission, over 180,000 people live in the community. The mayor’s plan to construct 11,000 additional homes fails to contemplate the tens of thousands displaced by his plan for the community. Furthermore, citing technical difficulties with implementing a basic sanitation system in the community, Crivella was quick to dismiss the R$64.7 million (US$17 million) infrastructure project carried out in Rio das Pedras by the State Secretary of Housing, constructed by over 200 technicians and workers over an eighteen-month period of planning and construction. Concluded in 2015, the project was supposed to provide over 30,000 people with basic sanitation and included paving a large section of the community’s roads to ease transportation needs. However, residents testify that the pumps have simply never been turned on. His comments on the inviability of infrastructure improvements beg the question: why would the mayor want to simply scrap millions of dollars in public spending projects that were completed less than a decade ago?

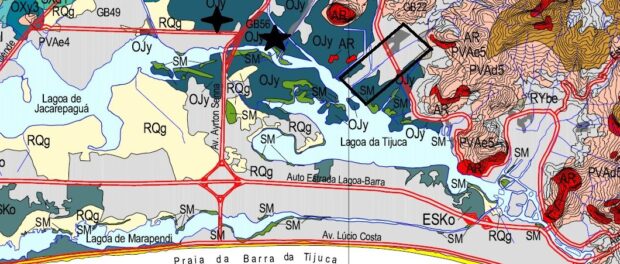

The interview focused heavily on flooding experienced by Rio das Pedras after heavy rains in early February. Located in a low-lying area, Rio das Pedras does, in fact, routinely suffer from flooding. However, the mayor also claimed that his old neighborhood Lagoa, in Rio’s South Zone, was hit hard by the rains. This touches on an important factor in the debate: flooding is a risk not only in Rio’s favelas but also in wealthy areas of the city located in watershed areas. (Coincidentally, or perhaps not so, the mayor’s current residence is located directly across the small lake from Rio das Pedras.) In examining the city’s soil map, it is clear that Rio das Pedras’ soil is the exact same type as the soil in most of Barra da Tijuca and shares similar soil with locations like the Metropolitana Shopping Mall and the Pan-American Village complex (used to host athletes during the mega-event and then sold as luxury apartments). An official map from the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (EMBRAPA) shows the proximity between Rio das Pedras (black rectangle), Vila Pan (five-point star), and the Metropolitana Mall (four-point star); grey coloring denotes developed areas.

Geographers from the Fluminense Federal University (UFF) note that flood risks have been exacerbated across the city due to poor management over the decades, such as the implementation of strategies like channeling rather than long-term urban resilience strategies. This is particularly concerning as Rio is projected to be the city worst affected by climate change in Latin America. The UFF geographers report: “These poorly planned construction projects are representative of a lack of adequate urban planning that takes into consideration the topographical conditions of the terrain as well as an efficient urban drainage system. Despite in theory having a rainwater management plan, in practice, the City of Rio de Janeiro applies very few flood prevention measures.”

The area surrounding the Rio das Pedras River was routinely subject to canalization projects implemented as early as the 19th century when this was a coffee growing region. In the 1950s, the National Department of Construction and Sanitation carried out major projects in the area such as digging the main canal in the community in an effort to drain and maximize usable land. According to the UFF geographers, this project did not take into consideration the maximum floodwater level that the canal could handle or the impermeability of the region’s soil. However, contrary to the mayor’s claim that the community is situated in an “at-risk” area, in environmental risk assessments conducted under the administration of former mayor Eduardo Paes in 2013, only fifty houses—all of which lie on the edge of Vila Pinheiro near the hills—were found to be at-risk to the point of needing to be removed. Instead of recommending removal, the assessments concluded that land titling, limiting certain developments, defining zoning areas, and creating a transportation plan for the community should be prioritized.

Deconstructing the Narrative

The Rio das Pedras Commission has a vastly different view of the community and their future than that advanced by the mayor. Working to mobilize the community during their anti-eviction struggle in 2017 brought the group together and put them in touch with thousands of community members. They experienced firsthand the difficulties facing residents, but also the remarkable and inspiring stories brought to life by community members. Commission member Andréia Ferreira recalled that journalists and politicians rarely visit Rio das Pedras and when they do, it’s to report on the negative aspects of the community, much like Crivella did in his televised comments. Ferreira reflected:

“It’s as though there are only bad things in favelas, when exactly the opposite is true. When there is drug trafficking in a community, the media gives the impression that there are only drug traffickers there. It’s not like that—they are the minority—and yet [the media] makes it seem like they’re a majority. People fight against it, fight to be good people—and yet they’re beaten down every day. The community should be praised in the news on a daily basis because these people are trying to overcome the injustices imposed upon the poor. These are people who have the odds stacked against them and are still amazing people.”

Despite the unfounded negative mainstream media narrative surrounding Rio das Pedras, by the end of the community’s struggle against eviction in 2017, the Rio das Pedras Commission had gained a huge following: a Facebook group with over 17,000 members and an even larger fan base within Rio das Pedras itself. Two of the group’s most vocal members, Lorena Carvalho and Andréia Ferreira, realized they had changed the fabric of the community through their year-long mobilization efforts. Barely able to get through a day without being sought for assistance, they decided to use their reach for good.

