This is our latest article on the new coronavirus as it impacts Rio de Janeiro’s favelas and is also part of RioOnWatch’s #VoicesFromSocialMedia series, which compiles perspectives posted on social media by favela residents and activists about events and societal themes that arise.

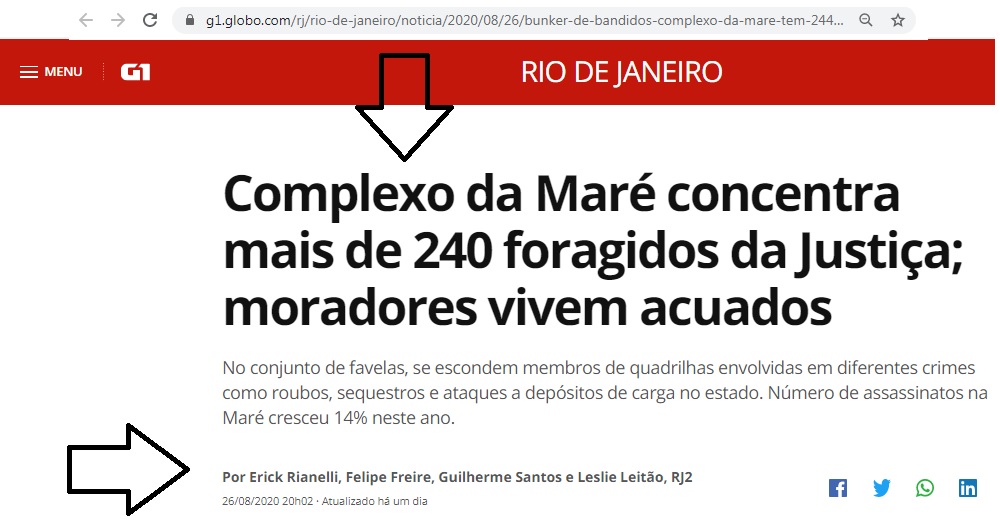

The report that aired at 6:45pm on August 26 on the news show RJ2, from TV Globo, and was reproduced by news site G1, with the original title “Bunker of criminals: Complexo da Maré has 244 fugitives from the justice system” both on the show’s website and social networks, received harsh criticism for classifying Complexo da Maré, which has 140,000 residents, as a “bunker” of criminals. Maré residents, journalists from community-based and commercial outlets, politicians, and artists protested on social media. The hashtag #MaréBunkerOfPotential (#MaréBunkerDePotência) was one of the most used on Twitter the following day, August 27.

The report that aired at 6:45pm on August 26 on the news show RJ2, from TV Globo, and was reproduced by news site G1, with the original title “Bunker of criminals: Complexo da Maré has 244 fugitives from the justice system” both on the show’s website and social networks, received harsh criticism for classifying Complexo da Maré, which has 140,000 residents, as a “bunker” of criminals. Maré residents, journalists from community-based and commercial outlets, politicians, and artists protested on social media. The hashtag #MaréBunkerOfPotential (#MaréBunkerDePotência) was one of the most used on Twitter the following day, August 27.

The report produced and researched by Erick Rianelli, Felipe Freire, Guilherme Santos and Leslie Leitão based on police investigations states: “gangs specialized in various crimes, spreading terror across Rio, in cities in the Metropolitan Region and outside the state, but with one thing in common: they have the same base, Maré.” According to the report, there are 244 fugitives living in the area.

Ei @g1rio. EU não sou bandido. Minhas amizades e familiares também não. Sou cria do Complexo do Alemão. E convivo muito na Maré. Aí fiz meu primeiro curso de comunicação comunitária. Aprendi coisas incríveis que me trazem onde me encontro hoje. Que horrível isso. Racismo puro! 🖕🏽 pic.twitter.com/gJeL2VDTh3

— Santiago, Raull #DefendaPantanal (@raullsantiago) August 27, 2020

Hey @g1rio. I am not a criminal. My friends and family aren’t either. I was raised in Complexo do Alemão. And I spend lots of time in Maré. There I did my first community communications course. I learned incredible things that brought me to where I am today. This is horrible. Pure racism!

Quoted Tweet: ‘Bunker’ of criminals, Maré Complex holds more than 240 fugitives from the justice system.

