In celebration of the 50th anniversary of New Communities Inc., the world’s first Community Land Trust, and as planners and community members alike gather to celebrate October 2-5 at the Reclaiming Vacant Properties Conference 2019 in Atlanta, Georgia, RioOnWatch issued a call for articles highlighting the current growth of the CLT movement worldwide. Contributors wrote in from around the world, with stories about the expansion of CLTs—both in number and in approach—in Mississippi, the United Kingdom, Belgium, France, Puerto Rico, Rio de Janeiro, and Florida. This varied series aims to disseminate news of the successes of the CLT model as it adapts to new times and circumstances, bringing greater attention to this innovative solution to guarantee the right to housing and community development, and its potential in resolving the global housing crisis.

Today’s piece, by UC Berkeley Law student and former Catalytic Communities intern Alix Vadot, looks at the rise of CLTs in Belgium and their experience in mitigating the effects of skyrocketing housing prices.

For more information on CLTs and their potential for Rio de Janeiro’s favelas click here for text and here for video.

When housing prices in the Brussels Region began to rise around the year 2000, nearly doubling in the period from 2000 to 2010, those with the fewest resources were forced to move out of the city center, away from their communities and job opportunities. In response to the gentrification and socio-economic crisis that ensued, people and organizations came together to find a solution. One of these organizations was Belgium-based NGO Periferia, an international non-profit which got its name due to influences from social experiments carried out in Brazil, and active in the Belgian region of Wallonia, Brussels, the Southwest of France, and in Latin America. After being introduced to the Community Land Trust (CLT) model by Periferia, a group of Belgian non-profits came together and mobilized to work intensively on the creation of the country’s first CLT.

Modeled on their American counterparts, Belgian CLTs follow a typical tripartite participation scheme, in their case with decisions made based on input by the following three groups: the surrounding community, the government, and current and future residents (for a more in-depth description, watch the following video, or click here).

In order to make sure such a model could be applied to the Belgian context, Periferia, Maison de Quartiers Bonnevie, and other non-profits carried out a feasibility study, as requested by the State Secretary in charge of social housing for the Brussels-Capital Region (which also funded the study) in 2011. The study answered a number of questions, from what legal mechanisms should be used to separate ownership of land from ownership of the buildings, to which partners to involve in the process, and what methods of financing and management would be best for the CLT.

With the study’s completion, the next step was to establish actual CLTs as real solutions for social housing. Founded in late 2012 as Belgium’s first CLT, CLT Brussels (CLTB) was fortunate enough to receive extensive financial support from the European Sustainable Housing for Inclusive and Cohesive Cities (SHICC) project as well as the Brussels city government, which committed to financing the operations of CLTB as well as subsidizing investment for land acquisition and building construction. The European Union also committed to funding specific projects, and granted Care and Living in Community (CALICO), which plans to build 34 housing units in the Forest area of Brussels, a €5 million (US$5.49 million) subsidy. CLTB is also a social housing partner in the Brussels Housing Bill—demonstrating the program’s early support from local government. Brussels’ Flemish neighbor, the city of Ghent, on the other hand, has experienced scarce funding, slowing down the project’s take-off there.

According to Joaquin de Santos, SHICC Program Manager at CLTB, there are various conditions essential to a CLT’s success that require special attention in the Belgian context. For one, the American “thirds” model of participation asks that each group be an active participant in the process. Beyond the traditional social housing offices within the government, collaboration with the local community as well as current and future residents in defining and respecting cohabitation rules is essential, and the underlying economic, urban, and political contexts are all crucial factors. Without sufficient land and funding to acquire said land, the establishment of a CLT model is simply not feasible. In Belgium, high land prices are currently a significant barrier to large-scale development of CLTs. The ability of residents (usually low-income families) to obtain social mortgages is also important. Finally, broad support among local organizations, government, and neighboring communities is essential. Without this last ingredient, the core nature of a CLT will be compromised.

A number of steps are involved in the process of turning an idea into an established housing project:

- The first is land acquisition. In Belgium, it is best to go through a Contrat de Quartier Durable (sustainable neighborhood contract), a collaborative plan between the Region, the commune, and the residents of a neighborhood, helping to purchase land at the best possible price.

- Next, a feasibility study is carried out to determine the number of housing units, as well as the architectural plan for the units. Because current CLT development is publicly funded in Belgium, the project must be submitted according to the rules of the Marché Public, whereby the architectural plan offer is made public to all architects.

