This is our latest article on the new coronavirus as it impacts Rio de Janeiro’s favelas.

Lucas Lima’s 3D printers sit beside his bed, spread over his desk and several plastic chairs. Of the ten printers at his home in the favelas of Complexo do Alemão, in Rio de Janeiro’s North Zone, he’s built seven himself. If he keeps two running for the better part of the day, Lima can produce about 10-12 face shields per day.

Lima’s looking to ramp up production as soon as possible. Six of his printers burned out in an energy surge, says the 25-year-old mechanical engineer, frustrated. “I’ve been able to fix two, so now I’ll have four printers producing. Tomorrow I’ll fix another and then I’ll build two more.”

As Complexo do Alemão deals with over one thousand suspected cases of Covid-19, local health posts find themselves critically undersupplied. With a quarter of Rio hospitals reporting insufficient supplies of personal protective equipment, Lima worries about health workers’ ability to shield themselves from infection.

“These people are on the front lines to help us in case we get infected. They are running the highest risk possible,” says Lima. “We have to help, and even more so for health workers in Alemão.”

Only months ago, Lima had gained national acclaim for developing an inexpensive 3D printer prototype as part of a university internship program. Astounded at the cost of printers on the market (up to R$17,000, or US$3,150), he began sifting through scrap shops around his neighborhood of Morro do Adeus, one of the 15 favelas that make up Complexo do Alemão. After weeks spent poring over YouTube videos and online manuals, he mounted his own machine for a fraction of the cost, christening the 3D printer ‘Maria,’ named after his mother. “I studied mechanical engineering for five years and hated it. She was the only one who put up with my complaining,” jokes Lima.

Following graduation, he drew up plans to set up his own 3D printer production center, Infill, and a tech course for Alemão youth called Maker Space. He found the perfect location at a warehouse just minutes from his home.

Then came Covid-19.

Lima pivoted, teaming up with SOS3DCovid-19, a university-based initiative of 3D printing technicians (“makers”) producing medical supplies for Rio de Janeiro’s hospitals. The task was simple: print face shields and get them to health workers in need.

For Lima, however, this meant 12-mile Uber rides to and from Rio’s Pontifical Catholic University (PUC-Rio) to pick up shield materials and drop off the finished products. “The logistics were so expensive for me, heading down to PUC, bringing the shields to them to be distributed in registered hospitals. I said to myself, I have to go to PUC, bring them the shields, come back, spend all this money, why don’t I distribute them here in the favela?”

He brought his idea to the rest of the group. “I said, listen, hospitals in the favelas are a different reality. You guys are giving these shields to hospitals right out front [of PUC], great. But in other communities, people don’t go to hospitals, they go to UPAs.” UPAs are urgent care clinics located throughout the city, and the closest option for healthcare for many favela residents. Within Brazil’s public healthcare system, they are designed to be the first line of treatment, attending to less severe patients and transferring emergency cases to hospitals. With the arrival of coronavirus, Rio’s UPAs have now found themselves overcrowded and overwhelmed.

SOS3D listened, compiling an action plan to bring face shields and other materials to UPAs, Family Health Clinics (responsible for primary care), volunteer donation projects, and the military. Lima immediately set out to attend to his neighborhood.