2020 e um bairro com 140 mil moradores – a maioria esmagadora sem ficha corrida – sendo chamado de “Bunker de Bandidos”. Mas o cara que tem quase 300 anos de condenação veio do Leblon. Sabe qd o Leblon receberá um rótulo desse por causa de Cabral? NUNCA. https://t.co/blLHBe0LaJ

— Cecília Olliveira (@Cecillia) August 27, 2020

2020 and a neighborhood with 140 thousand residents – the overwhelming majority without a criminal record – being called “Bunker of Criminals.” But the guy [former governor Sérgio Cabral] who has been sentenced to almost 300 years comes from Leblon [upscale neighborhood]. Do you know when Leblon will receive a label like that because of Cabral? NEVER.

Se amanhã ou depois a Maré for invadida pelas forças de segurança do estado pra que seja dada uma “resposta à sociedade”, a gente sabe quem tem a caneta cheia de sangue. Porque sua caneta pode matar, jornalista. Acorda pra vida, filho da puta.

— Marcelo D. Macedo (@mdavidmacedo) August 27, 2020

If tomorrow or later Maré is invaded by the state security forces to give a “response to society,” we know who has their pen full of blood. Because your pen can kill, journalist. Wake up to life, son of a b**ch.

Não vamos aceitar que o discurso antirracista esteja presente somente nas palavras. Mais uma vez, um dos grandes veículos de comunicação no Brasil disseminou preconceito e ignorância contra uma das maiores favelas do país. #MaréBunkerDePotência pic.twitter.com/SOY7oPuutk

— Movimentos – Drogas, Juventude & Favela (@movimentos_) August 27, 2020

We’re not going to accept that antiracist discourse be present only in words. Once again, one of the biggest communication outlets in Brazil disseminated prejudice and ignorance against one of the largest favelas in the country. #MaréBunkerOfPotential

G1 Changes Headline, But Does Not Contain the Wave #MaréOfPotential

The repercussion and reach of the criticisms was so great that G1, on the same day, at 8:02pm, changed the headline of the article to: “Complexo da Maré has over 240 fugitives from the justice system; residents cornered.” However, in the report’s link, its original title which qualified Maré as a “bunker of criminals” was still visible.

The G1 news portal also deleted the Twitter post of the report with the first “headline.”

G1 apagou o tuíte gente…

— Edmund Ruge (@EdmundRuge) August 27, 2020

G1 deleted the tweet people…

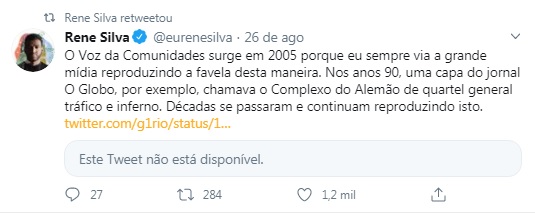

But several posts with criticism, which shared G1’s original tweet, left a trail in an attempt to manage the crisis: “This Tweet is not available,” as we can see in the post by founder of community newspaper Voz das Comunidades, Rene Silva.

But several posts with criticism, which shared G1’s original tweet, left a trail in an attempt to manage the crisis: “This Tweet is not available,” as we can see in the post by founder of community newspaper Voz das Comunidades, Rene Silva.

Voz das Comunidades emerged in 2005 because I always saw mainstream media representing the favela in this way. In the 1990s, a cover of the newspaper O Globo, for example, called Complexo do Alemão the headquarters of drug trafficking and hell. Decades pass by and they continue reproducing this.

However, in the age of digital journalism, according to a report about digital news from the Reuters Institute for Journalism Studies at the University of Oxford, access to news primarily occurs on mobile phones. According to data collected by Google in 2019, 70% of Brazilians use smartphones to read news. With this, it is simple to “take a screenshot,” and pass along these images, which was done en masse in spite of G1’s deletion of the publication. Images of the original article began to circulate on the Internet and were the main image of the voices from the favelas on social networks opposing the criminalizing discourse of the report.

However, in the age of digital journalism, according to a report about digital news from the Reuters Institute for Journalism Studies at the University of Oxford, access to news primarily occurs on mobile phones. According to data collected by Google in 2019, 70% of Brazilians use smartphones to read news. With this, it is simple to “take a screenshot,” and pass along these images, which was done en masse in spite of G1’s deletion of the publication. Images of the original article began to circulate on the Internet and were the main image of the voices from the favelas on social networks opposing the criminalizing discourse of the report.

