This is the second of two articles on Black July, now in its fourth annual iteration. Both articles focus on the three roundtable discussions that took place on July 25, day two of the three-day event. According to Black July organizers, the annual event is “an international collaboration in the fight against racism, militarization, and apartheid, undertaken by the mothers and family members of victims of State violence and various groups that make up the movement of favelas in Rio de Janeiro.” Read part 1 here.

Roundtable 3: Genocide—From Drugs to Prison

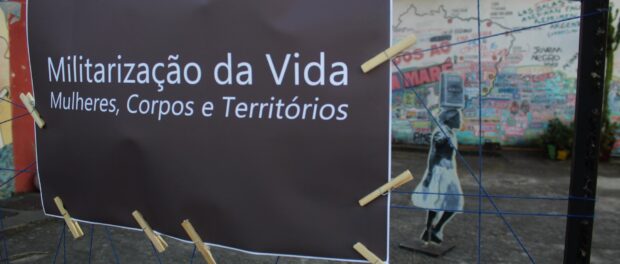

As a community writer from Rocinha reporting for RioOnWatch, I can affirm that the theme of militarization of life—the focus of Black July’s second roundtable—speaks to my trajectory as a resident of Rio’s favelas for over 38 years. For those who live outside this reality, the militarization of day-to-day life works like this: it’s leaving home in the morning to go buy bread with your child and the first thing you see is a soldier with a rifle pointed at the bakery; it’s checking in on social media to see if the police operation that began during school hours has finished; it’s checking in to see if your child is alright and if it is safe for them to come home from school; it’s waking up at 6am with a helicopter buzzing over your roof, blasting announcements that you should remain inside your home, and that leaving for work might actually cost you your life; it’s avoiding carrying common household objects like umbrellas, drills, and cellphones on days with police operations so that they’re not confused with a gun and so you don’t become a target. The examples are infinite, but this cycle has gone on for years in the streets of so many favelas. And this kind of violence is unheard of in the upper-class neighborhoods where many favela residents work. It was on this topic—this denied right—that the second roundtable began debating.

Sitting on the panel were: Cristiano Silva de Oliveira from the Eu Sou Eu (I Am Me) collective, which focuses on the question of life in prison, and a participant in the State Front for Disincarceration; Eliene Vieira, a member of Mothers of Manguinhos and of the Manguinhos Social Forum; Lourenço Cezar of CEASM and the Maré Museum; and Mônica Cruz of the NGO Global Justice (Justiça Global), also a resident of Manguinhos. On the question of who most experiences the reality of militarization (war on whom?), the panel’s participants were in complete agreement: it is those who have their lives shattered daily by State actions that target only one territory in the city—its favelas.

Cezar spoke on the role of left-wing politicians and their effort to build a new scenario in relation to public security in the favelas. “We live in our little world here, but there are people who have been studying this for years and could be bringing their knowledge here to create a project that is ours. I know that in the Northeast of Brazil, for example, certain states have drastically reduced their levels of violence. We need to know what they’re doing, because we are in the line of fire, taking fire from all sides. It’s hard for us to step out of the crossfire and reflect on this. We need more tools to get out into the field and convince more hearts and minds. That’s what I feel is missing.”

Cezar’s words point to a clear need for bottom-up public policies. As he indicates, the only thing that is known about favelas is their place in the war on drugs: the culture made up of real people and families goes unseen, reducing the lives of common citizens through prejudice and criminalization. As Oliveira put it, “Our bodies are killable.”

Vieira, one of the mothers that make up Mothers of Manguinhos, echoed, “I’ve been hearing about this so-called failed State for a while now. But for those of us that live in the favelas, this failure has always been there. My son had his chest shot through [by the police] and was thrown in jail. It was then that I realized that I needed to speak up not only for him, but for all youth. Before, I blamed myself. I blamed my son. But then another woman taught me that we have rights.” Vieira finished, “the police aren’t for killing, they’re for protecting.”

