On Monday, April 8, residents, community organizers, civil society organizations, and politicians gathered for a public hearing at Niterói’s City Hall to discuss the low-income housing crisis in the city across the bay from Rio de Janeiro.

The event was hosted by two Niterói city councilors, Gezivaldo Ribeiro de Freitas (Renatinho) and Paulo Eduardo Gomes with the participation of Rio state representatives Flávio Serafini and Renata Souza—all from the Socialism and Liberty Party (PSOL)—as well as representatives from the Land and Housing Nucleus (NUTH) of the State Public Defender’s Office and the Nucleus of Housing and Urban Studies and Projects (NEPHU) at the Federal Fluminense University (UFF).

The hearing was held on the ninth anniversary of the Morro do Bumba tragedy, which resulted in 46 deaths and left thousands homeless. At least fifteen communities were present to discuss issues facing residents of favelas and housing occupations in Niterói.

The following are five major takeaways:

1. Niterói Residents Are Still At Risk

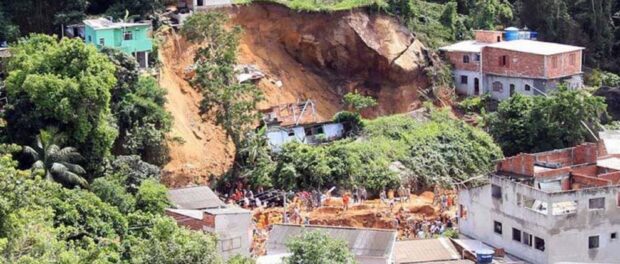

The rains of April 2010, which culminated in a massive landslide in the community of Morro do Bumba—killing 46 people and leaving thousands for nearly a decade now without dependable housing—laid bare the state of housing in Niterói.

Nine years later, little has been done to remedy the situation for the victims or other communities in the city. In fact, according to the Niterói-São Gonçalo Housing Struggle Forum, the civil society group responsible for pushing for the public hearing, the majority of those affected are still without housing and many aren’t receiving the social rent payments promised by City authorities at the time. Interviewed in a recent article, the president of the Morro do Bumba Victims’ Association emphasized this fact, stating that only 1,500 of the 3,200 victims without housing after the tragedy have been rehoused, while the rest receive social rent of R$400 (US$100) per month—which residents say isn’t enough to rent a house or apartment in an area that is not subject to environmental risk. State representative Serafini also recalled that this was the fifth public hearing held since the disaster to discuss the state of housing in the city of Niterói.

According to Niterói city authorities, 3,000 houses have been handed over, and over seventy construction projects have been finished in an attempt to secure communities at risk. In fact, during the hearing, the Municipal Sub-Secretary of Housing echoed these points and stated that the City is currently working on land regularization in five major favelas in the city. Nonetheless, residents still live in danger and fear.

In 2015, the City hired a company to do a diagnostic mapping of communities in risk areas. While it was scheduled to be completed in February 2018, community members continue to wait for results. With little to no progress done on construction or housing projects, families in the Morro da Boa Esperança favela suffered tragedy on November 10, 2018, when a landslide in the community killed fifteen people. The president of the Residents Association of Morro da Chácara e do Arroz commented that the community had to organize and complete construction projects themselves and eventually sued the City before anything was done in their community, which is also at risk. Several community members present touched on their feeling of worry and concern for danger with regard to their housing situations. The simple fact is that thousands of residents of Niterói’s 87 favelas and several occupations do not have adequate housing.

2. Niterói Has the Resources to Fix the Problem

Niterói is the most desired non-capital city to live in in the entire country. The city is close to Rio and is relatively safe compared to many large cities in Brazil, with the highest Human Development Index in the state of Rio and the 7th highest in the country. All of this is to say that Niterói is fairly well off. In fact, Niterói is set to rake in millions of dollars from pre-salt offshore oil reserves. In late March, the city created a fund for these royalties with an initial deposit of R$102 million (US$25 million). According to projections, R$2.5 billion (US$625 million) will be paid out over the next twenty years; the City of Niterói will take 10% of that.

The Niterói-São Gonçalo Housing Struggle Forum is asking the City to use these royalties to pay for a more comprehensive housing plan and create a community panel that will control all resources destined for housing. The City of Niterói’s 2019 budget also includes R$3 million (US$750,000) set aside for the expropriation of land near Boa Esperança that should then be used to build public housing for those in the area and to monitor and carry out a mapping study of the area. The money is there, but is the political will?