A maior apreensão de armas pela polícia não foi em uma favela. A maior apreensão de drogas também não.

Ainda assim, a grande mídia insiste em reduzir o nosso território à criminalidade. Favela tem mais arte que crime. Favela tem mais empreendimentos que crime.

— Rennan Leta (@rennanleta) August 27, 2020

The biggest apprehension of arms by the police was not in a favela. Neither was the biggest apprehension of drugs. Still, mainstream media insists on reducing our territory to criminality. Favelas have more art than crime. Favelas have more businesses than crime.

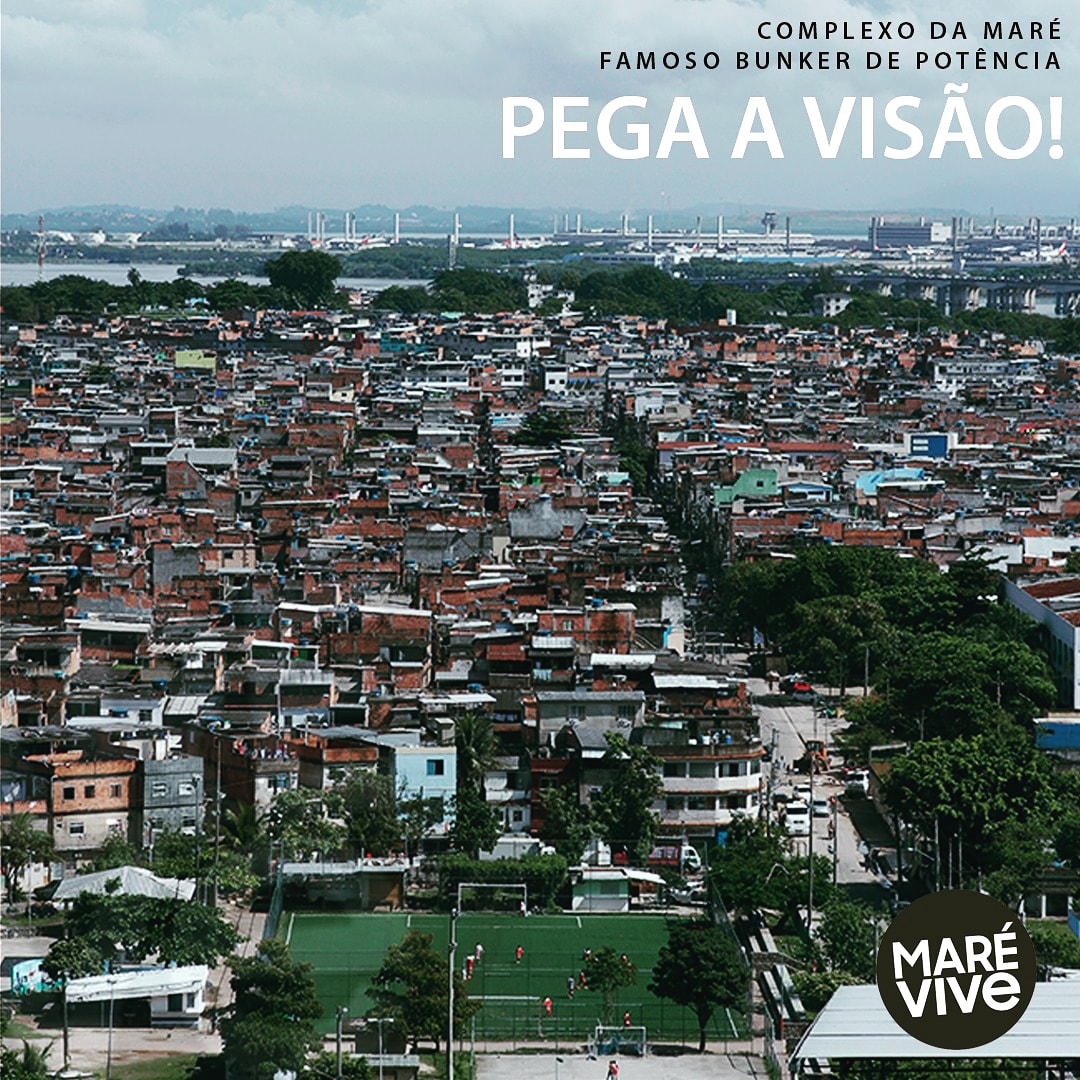

Using the hashtag #MaréBunkerOfPotential (#MaréBunkerDePotência), the Marielle Franco Institute as well as other community communicators, journalists, social movements, black intellectuals, artists, politicians and Maré residents began to tell the story of the potential of Maré, provoking the debate and dispute of narratives on social networks.

