In celebration of the 50th anniversary of New Communities Inc., the world’s first Community Land Trust, and as planners and community members alike gather to celebrate October 2-5 at the Reclaiming Vacant Properties Conference 2019 in Atlanta, Georgia, RioOnWatch issued a call for articles highlighting the current growth of the CLT movement worldwide. Contributors wrote in from around the world, with stories about the expansion of CLTs—both in number and in approach—in Mississippi, the United Kingdom, Belgium, France, Puerto Rico, Rio de Janeiro, and Florida. This varied series aims to disseminate news of the successes of the CLT model as it adapts to new times and circumstances, bringing greater attention to this innovative solution to guarantee the right to housing and community development, and its potential in resolving the global housing crisis.

Today’s piece, by European Commission assistant and former Catalytic Communities intern Katja Majcen, explains the legal processes behind the growth of French CLTs.

For more information on CLTs and their potential for Rio de Janeiro’s favelas click here for text and here for video.

In France, the notion of habitat participatif (participative, self-managed and/or self-built housing) has had great success. Bolstered by the hippie movement and several decades of housing sector tension, support for the movement came to a peak following the tumultuous events of May 1968, amid growing pressure on housing markets and rising prices. In the 1970s, societal trends and community-oriented initiatives across the country began to give way to alternative solutions to conventional housing practices, flying in the face of the legacy of the Napoleonic Civil Code, where land and building ownership are closely intertwined.

Participatory projects continued to organize into the 2000s, especially in large cities such as Grenoble, Lille, Strasbourg, and Paris. Rising to address issues of access to housing, the projects were supported by the presence of powerful activist groups, including cooperative and self-managed movements, municipal action groups, the éducation populaire, and others.

In order to gain legitimacy and national visibility, these groups joined forces. In 2007, they began organizing annual national meetings, bringing together residents, architects, social landlords, representatives of public authorities, and others with the aim of spreading their actions and pooling their resources and know-how. A 2010 meeting in Strasbourg marked a true turning point, leading to the establishment of a National Network of Communities for Participatory Housing (RNCHP), including associations, professionals, and elected officials. The RNCHP is both a platform for sharing experiences and an operational tool for including participatory housing as a component of public policy. It is a network open to the community and other institutions, and also functions as a lobbying body.

At the same time, interest in the CLT model began rising in France in the wake of the successful implementation of CLTs in England and Brussels. At the end of 2013, the Community Land Trust France association was created to promote the principles and values of CLTs, adapt them to the French context, and increase awareness among groups and landowners.

The national network took regular part in the working group headed by then-Minister of Territorial Equality and Housing Cécile Duflot, lobbying effectively and gaining increased national recognition. The network also played a major role in the adoption of new legal structures to implement participatory housing initiatives, including CLTs, in France.

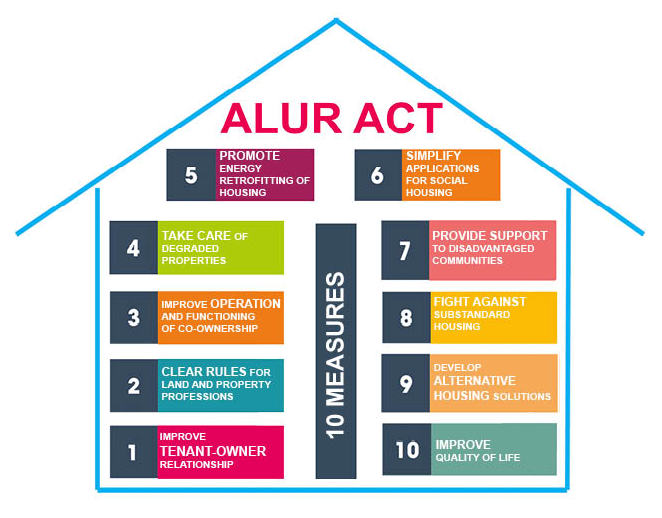

Unlike their counterparts in England and the US, which began implementation prior to gaining legislative support, French CLTs came about through the legislative process. After years of incubation in the associative and activist networks, participatory housing was first officially recognized and regulated in 2013, when Duflot submitted to the National Assembly a draft bill (project No. 1179), known as the ALUR bill. The text was discussed, amended, and voted into law in 2014, with a chapter entitled “Creating new forms of access to housing through participatory housing.” The text also included an article (L 200-1) that has been introduced into the country’s Construction and Housing Code, describing participatory housing as a citizen approach, allowing individuals to contribute to the design, as well as in the definition and, if necessary, the management and collective construction of, their housing.

The law thus allowed for the creation of the Organismes Fonciers Solidaires (OFS), based on—but not the same as—the Community Land Trust model. The law for Growth, Activity, and Equal Economic Opportunity, known as the “Macron law,” of August 6, 2015, completed the legal adaptations necessary by creating a bail réel solidaire (“real solidarity lease”) to better address certain constraints related to contract law, including a 99 year limit on emphyteutic leases (which oblige leasees to improve their property with construction), as well as to disassociate land from the building itself, decreasing the price of housing.

This new legal framework made viable “participatory housing corporations” aimed to support individuals in building or acquiring the property for their housing as well as shared spaces. These individuals are considered partners and each acquire shares corresponding to their lot. They each have equal weight in the decision-making process, actively take part in the design process, and where needed, in the management of the property.

These participatory housing corporations can take the form of an “allocation and self-development corporation,” in which each resident holds shares, or a “cooperative of residents,” adopting a logic of collective ownership where the residents have the dual status of partners and tenants. They then pay a monthly fee to reimburse the collective loan.

The French model stands out in terms of the role of the resident in the process. The essential role of the residents in English and US projects is related to their very local, neighborhood-level, anchorage. The French model, however, maintains a focus on the housing issue itself, with a social mission at a scope beyond the local level. Urban action in France remains largely the responsibility of the public community, which represents all the residents of the territory in a democratic manner. By accompanying the creation of a collective involved in the issue of housing, however, and by focusing more on the neighborhood itself, OFSs may encourage and support the construction of popular initiatives.

OFSs thus represent opportunities to encourage a new form of citizen mobilization in France. Their increased focus on residents could be key to overcoming the purely technical function of the OFS (that is, of land ownership) by drawing attention to the social role of the resident and by valuing this new form of disassociated property and its beneficiaries.

This is the fourth article in our series on the growth of the global CLT movement. Click here for more.