This article from Maré is the fifth in a series about the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on daily life in the favelas. The series is made possible through a partnership with the Behner Stiefel Center for Brazilian Studies at San Diego State University.

This article from Maré is the fifth in a series about the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on daily life in the favelas. The series is made possible through a partnership with the Behner Stiefel Center for Brazilian Studies at San Diego State University.

Disinformation and insufficient public policies demonstrate the vulnerability of Rio de Janeiro’s favelas amid the Covid-19 pandemic; local NGOs and communicators have mobilized to help families.

The Reality in the Favelas and the Need for Information

Ever since the Brazilian Ministry of Health and the World Health Organization (WHO) began issuing recommendations for the entire Brazilian population to shelter at home and respect social isolation so as to prevent the propagation of the new coronavirus, residents of favelas and the peripheries found themselves faced with massive challenges. Some of the guidelines failed to take into account the reality of favela and peripheral residents. After all, not all favelas have, for example, a regular supply of water to ensure frequent hand-washing. Another problem is the issue of crowding, since resident homes are frequently just one or two rooms per family.

Due to these factors, the scenario in the favelas is one of stark contrast with that of the upper- and middle-class areas of the city of Rio de Janeiro. Whereas in those areas, there is a lower circulation of people, in the favelas of Complexo da Maré, in the North Zone of the city, movement hasn’t stopped.

“There are many reasons for this. Children want space, and the streets are an extension of their homes. Others are forced to continue working. The situation is tough, and in times of fear and solitude we become vulnerable. Technology isn’t a replacement for human contact and chats on street corners,” explains Bira Carvalho, a photographer and resident of the Maré favela of Nova Holanda for more than 45 years.

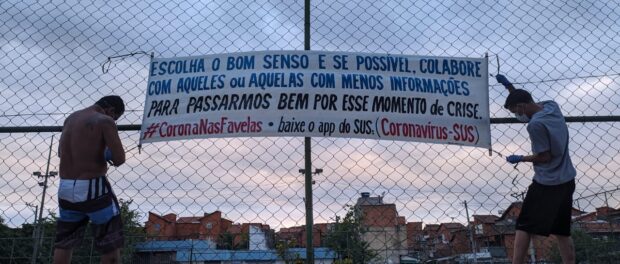

Statements by the Brazilian president, Jair Bolsonaro, and those of prominent business owners, claiming that people could resume their normal routines, in combination with a flurry of fake news, resulted in an increase in the number of residents on the streets. This further complicated efforts to raise awareness of the seriousness of the pandemic. It was thus that the population began to mistrust data released by the WHO and the Brazilian Ministry of Health, exacerbating the challenges faced by Maré grassroots communicators due to this disinformation.

In addition, a number of messages conveyed by commercial media outlets tend towards sensationalism and are not very informative. In other words, it’s not only fake news being circulated at high speeds through WhatsApp groups that needs to be combated, but also this type of content from the mainstream media. Popular communicators and favela residents from Maré realized the enormous challenge they faced and began to contemplate ways to adapt such information to the reality of the favelas.

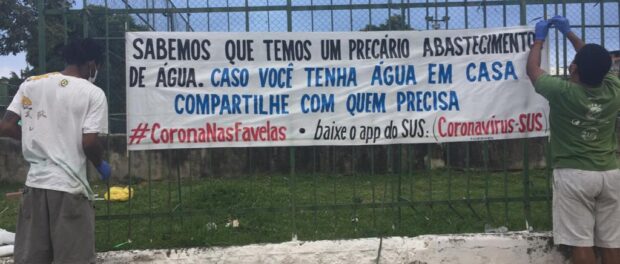

In the latter half of March, Maré communicators launched the virtual campaign “Complexo da Maré Against Coronavirus,” calling not only on Maré residents but also on those from other areas to create a communication plan that would take local factors into account. Banners, images, videos, loudspeaker-equipped cars, and signs with messages produced and approved by local health professionals have appeared throughout the streets since the last week of March.

“Another day of campaigning at businesses, bars, and churches in the favela of MARÉ!

We can’t pass out pamphlets, as that could increase the risk of infection. Instead, we are pasting fliers to the walls of areas with of high circulation.

Support community communication in the Favelas!!!!”

Public Policies to Guarantee Basic Rights

The lack of government action to address the more pressing issues prevents Maré residents from caring for their own health. Many of them still need to work to guarantee their jobs. Those who have been unable to maintain their sources of income, such as independent contractors, domestic employees, informal workers, and other groups, are unable to support their families.

After nearly a month of social isolation, the Emergency Assistance promised by Brazil’s president was first paid to those registered in Brazil’s Unified Registry (Cadastro Único). Other groups began receiving this assistance on April 14. Those who were unable to register online to receive the R$600 (US$108)—which is the case for many favela residents with no Internet access and the homeless—were instructed to visit a Caixa Econômica Federal Bank branch, resulting in a risk to their health due to the agglomerations this is generating.

There are constant water shortages and poor living conditions, while cleaning products and supplies are running out for Maré residents, as in many other Rio favelas. Once again, communicators and members of local organizations are arranging drives for basic food baskets, reporting on the difficult conditions to the mainstream media outlets, and bringing cases to the responsible authorities.

So that the number of new coronavirus cases in the favela does not increase, community leaders, communicators, and social organizations are mobilizing, but this is not enough. NGOs and social movements alone are not going to solve housing and sanitation problems, improve the health system, or resolve the financial issues of workers. Nor are these difficulties new to favela and peripheral residents, who have become even more invisible and denied their rights in the midst of the pandemic.

Public policies are needed to guarantee minimum rights to the favela population. Furthermore, government officials and the rest of society must support social movements that have been independently organizing donations of foods and cleaning supplies, in addition to working to adapt communication strategies to the local reality.

Flávia Veloso is a resident of the Águia de Ouro favela. She works as a community communicator for the Maré de Notícias newspaper and studies Journalism at Unisuam.

Gizele Martins is a Maré resident and community communicator. She holds a Master’s degree in Education, Communication, and Culture from UERJ-FEBF and a Bachelor’s degree in Journalism from the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (PUC-Rio).