E se a gente listasse junto aqui todos os projetos, pessoas e ideias da Maré para mostrar que a favela é na verdade bunker de POTÊNCIA? Marca aí! Quem você conhece?

A gente começa: Quer mais potência que Marielle Franco, cria da Maré? #MaréBunkerDePotência pic.twitter.com/W3Qz4tNXst

— Instituto Marielle Franco (@inst_marielle) August 27, 2020

And if we listed here together all of the projects, people, and ideas to come out of Maré to show that the favela is really a bunker of POTENTIAL? Leave them here! Who do you know? We’ll start: Do you want more potential than Marielle Franco, raised in Maré? #MaréBunkerOfPotential

Na maré tem economista @athaisdejesus

Na maré tem comunicador e jornalista @giz_omartins @eunaldinho

Na maré tem analista em relações internacionais e video maker @MayDonaria

Na maré tem povo que (sobre)vive, que luta, que constrói essa cidade.#MaréBunkerDePotência— Marcelle Decothé (@marcelledecothe) August 27, 2020

In Maré, there is the economist @athaisdejesus

In Maré, there are communicators and journalists @giz_omartins @eunaldinho

In Maré, there is international relations analyst and video maker @MayDonaria

In Maré, there is a people who survive, struggle, and build this city. #MaréBunkerOfPotential

Muito orgulho de onde eu vim.

Prazer, sou cria da Maré.

Também conhecida como Bunker de Potência.

#MareBunkerDePotencia pic.twitter.com/RR1x5d6RGR

— Raife Salles (@Raife_Sales) August 27, 2020

Very proud of where I come from.

Pleasure to meet you, I was raised in Maré.

Also known as Bunker of Potential.

#MaréBunkerOfPotential

Vcs sabem que ganhamos esse festival no ano passado? #MareBunkerDePotencia #MareBunkerDeArtistas https://t.co/FVkB9LWiwL

— #LendoJunto📚 no Quilombo Moderno (@quilombomodern) August 27, 2020

Do you guys know that we won this festival last year?

#MaréBunkerOfPotential

#MaréBunkerOfArtistsQuoted Tweet: #MaréBunkerOfPotential #MaréBunkerofArtists Last year we won the National Festival of University Theater, in its 9th edition. Year 2019. With the skit “NOT EVERY CHILD AVENGES!” Company Raised in the Alley. Maré won, we are Maré!

Absurdo de linguagem e preconceito. Atenção @g1rio A Maré é a casa de milhares de brasileiras e brasileiros que lutam pra fazer do Rio de Janeiro uma cidade melhor #MareBunkerDePotencia pic.twitter.com/9zvdJ0k6pg

— Jurema Werneck (@juremawerneck) August 27, 2020

Absurd language and prejudice. Attention @g1rio Maré is the home of thousands of Brazilians that struggle to make Rio de Janeiro a better city #MaréBunkerOfPotential

In an article published in the newspaper Brasil de Fato, the popular journalist and communicator Gizele Martins, who holds a Master’s in Communication, Education and Culture in Urban Peripheries (FEBF-UERJ), is a member of the Favela Movement of Rio de Janeiro, and is a resident of Maré, says: “We are a ‘bunker’ of solidarity, leisure, culture, work, studies, community life and community communication,” and adds that Maré “came out last Wednesday in several media outlets, but unfortunately the actions of solidarity in this time of the pandemic were not reported. One of them is the work of the Maré Mobilization Front, which now serves more than 3,000 families a month with food donations, in addition to the entire favela producing communication about Covid-19. The media also left no mention of the historic and important space of community and favela memory that is the Maré Museum, the first museum built inside a favela in the world.”

Community Media

Maré, located in the North Zone, is made up of 16 favelas and is the largest complex of favelas in the city. It was officially recognized as a neighborhood of Rio de Janeiro in 1994. People born in Maré are called Mareense, a term coined by the newspaper The Citizen, a local community outlet that has existed for over 20 years. The archipelago of nine islands in Guanabara Bay where fishermen lived for more than 8,000 years began to form the favelas of Maré in the 1940s with the expansion of the city and the construction of the university campus of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), on the island of Fundão.