Ferreira reflects:

“Over the years, we realized that when election time came, politicians would appear, do a ‘makeover,’ and disappear. Other than this, no one ever shows up here in the community. Today, Rio das Pedras is abandoned, as it always has been. We saw that together—never alone—we were able to solve some problems. Here in Rio das Pedras, there are people who go hungry. Who helps these people? No one. So we realized that if we didn’t roll up our sleeves and work to address these issues, these children were going to die. Of course, things should be different—but unfortunately, they’re not. So in addition to paying our taxes, we have to work to do what the government fails to do.”

In 2018, the Commission officially shifted its focus to address the community’s needs more broadly. Using the hashtag #TogetherWeAreStronger (#JuntosSomosMaisForte), widely used throughout their 2017 resistance effort, the group—spearheaded by Ferreira and Carvalho—works to provide for the basic needs of the community and to provide a safety net where the government has neglected to do so. In the words of Carvalho, “We feel good when people are doing well.”

Projects

After seeing the Commission’s enormous impact on the Rio das Pedras community, the Residents’ Association decided to open up a space in its building for the group to work and asked for them to take over their two existing projects: academic tutoring and ballet classes. The tutoring program aims to provide additional educational support for kids who are struggling—a much needed and utilized project given the history of public neglect in Rio das Pedras’ schools.

With the help of other community members, Ferreira and Carvalho have been hard at work trying to provide as much as they can for the residents of Rio das Pedras. Several major projects have taken off, many additional classes have been launched, and community-wide events have attracted thousands. The following is a list of social activities and projects organized by the Commission in 2018:

- Adult Literacy: The Commission noticed throughout their mobilization efforts that many community members were unable to read documents or sign their names. The group has launched free adult literacy classes taught by a professional volunteer.

- Embrace a Senior Citizen: This project enlists volunteers in the community to visit and provide support to elderly residents in Rio das Pedras—whether that means providing a haircut, making a necessary phone call, or simply stopping by for a visit.

- Soccer Club: The most recent project was the launch of a youth soccer team. Young boys and girls were given the opportunity to sign up and the group was able to collect over one hundred donated jerseys.

- Solidarity Bazaar: A local bazaar was started where community members can donate used items like clothing and toys. The items are then given away to those in need.

- Job Placements: This project connects local employers with workers in need of jobs. The group collects resumés from residents and distributes them to local businesses that sign up for the project.

- Consultations: The group has hosted several events where residents could sign up for on-the-spot consultations with medical and legal professionals.

- Events: The group hosted a community-wide movie night, and gave away 700 basic food baskets and 1,000 toys for Christmas.

- Free Classes: In addition to ballet, the group now hosts hip hop, capoeira, and three different self-defense classes—all of which are free of charge and led by volunteer teachers.

Reflections

The victories and improvements achieved by the Commission attest to the power of mobilization and the strategic use of scarce resources to benefit the community as a whole, especially in the face of mounting government pressure. All of their work is made possible by donations and volunteers who are not financially compensated. However, these successes are also a testament to the strength of the resistance efforts led by the Commission in 2017. When asked how the Commission was able to get volunteers, donations, and resources, Ferreira responded: “It’s simple: access to information. People in the community don’t have access to information… When the Commission was formed, we went to the Public Defender’s Office, to the Rio City Council, to Vila Autódromo (to learn from their resistance efforts). The Commission went after the information that these residents lacked. From that moment on, the community began to trust us a lot. Along the way, we also learned a lot together with the community, and one of the greatest things we learned had to do with community unity. In everything that we think about doing, we think about everyone. We saw the strength that we have in numbers.”

The Rio das Pedras Commission’s work exemplifies the power of community organizing and the impact residents can have when they provide for one another in the absence of government support—as well as the power of information. In 2017, they sought the truth behind Crivella’s planned verticalization project. What was presented as a multimillion-dollar upgrading project for the community was likely going to result in the eviction of many residents—yet it wasn’t until residents mobilized that they discovered this information. The Commission subsequently organized for busloads of residents to occupy City hearings on the project in an effort to educate the public. It is now quite obvious that information was being purposely withheld or misconstrued in the hopes of speedily approving a project that would have done substantial harm to thousands of residents of Rio das Pedras. “Increasingly, the government wants people to remain ignorant so that they are incapable of fighting for their rights,” stated Carvalho.

This is not lost on Carvalho and Ferreira. In fact, they acknowledge that while their projects immensely help those in urgent need, the community truly needs government development and investment, specifically in the areas of health and education. Ferreira’s own mother, who has a grave medical condition, has been on an emergency waiting list to see a doctor for over a year in order to then have an operation or receive a prescription. She is also unable to travel outside the community. Ferreira reflected on the situation of residents in similar circumstances: “You’re unable to be seen at the hospital. You can’t access your right to education. Things will only change when people have access to education—when people have the opportunity. Healthcare is another priority—no one can do anything without their health. Any public official must start with two basic principles: healthcare and education. These are two things that I haven’t seen in my 36 years here. No one has ever come to provide them, and I haven’t seen anything change because the situation will only change once we have [healthcare and education].”

Despite the renewed threats, the Commission is already hard at work promoting their projects for 2019. They plan to keep a watchful eye on the administration’s plans for the community and are ready at a moment’s notice to jump back into action. This year, they hope to add more social projects on offer.