This is our latest article on Covid-19 as it impacts Rio de Janeiro’s favelas.

A new study from the Data Favela research institute, a partnership between the Central Única das Favelas (CUFA) and the Instituto Locomotiva, traced the coronavirus pandemic’s widespread and negative economic impact on favelas throughout Brazil, compounding problems that have already arisen from high infection rates.

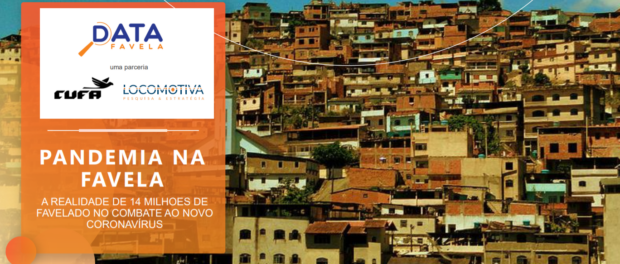

Four out of five favela families (80%) across the country are living on less than half the income they received prior to the pandemic, the study found. Of those 80%, more than a third reported losing all of their family income, while only 9% of the total experienced no change in income or only a minor drop.

During an online panel discussion about the study’s findings, Raull Santiago, co-founder of Coletivo Papo Reto, a human rights and communications collective in Complexo do Alemão and Penha favelas in Rio’s North Zone, said the pandemic was simply “exposing the historical process of exclusion” in the favelas. 76% of study respondents said they had already gone at least one day without the ability to pay for food. Two out of every three said they could only financially last one week without working. 29% said they could not last a single day.

The study was realized through 3,321 digital interviews, conducted between June 19 and 22 with residents of 239 different favelas in all 26 Brazilian states. Interviewees were chosen from a preselected sample pool in order to provide a diversity of region, age, and occupation.

The study frames its findings within the structural context of Brazilian favelas, marked by large families, high rates of cohabitation, dependence on the public health system, low levels of savings, and subpar levels of educational attainment, all of which serve to deepen the crisis.

The Challenges of Remote Learning

On top of income loss, school closings as a result of the pandemic have upped the pressure on favela families. 87% of families whose children stopped attending school have seen their household expenses increase as a result—previously, they counted on schools providing food and caring for children while parents worked. Likewise, 81% of these families reported that, as a result of having the children at home, it was more difficult to go out and work.

Favela families also reported widespread concern about the quality of education children are receiving with schools closed. Of parents with school-aged children, 84% do not believe that the home environment has been adequate for their learning and studying. “I have struggled a lot with this,” said rapper Gisele Gomes, 43, raised in the North Zone’s Brás de Pina neighborhood and better known by her artistic name Nega Gizza. With her kids at home, “I try to be a teacher, which I’m not, and it isn’t working.” This pressure is faced by mothers across Brazil.

Lack of access to computers and Internet plays a large role in these challenges. “It’s an illusion to think that remote learning will be effective with the majority of Brazilian families in the public school system,” commented sociologist Neca Setúbal. “We need high-quality Internet for everyone. It’s a right, and the pandemic shows us this very clearly.” Around 30% of Brazilian homes do not have access to the Internet, according to the Regional Studies Center for the Development of an Information Society (Centro Regional de Estudos para o Desenvolvimento da Sociedade da Informação, CETIC).

Marlova Noleto, director of UNESCO in Brazil, lamented that, inevitably, “educational inequalities will become even deeper” as a result of the crisis.