Brota na pista q hj é sexta bb e o “bunker de trabalhador da Maré” já tá colocando seu bloco na rua, pegou a visão @g1? Os Mareenses q não estão na labuta, estão procurando um modo de se reinventar com novas formas de trabalho, tem um bonde se ligou mídia comédia? >>> pic.twitter.com/eyAc0jHtGM

— Maré Vive (@MareVive) August 28, 2020

Bloom from the street because today is Friday, baby, and the “bunker of the Maré worker” is already putting his parade in the street, you get the picture @g1? The Mareenses that aren’t at their jobs are looking for a way to reinvent themselves with new ways of work, is there a group that has linked media and comedy?

Maré’s group of favelas is known internationally. It is the origin and home of initiatives of art, audiovisual production, theater companies, entrepreneurs, intellectuals, photographers, filmmakers and human rights activism. It has strong community media, with The Citizen, Maré de Notícias, Maré Vive, and the international journal Peripheries, among other local outlets, and observatories of critical social analysis such as the Favelas Observatory, the João Maria Aleixo Institute and data_labe (a laboratory of data production and narratives). There is also one of the most important and original college exam preparatory courses, CEASM, an NGO that just turned 23, where intellectuals such as Marielle Franco, Renata Souza, and Gizele Martins have studied—along with so many other Mareenses who could access higher education through the course—in addition to several other workers of various professions, without or with formal education.

#MareBunkerDePotencia #Mare https://t.co/b1raTmWBrs

— Miriane Peregrino (@mirianescreve) August 27, 2020

#MareBunkerOfPotential+55 61 9575-9339 #Mare

Quoted Tweet: READ: #emergencydiaries #covid19

Matheus Frazão is raised in the Maré favela. Actor, Art Educator at the Maré Museum, and facilitator of the Theater Extension Program in Communities. He is the son of Joana D’arc and Marcos Antonio. To whoever it may interest, he is a Taurus.

Naldinho, fotógrafo da Maré, relembrou outro dia de Marielle, que tinha até “Maré” no nome. #MareBunkerDePotencia https://t.co/Czv07LWm4e

— rafucko (@rafucko) August 27, 2020

Naldinho, the photographer from Maré, reminded me the other day of Marielle, who even had “Maré” in her name. #MaréBunkerOfPotential

Quoted tweet: That selfie with a taste of longing. Good Day!

As favelas são potência e a comunicação comunitária e as lideranças locais estão há anos desenvolvendo projetos e conteúdo que a mídia tradicional insiste em ignorar. O nosso papel é justamente mostrar as potencialidades do nosso território. 👇#MareBunkerDePotencia

— Maré de Notícias (@MareNoticias) August 27, 2020

The favelas are potent and their community communicators and local leaders have for years been developing projects and content that the traditional media insists on ignoring. Our role is precisely to show the potential of our territory. #MaréBunkerOfPotential

Maré’s community-based production is a reference for other favelas, journalists, and community communicators in Rio de Janeiro and across the country. Among them, the newspaper Fala Roça, from Rocinha, which also published criticism of the stigma against favelas and their residents built over years by commercial media:

Errar 1x pode ser descuido. Errar todas as vezes é projeto. Afinal, a quem interessa que a nossa população não seja empoderada, consciente, plena de seus direitos?#MareBunkerDePotencia pic.twitter.com/BHqAOZGQdM

— Fala Roça (@jornalfalaroca) August 27, 2020

Making a mistake one time could be carelessness. Making a mistake every time is a project. After all, who does it benefit when our population is not empowered, aware, and fully exercising their rights?

Because of the hashtag #MaréBunkerOfPotential, social networks also highlighted how the criminalization of favelas by traditional journalism is done through the discourse of violence, and how this production of narratives harms life on a daily basis for communities, even having the power to hinder community journalism.