Roundtable 3: Black Women—Our Resistance Has Come Far

The third table of the day was made up of black women and one trans woman psychologist, all there to debate racism. Since the era of colonization when Africans were forcibly brought to Brazil, until modern day, racism has plagued its victims psychologically as well as physically. To speak of this pain, which ravages black people and especially low-income blacks, is to speak of seemingly endless pain. However, in testament to the importance of Black July, these women took the stage to form a powerful group. Some transformed their pain into efforts to give strength to other black women who had lost their sons to the prison system or to death.

On this table—which took place on July 25, Day of the Black Latin American and Caribbean Woman as well as Tereza de Benguela Day—sat Mônica Cunha, of Movimento Moleque and the Human Rights Commission of Rio’s State Assembly (Alerj); Saney Souza of the West Zone Women’s Popular Committee and the Rio Urban Agriculture Network; Irone Santiago, resident of Maré and mother of Vitor, who became paraplegic at the hands of the State; and Maiara Fafini, psychologist, trans woman and also member of the Human Rights Commission at the Alerj.

Cunha brought up the alarming number of deaths among black men, warning, “We are constantly heading to the front lines of this battle to make sure that our own don’t fall victim. Yesterday at a meeting with Sueli Carneiro, she said that she sees a lack of male black youth in our activism, that she sees mainly women. And I told her ‘that’s because they’re dead or in jail. They aren’t getting into college in the same proportions. Right now, it’s us women that are getting in more than they are. This is nothing to be happy about though, to be treated as a gender dispute as we used to… that’s not it anymore… Black men are dying or being locked up. What sort of a victory is that? What gain? We continue showing up and getting our degrees and seeing less and less of our brothers. Where are those that should be here at our side?” Cunha added “Genocide doesn’t just come from gunshots. It happens earlier, with the lack of basic necessities: health, education, housing, and nutrition. All of this is part of genocide. The gunshot is just the end.”

On another important topic, Saney de Souza brought up the question of the situation currently faced by social movements that defend minorities. “In the analyses that we have undertaken from some time ago until now, above all since the coup [against former President Dilma Rousseff], it seems things are likely to get worse. We will see the persecution of social movements, persecution of individual figures… I ask myself: Was there ever a time that things were good? When things were going just fine [in the favelas]?” said Souza.

Fafini closed the discussion with a quote from writer and researcher Muniz Sodré: “Don’t trust anyone who sees only the abstract and the astral, without paying attention to the territory.”

The day ended with empathy and a welcoming air, though with many questions left unanswered. Above all, the day indicated a need for a more collaborative path, one of united leadership and community-based communicators seeking to fill the gaps left by the State for ages. Now, more than ever, this movement must be by and for us. In the words of Soledad Ortiz Vasquez, invited to Black July from Mexico’s Council for the Defense of the Rights of the People (CODEP), what’s needed is “unity among the people to fight the classic enemy.”

Hearing the day’s talks reminded me of the struggles of those close to me, of friends, neighbors, and family members. None of this is new and, unfortunately, the topics remain the same because the attacks remain the same. We of the favelas would tell of births, parties, and meetings rather than death, but the system does not allow us to live normal lives, to speak only of trivial things. All of this brought to mind the song Amenidades, by Rubia Divino. I’ll leave it to her poetic lyrics to close:

“A body stopped on the road, exhausted from walking

On TV, on the radio

Eyes, ears behind glass feel the blood pour,

Minorities crucified for lack of love that kills

The rock hits the girl, the black man is beaten, a year

of irrationality

In congress, a coup, a shot

Shot by a parliamentary anti-christ, looking to crush, to condemn the poor youths of the nation

The woman cornered in the alley with no implication… hopelessness

On setting foot in this world, the system that plans to remove me

I wanted amenities, to speak of amenities, but when will this end?

I wanted amenities, if you want amenities get in the closet and go back to Narnia

They don’t respect creed

They don’t respect choice

They don’t respect birth

They don’t respect the constitution

They don’t respect the body

Where will this end?”

Listen to the song Amenidades below:

This is the second article in a two-part series on 2019 Black July. For part 1 click here.

Carla Souza is a teacher by training and loves her job as an early childhood education teacher. Raised in Rocinha, she understands her existence as a black woman and favela resident as a focus of struggle and resistance in the world.