Perceptions of Coronavirus and the Challenges of Preventive Measures

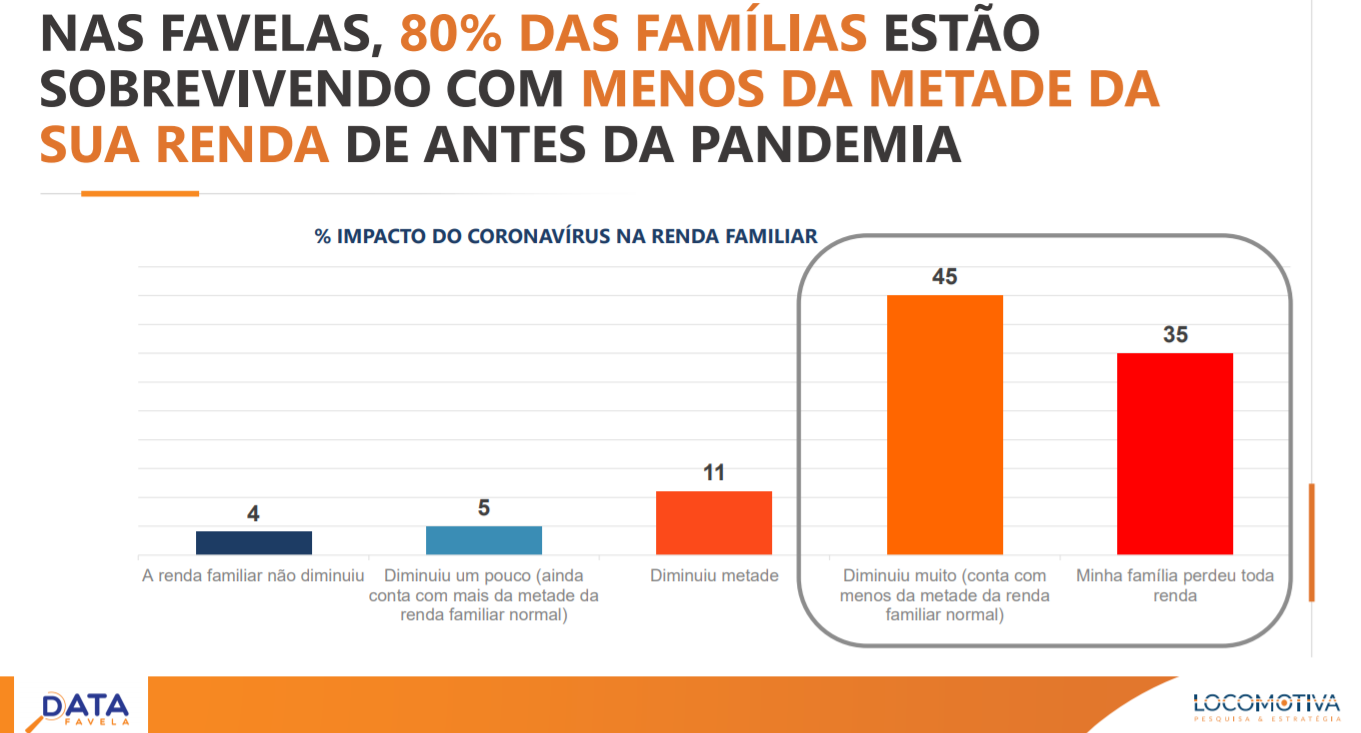

The study found that perceptions of the pandemic among favela residents vary widely. While 52% believe that Brazil is currently in the middle of the pandemic, 33% believe that the pandemic is either in its final stage, has already ended, or never existed.

However, there is much more agreement about the worry and stress that the pandemic has brought: 89% expressed concern about the health of older relatives and 88% worry about their own financial wellbeing.

80% of respondents reported that they are trying to follow physical isolation guidelines, with 39% saying that, although they try, they are not always able. Of those not following preventive measures, 72% attribute this to financial necessity. At the same time, 45% believe the measures are unnecessary, and 9%t admit to political factors in their lack of compliance. Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro has encouraged his supporters to interpret the coronavirus as a “little flu” and criticized social distancing.

Importance of Donations and Community Support

An outpouring of mutual aid in favelas in recent months prompted Renato Meirelles, founder of Instituto Locomotiva, to declare, “It isn’t the favela that has to learn from the asfalto (formal city); it’s the asfalto that has to learn from the 14 million favelados (favela residents) in Brazil.” While 49% of Brazilians have made some kind of donation during the pandemic, this number rises to 63% among favela residents, indicating greater solidarity and generosity among those who have less.

Nine out of every ten favela residents have received some form of donation, with 91% of those having received food. 69% of these donations originated from NGOs or businesses, 52% came from neighbors, friends, or relatives, and just 36% came from the government.

Although seven in ten families have signed up for emergency income support from the federal government, approved by Brazil’s Congress in April, 41% of these families have yet to receive any benefit.

“The State’s absence essentially sums up what public policy means in relation to favelas and peripheries,” pointed out Raull Santiago.

Of those who have received this assistance, 96% used it for food and 62% used it to help out friends and relatives.

The Data Favela report also highlighted the work of Mães da Favela, a program that distributes food and income support to favela mothers. Of the families who received this assistance, eight out of ten said they would have been unable to feed themselves, buy hygiene and cleaning products, or pay basic bills without the donation.

Setúbal praised the program’s focus on empowerment of mothers, lauding its achievements and saying “female leadership has a more systematic outlook” in addressing fundamental issues. “I have seen several instances in which women are taking responsibility for the caretaking of their regions, their neighborhoods. And the strength of many women, heads of their households, being able to think beyond their own families, they have taken care of their communities with their solidarity.”

Celso Athayde, CUFA’s founder, closed the study’s rollout event with an inspiring message: “Favelas aren’t a place of need, but rather of resilience and great strength.”