Após a denúncia do RJTV“BunkerDaMaré” mandando produtores vim compra drogas pra tirar fotos dos traficantes,

compromete mt nosso trabalho local, pq nós não se sentimos a vontade de andar com uma câmera pela nossa favela… #MaréBunkerDePotência— josé (@bismarcck_) August 27, 2020

After the complaint about RJTV “BunkerOfMaré” sending producers to come buy drugs to take pictures of traffickers, it greatly compromises our own local work, because we don’t feel comfortable walking with a camera through our favela…

#MaréBunkerOfPotential

Although the G1 portal changed the name of the article, the production, editing and content of the report remains in tact. In this context, other voices on social networks recalled that the way the report was conducted—the treatment given to the information and coverage—is not a mistake, but a common, prejudiced practice of the media when reporting news of violence. This reveals community communication as a place of representation of voices from the favelas, peripheries and workers in general.

O rapaz de classe média que TRAFICAVA animais sistematicamente foi chamado “estudante”, diminuindo a gravidade do fato dele TRAFICAR ANIMAIS. Aí na Maré é “Bunker de Bandido”?????? Pera lá!

ENTENDAM A IMPORTÂNCIA DO JORNALISMO COMUNITÁRIO #MaréBunkerDePotência

— wyllian torres 🏳️🌈 (@wylltorres) August 27, 2020

The middle-class guy who TRAFFICKED animals systematically was called a “student,” diminishing the gravity of the fact that he TRAFFICKED ANIMALS. Over there in Maré it’s “Bunker of Criminals”????? Stop right there!

UNDERSTAND THE IMPORTANCE OF COMMUNITY JOURNALISM #MaréBunkerOfPotential

Falar que a Maré é Bunker de bandido explica muito sobre:

1- Quem fala.

2-Discurso é disputa.

3-Como nessa cidade o seu valor é definido pelo seu CEP.#MareBunkerDePotencia— Gabriella Maria (@marygabis) August 27, 2020

To say that Maré is a Bunker of criminals explains a lot about:

1- Who speaks.

2- Discourse is dispute.

3- How in this city your worth is defined by your post code. #MaréBunkerOfPotential

A MARÉ NÃO É BUNKER DE BANDIDO, como afirmou ontem a mídia comercial.

NÓS SOMOS BUNKER DE COMUNICAÇÃO COMUNITÁRIA, DE SOLIDARIEDADE, DE LUTA!#MaréBunkerDePotência— Gizele Martins (@giz_omartins) August 27, 2020

MARÉ IS NOT A BUNKER OF CRIMINALS, like the commercial media affirmed yesterday. WE ARE A BUNKER OF COMMUNITY COMMUNICATION, OF SOLIDARITY, OF STRUGGLE! #MaréBunkerOfPotential

Maré Mobilization Front

In the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, unsupported and neglected by the state, it was Maré residents who organized to minimize the effects of the crisis generated by the pandemic, serving more than 3,000 families per month with food donations. The Maré Mobilization Front began on March 19th and brings together 14 organizations: Maré 0800, Maré Vive, Casulo, Roça Rio, CEASM, Maré Museum, ONG Pra Elas, RatoPretoStudio, Agência LABirinto, Ativa Breakers Crew, Podcast Renegadus, CEC Orosina Vieira, Yoga na Maré, Roda Cultural do Parque União, adding up to an estimated 100 committed residents.

A Maré é uma favela que resiste desde sempre a negligência do Estado. Lugar de verdadeiras potências que lutam diariamente pra trazer a dignidade que o Estado não traz.

A Frente Maré é uma dessas potências.Foto: @commarinhoo #MaréBunkerdePotência pic.twitter.com/HgQJvuf4rT

— Frente Maré (@FrenteMare) August 27, 2020

Maré is a favela that has always resisted state neglect. Place of true potentials that struggle daily to bring dignity that the State doesn’t bring. The Maré Front is one of those potentials. Photo: @commarinho #MaréBunkerOfPotential

Maré has a population larger than 93% of Brazilian municipalities, with one of the largest numbers of collectives and networks. Maré is big. There are many Marés within Maré. In the absence of reliable official public data on the Covid-19 pandemic, in fact, the work of these local networks stands out for its role in data collection, as can be seen in the Covid-19 in Favelas Unified Dashboard.* According to the Dashboards’s latest release: “until now, the favelas with the most precise counts are the 16 favelas that make up the Complexo da Maré… and five communities in neighboring municipality of Itaguaí.” Counting in Maré, carried out by Redes da Maré, is yet another example of how community action is saving lives and producing solutions, in the absence of the State in prevention, mitigation, and public investment.