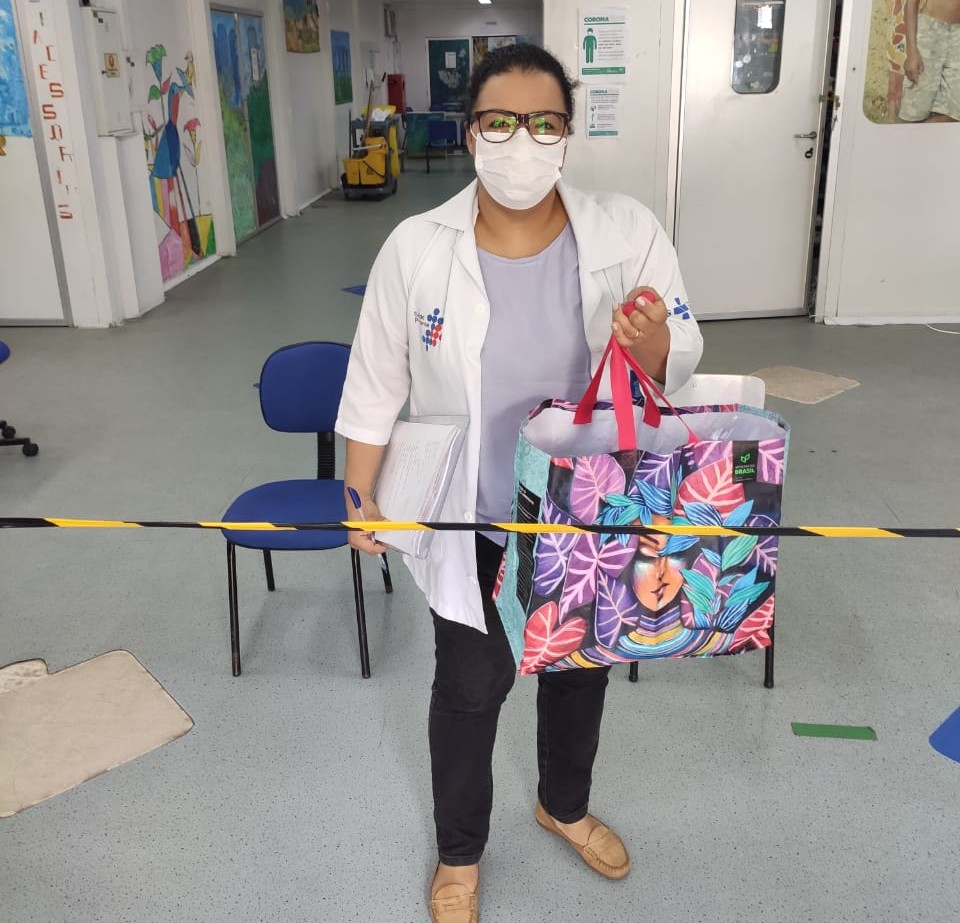

Through Rene Silva, founder of the Alemão-based favela newspaper Voz das Comunidades, Lima discovered that Alemão’s most important Family Clinic, Zilda Arns, was in desperate need of supplies. The Clinic, connected to Alemão’s central UPA, has received an average of 50-70 suspected cases of coronavirus per day. When Lima spoke to clinic manager Dr. Glauco Sousa, he realized the team had even begun running short of hand sanitizer. In addition to walking over a bag of some 30 face shields, Lima called up contacts at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), who sent over 20 liters of alcohol in gel. “He’s being an incredible partner in this moment of crisis,” Sousa told RioOnWatch.

Through Rene Silva, founder of the Alemão-based favela newspaper Voz das Comunidades, Lima discovered that Alemão’s most important Family Clinic, Zilda Arns, was in desperate need of supplies. The Clinic, connected to Alemão’s central UPA, has received an average of 50-70 suspected cases of coronavirus per day. When Lima spoke to clinic manager Dr. Glauco Sousa, he realized the team had even begun running short of hand sanitizer. In addition to walking over a bag of some 30 face shields, Lima called up contacts at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), who sent over 20 liters of alcohol in gel. “He’s being an incredible partner in this moment of crisis,” Sousa told RioOnWatch.

Lima is now looking into delivering face shields to two other health posts in Alemão, as well as to local social projects that have begun distributing food parcels and hygiene kits. Among these is the youth martial arts and personal development project Abraço Campeão. For Abraço Campeão founder and lifelong Morro do Adeus resident Alan Duarte, the face shields are perfect. “We’re going to use them this weekend in our food basket distribution,” says Duarte. “They’re going to turn us into the doctors of the alleys.”

Lima’s conception of community extends to all of Rio’s favelas. “It’s nós por nós,” (us for us) he says. “If we don’t help ourselves within the favelas, uniting the favelas, our future in a few months could be really bad.”

Days later, he trekked out to the favela of City of God in Rio’s West Zone, meeting up with Jota Marques of the City of God Front Against Coronavirus to drop off face shields for the group’s food distribution volunteers. “This is the time to come together,” says Lima. “We live in communities; we need to work in community as well.”