- Following unit construction, residents are selected from a wait list. Once selected, they are asked to save every month and participate in a series of workshops related to various issues, including energy management, group dynamics, neighborhood integration, and more. Residents often end up being from the lowest income brackets (the maximum income level allowed to qualify for housing is around €24,000, or US$26,340, per year), many of whom are of immigrant background and do not speak French.

- Residents are also asked to take out mortgage loans—an otherwise difficult task considering their incomes and credit history. Residents may, however, seek assistance from the Brussels Fond de Logement, a social mortgage loan program.

- Once the CLT is established and underway, management and community support is crucial to long-term sustainability. An efficient management system should be designated from the start, ensuring that residents are aware of community and co-living rules, and continue to respect these throughout.

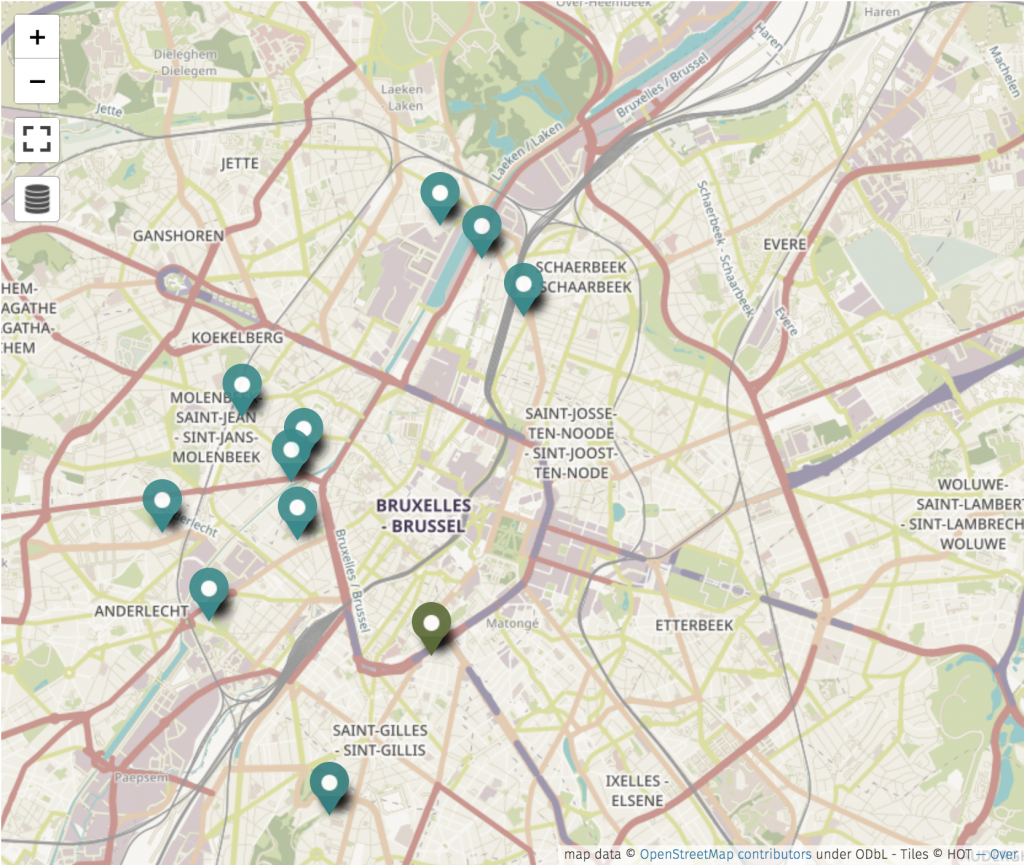

As of its completion in 2015, CLTB, the first CLT housing development in continental Europe, includes nine housing units and three more housing projects under construction. Five new projects are in planning, amounting to a total of 129 housing units. In Ghent, one project with 34 units is under construction, and two other housing projects with 19 and 5 units, respectively, are being planned. More detailed information about the CLT context is available here for Brussels and here for Ghent

The concept of participatory community development did not come unprecedented in Belgium. Prior to the founding of CLTB, the city was already home to related projects such as l’Espoir, a community garden and housing development for 14 families, which uses a participatory model similar to that of CLTs. Such projects have played a significant role in helping the city’s residents cope with rising housing prices and rebuild community ties that have severed as a consequence. CLTs provide a people-focused alternative to more traditional social housing projects, offering a place where low-income families can benefit from affordable rent prices and employment opportunities, all while becoming part of a community.

This is the third article in our series on the growth of the global CLT movement. Click here for more.