3. Current City Solutions Aren’t Sufficient

The City has been working on three major Minha Casa Minha Vida (MCMV) public housing complexes. Several hundred apartments have already been delivered to residents and almost a thousand more are expected to be completed before the end of the year. One of those housing complexes, Jardim das Paineiras, is expected to be finished by the end of the year with a total of 540 apartments and was offered to residents of Boa Esperança, Preventório, Peixe Galo, and Salinas. While many residents genuinely want to be placed in public housing, they have some valid critiques. First, the MCMV complex is located in the Badú neighborhood in Pendotiba, approximately ten kilometers from Jurujuba—the district where Preventório, Peixe Galo, and Salinas are located.

Residents are also worried about finances; it is widely known that moving to an MCMV complex means higher bills. This can be especially difficult for low-income residents who aren’t prepared to pay high utility bills. Residents in the area typically make minimum wage or less and cannot afford them. Moreover, the group canvassed the area and found out that there were almost no openings in area schools or daycares and there was also no family medical clinic. With over 1,500 new projected residents, this would be a huge concern.

4. Negotiations Have Stalled

The political situation in Niterói is complicated: former mayor Rodrigo Neves was jailed late last year on corruption charges. Many of the communities were negotiating with the mayor’s office and have seen those negotiations stall completely with the new mayor, Paulo Bagueira. There is perhaps no better example of the complexity of projects being stalled than the Landless Workers Movement (MTST) occupations. In 2015, 550 families occupied an empty lot in the Sapê neighborhood in what became known as the April 6th Occupation with the goal of pressuring City authorities to cede land for the construction of housing through channels such as Minha Casa Minha Vida – Entidades (MCMV-En), which provides federal funding for self-managed housing cooperatives. Over the next several years, much work and mobilization was done on the part of MTST—including a re-occupation in 2018 given the City’s inaction—and while there were many bumps along the way and a shift away from MCMV-En, a plan moved forward with the eventual agreement that the City would finance 50% and MTST would finance 50%.

Local MTST leader Danilo Cuin summarized: “Stemming from a legitimate civil society struggle, the mayor acknowledged various families’ right to housing. He expropriated a piece of land, indicated in the Master Plan of the City of Niterói as an Area of Special Social Interest (AEIS), and promised to give it to the families, by way of the MTST. He even promised to pass along resources to help in construction. The model and format are innovative and will go a long way to put Niterói ahead of its time, serving as a first step in what would not only be a return to municipal and local financing of housing, but a better way in all aspects to guarantee rights and a socially organized demand.” However, in 2018, the project was almost completely stalled—even with R$500,000 (US$125,000) approved by the City, with the City government signaling a desire to return to more traditionally financed MCMV housing. Additionally, with a new mayor, MTST is currently still waiting for a response despite reaching out multiple times.

5. Eviction Still Looms Over Residents’ Heads

While some residents expressed a desire to be relocated from their communities, a large majority stated that they preferred on-site upgrading projects to removal. This is a sentiment echoed across the Rio de Janeiro Metropolitan Region. After community members experienced landslides in Boa Esperança and some residents received eviction notices in Jurujuba, those impacted are receiving social rent payments until their situations get better—but many recalled that they haven’t seen any construction projects in their communities. This furthers fears that residents will simply be moved to public housing once it’s ready instead of enjoying upgrading projects in their communities.

One community that is currently under eviction threat is the fishing community of Itaipú. Ronaldo Lobão, UFF professor and anthropologist has studied the community and has found artifacts which confirm the community as over one hundred years old. According to Lobão, the land was divided up and sold in the 1970s without looking to see if the area was occupied. Now the community is fighting the “new owners” struggling to prove its right to the land, parts of which are protected by the National Institute of Historic and Artistic Heritage (IPHAN). The Niterói-São Gonçalo Housing Struggle Forum calls for an immediate end to the policy of eviction and an end to eviction threats in Itaipú.

In summary, the communities and organizations in attendance demanded:

- A more in-depth analysis of the MCMV project in Pendotiba to ensure that all of the needs of residents placed there are met;

- That the mayor reinitiate negotiations with the MTST and other communities, such as the Mama Africa Occupation;

- An immediate stop to eviction threats;

- The prioritization of upgrading, risk reduction, and land titling in communities across the city;

- The updating of the city’s housing plan with the creation of risk reduction and drainage plans; and

- That oil royalties be used to pursue these goals and that all projects for low-income housing be subject to oversight by a board of community leaders.