For the original article in Portuguese by Michel Silva published in Favela em Pauta click here.

No one buys print newspapers anymore because they only print bad news. This assertion makes sense when we consider how print newspapers present Rio’s favelas on their covers.

Over the months of March, April, and May 2019, I conducted an analysis of journalistic coverage about favelas across Rio print news to verify if they speak positively or negatively of Rio’s favelas. I, as a communication professional, always aim to take care in the publication of information. Who is going to read it? Who will it reach? What could happen to the people mentioned in the article? Is it of public interest or of interest to the public?

After 92 days of reading—carefully—the print editions of O Dia, Extra, O Globo and Meia Hora, I concluded that who sees the cover page sees no heart. Favelas and their residents are portrayed in a sensationalist way by these newspapers and television productions, just as they have been for decades.

Press professionals have cultivated a passivity of not questioning official statements, leaving witnesses aside. The editor, based in his or her subjectivity, determines what is included and what isn’t in the reporting. And so, even in the year 2019, we still see headlines labeling favela residents suspects or criminals, even when innocent, while labeling [middle and upper-class] youth from the South Zone as university students, even when guilty.

A 2007 study conducted by the Center for Security and Citizenship Studies (CESeC), with reporters and editors of the country’s main communication channels, showed that little has changed to this day. “The majority of professionals interviewed recognize that their outlets are greatly responsible for the characterization of popular territories as exclusively violent spaces. At the same time, they admit that the people of these communities are rarely portrayed by topics unrelated to drug trafficking and criminality,” the study indicated.

In my analysis of printed newspapers [today], I saw that culture, sports, economy, and the everyday difficulties faced by residents of favelas appears very rarely, especially when one considers the immense number of reports and articles about police operations, shootouts, and executions.

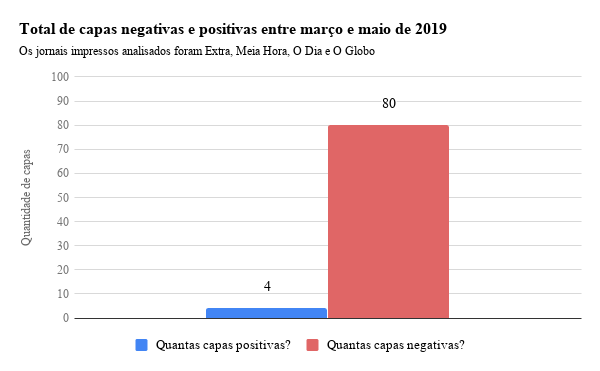

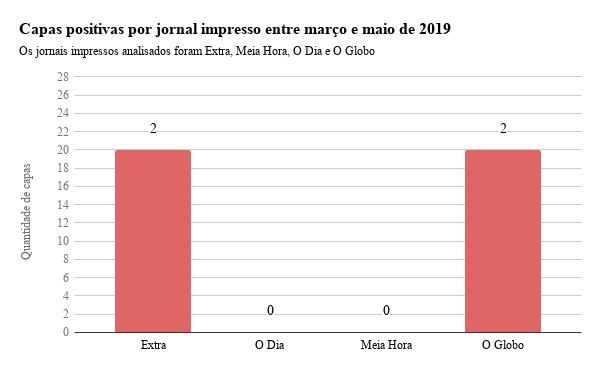

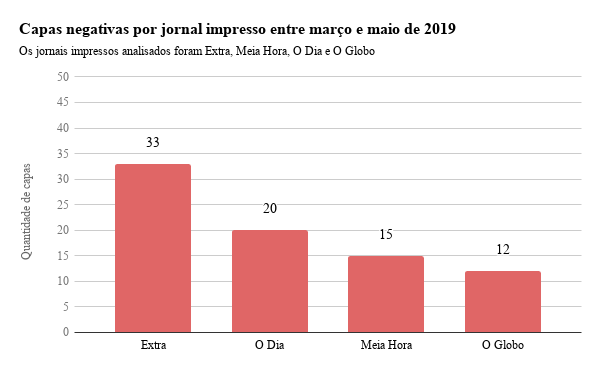

In 92 days, the newspapers studied published four positive cover stories, while negative stories occupied 80 covers. There were also days when the newspapers included no topics related to the favelas on their covers.

The newspaper Extra, of the Globo media group, printed the largest quantity of negative covers [click here for a comparison of international outlets’ coverage of favelas]. It’s not a coincidence that it’s the same paper to have created a “war editorial” section in 2017 to cover the violence in Rio. The majority of negative cover stories referred to armed violence, drug dealers, and militia members. The collapse of two buildings in the Muzema favela also gained space due to the proportion of the tragedy in which 24 people died. In the sports section, the paper opted to highlight the Board of Directors of Flamengo [soccer team], who banned the expression “Festa na favela” (Party in the favela) from its social media for being something associated with violence.

In the month of April, Extra published 14 negative stories, six of them consecutively between the 11th and 16th. The stories highlighted the charges made through a payment system by militiamen in Praça Seca, in the West Zone of Rio; residents of the favela of Manguinhos, in the North Zone, who were hit by shots from a sniper, along with the tragedy in the favela of Muzema, also in the West Zone of the city.

Violence in Rio de Janeiro, as a journalistic commodity, legitimizes the concept of the “canceled CPF” (a phrase used in support of police killings, akin to stating that someone’s Social Security Number has become defunct). Negative facts about favelas are always sellable, as readers normalize the violence.

In a 2015 essay published in Nexo, Átila Roque, director of the Ford Foundation in Brazil, synthesizes: “The segregated geography of cities, the impunity that prevails in homicides committed by police and the security policy focused on war and armed confrontation against trafficking suspends, in practice, the state of rights and installs the state of exception in certain areas of cities, signaling with a tacit authorization the execution of ‘suspicious elements.’ A perverse selectivity which renders some subjects killable, without us feeling any horror or responsibility in relation to it.”

This study developed over the last few months serves as an example to show how the lack of diversity in editorial teams influences the production of content on the favelas of Rio. In recent years, discussions about the diversity of editorial teams have gained more space.

The negative covers are products of journalists with a homogenous vision, without local experience. They result in low-quality reporting due to the lack of an internal, more realistic perspective. It is time to change.

With a journalism degree from Rio de Janeiro’s Pontifical Catholic University (PUC-Rio), Michel Silva is a Rocinha favela native, a founder of community newspaper Fala Roça, not to mention contributor to The Guardian. Most recently he founded Favela em Pauta. Michel believes that community journalism is a powerful tool for social change.