On Thursday, May 23, the seventh session of the Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry (CPI) on Flooding took place at Rio de Janeiro’s City Council. Focusing on the role of Rio-Águas, Rio de Janeiro’s municipal agency responsible for rainwater management, sanitation, flood control and prevention, the session marked the beginning of the CPI’s third phase, during which committee members seek to “understand the planning process and maintenance, prevention, and emergency response measures taken by responsible municipal agencies annually and during heavy rains.” As such, CPI members questioned Rio-Águas president Marcelo Jabre Rocha and technicians Wanderson José Santos, Wilmar Lopes, and Janaina Rodrigues on the agency’s planned preventative actions to mitigate the impacts of future natural disasters.

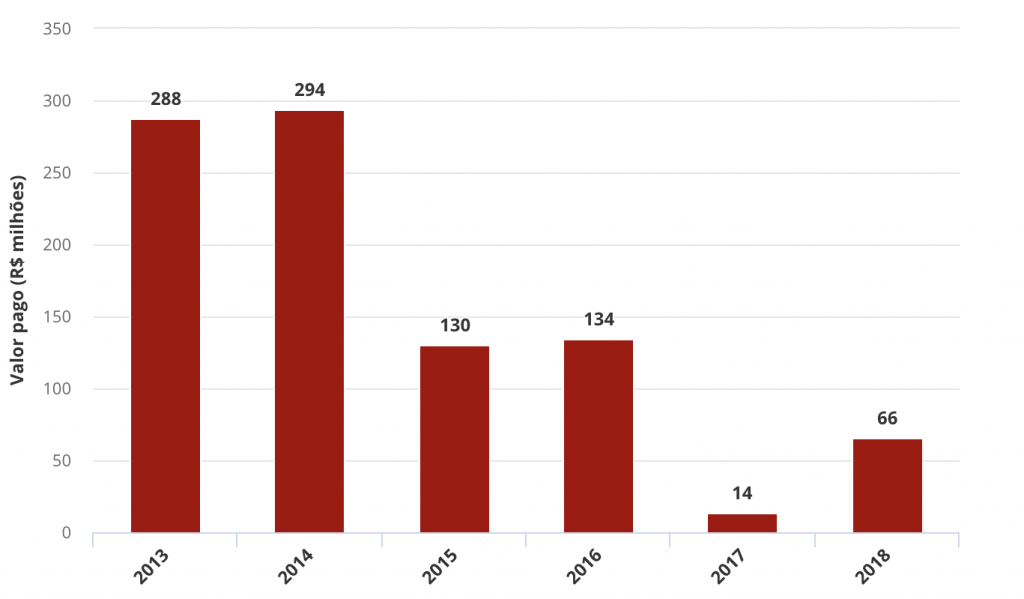

Founded in 1998, Rio-Águas has experienced major funding cuts in recent years as the City decreased the agency’s budget from R$531 million (US$132 million) to R$224 million (US$56 million) between 2013 and 2018. According to Rocha, funding for drainage system maintenance has been on the decline since 2014. Likewise, the budget for flood control has been cut by more than 77% in the past five years, shrinking from R$288 million (US$72 million) in 2013 to just R$14 million (US$3.5 million) in 2017 and R$66 million (US$16.5 million) in 2018.

City councilor and CPI member Teresa Bergher (Brazilian Social Democracy Party–PSDB) pointed out that the City only spent R$6.35 million (US$1.6 million) of the available R$300 million (US$75 million), equivalent to approximately 2% of the allocated funds, on flood control and landslide prevention programs. In the absence of adequate preventative measures, the rains that hit Rio in February and April caused landslides and severe flooding in neighborhoods across the city, leaving seventeen dead and many more homeless. The three prevention programs created by the City—flood control, urban water quality, and geotechnical stabilization—have all received well below the necessary level of funding to carry out proper preventative actions.

Additionally, Bergher emphasized that no funds were spent on urban drainage systems or hillside containment works in 2019. Bergher stated that “this is not the result of a lack of funding”—the City has allocated around R$20.77 million (US$5.2 million) for urban drainage system maintenance. According to a report published by Bergher’s office and broadcast on GloboNews, of the fifteen programs created by the City to prevent flooding, only four ever received funding. Those four programs did not include siren maintenance—leading to activation failures during recent storms that left residents with no warning.

Rocha also stated that Rio-Águas is currently facing a personnel deficit. By 2020, five Rio-Águas engineers will retire and begin to receive their pensions. The agency has already requested the hiring of ten engineers for future development and planning, but these investments require significantly more funding than the amount currently allocated by the City in light of recent budget cuts. This was the main concern expressed by city councilor Tarcísio Motta (Socialism and Liberty Party–PSOL), president of the CPI on Flooding, and other committee members.

Bergher revealed that of the R$108 million (US$27 million) available in the municipal budget for flood control, R$11 million (US$2.75 million) was spent; of the R$22 million (US$5.5 million) available for monitoring water quality, R$6 million (US$1.5 million) was spent; and of the R$66 million (US$16.5 million) allocated for the expansion of sanitation within the city, approximately R$781,000 (US$195,000) was spent.

City councilor and CPI member Rosa Fernandes (Brazilian Democratic Movement–PMDB) reiterated the need for the Mayor’s Chief of Staff to continue to monitor the City’s budget in order to ensure the necessary funds and resources are going to the parts of the city hit hardest by the recent and unusually strong rains. While favelas such as Rocinha, Vidigal, Babilônia, and Horto were severely impacted, upscale areas such as Jardim Botânico were also damaged by the floods.

Towards the end of the meeting, Motta summarized steps that need to be taken in order for Rio-Águas to fulfill their promises for water control and sanitation of Rio de Janeiro. First, the City must guarantee the allocation of funding for Rio-Águas so that the agency’s work can continue unimpeded. Second, the organization should publicly disclose its master plan for rainwater management—a plan that Rocha says is “in development, but not yet complete.” Third, and perhaps most important, there needs to be a concrete definition of the agency’s priorities, including Motta’s own suggestion of a favela sanitation program.

Seeking greater public accountability, Motta proposed a bill—co-signed by CPI rapporteur Renato Cinco (PSOL) and committee members Rosa Fernandes and Teresa Bergher, along with several of their fellow city councilors—to block Mayor Marcelo Crivella’s plan to subordinate Rio’s Center of Operations (COR) to the Municipal Secretariat of Public Order, shifting responsibilities away from the Mayor’s Chief of Staff. Motta stated, “The Mayor’s Chief of Staff is best suited to coordinate the various [municipal] agencies in times of crisis. Allowing COR to be supervised by the Municipal Secretariat of Public Order makes no sense and is reckless for the city.” Rio’s City Council approved the bill on Thursday, June 6.

At the end of the hearing, Motta stated that the favela of Rocinha would be the next topic of debate for the committee. The 8th session of the CPI on Flooding was held on May 30 with representatives from Rio’s Civil Defense and the 9th session on June 6 with representatives of COMLURB, Rio’s municipal waste collection utility. The next session is planned for June 10 with representatives from COR.