Quando tinha 15 anos, participei do Censo da Maré, ajudando a colocar a minha favela no mapa da nossa cidade. Andei toda comunidade, entrei em cada beco e viela, conversei com centenas de famílias, me descobri como mareense! A Maré não é bunker de bandido, é #MaréBunkerDePotência https://t.co/PF9ZEj8hE2

— Renata Souza (@renatasouzario) August 27, 2020

When I was 15 years old, I participated in the Maré Census, helping put my favela on the map of our city. I walked every community, entered every alley and lane, talked with hundreds of families, I discovered myself as a Mareense! Maré isn’t a bunker of criminals, it’s #MaréBunkerOfPotential

Quoted tweet: Maré is a bunker, yes. But of potential.

#MaréBunkerOfPotential

Of the Observatory @defavelas

Of Marielle Franco and of @aniellefranco, of @inst_marielle

Of @brenolaerte, of @renatasouzario, of @tcavalcantes, of @adrianumendes, of @nega_samurai and of another group of potentials.

A Maré, como o próprio nome sugere, é potência! Não cabe no estigma que tentam nos impor. Não aceitaremos generalizações negativas na mídia. O papel da imprensa não é corroborar com a ausência do Estado e marginalizar milhares de famílias. Chega! #MaréBunkerDePotência

— Monica Benicio (@monica_benicio) August 27, 2020

Maré, just like the name itself suggests, is potential! It doesn’t fit the stigma that they try to impose on us. We will not accept negative generalizations in the media. The role of the press is not to corroborate the absence of the state and to marginalize thousands of families. Enough! #MaréBunkerOfPotential

Throughout the day on August 26, news programs and journalistic websites, in various articles, questioned why the police were not entering the favelas to contain crimes. Two months ago, the Supreme Court approved a lawsuit called a Claim of Noncompliance of a Fundamental Order (ADPF), which now restricts police operations in the favelas due to the pandemic. With the measure, there was a 76% drop in the number of deaths and injuries in Rio de Janeiro in the last two months.

Monitoring of social networks brings to light how the report made a journalistic clipping in which only a single “side” of Maré is shown, generalizing the entire territory of the 16 favelas as a shelter for crime, reducing the agency and potential of a population of more than 140,000 residents to a group of “244 fugitives.” The article goes on to say that “the Civil Police says that they are a small part of thousands of criminals who control the 16 favelas of Maré,” while they do not say that they are a tiny part (.01%) of the population of Maré, a population, as seen by the reports above, that carries out plans and is full of potential for our city.

It reduces tens of thousands of Maré voices to the voice of the police and crime: “They are, according to the police, groups specialized in car thefts in the South Zone, lightning kidnappings in the North Zone, responsible for attacks on storage units in the Baixada Fluminense and bank robberies in São Gonçalo, in the Metropolitan Region. The actions take place even outside the state, in Minas Gerais”, say RJ2 and G1.

Although the report narrating the organization of a network of criminal groups that, according to the report and the Civil Police, are sheltered in Maré, the article does not mention or question how this network has access to their amount of weapons, an “arsenal of war,” or how this arsenal reaches the favelas.

Gizele Martins says, “The commercial media, historically, in this country, have shamelessly described favela residents, their territories, their customs, their culture, their music, their speeches, the color of their skin always with the intention to criminalize, marginalize, violate and inferiorize all those who live in these places that are impoverished and inhabited by a majority black population.”

Gizele Martins says, “The commercial media, historically, in this country, have shamelessly described favela residents, their territories, their customs, their culture, their music, their speeches, the color of their skin always with the intention to criminalize, marginalize, violate and inferiorize all those who live in these places that are impoverished and inhabited by a majority black population.”

The use of the word “bunker” in news articles about violence related to favelas is common, as can be seen in a Google search. Searching for “bunker of trafficking” yields various news articles, videos, and images such as the cover of O Globo newspaper from November 25, 2010, at the time of the occupation of the Penha favela complex. According to the Houaiss dictionary, “bunker” is a masculine noun that means “fortified structure or stronghold, partially or totally underground, built to withstand the projectiles of war,” meaning “very protected shelter.”

Tony Marlon, columnist for news site Uol, in a column published on August 28, says, “When you say that the home of many is a ‘bunker of criminals,’ it creates an idea that it is necessary to put an end to that place, and everything that fits in it, because only then society will be safe. Will you restore the life of a son or daughter when a mother is crying over her death for being simply someone who lives where she lives?”

*The Covid-19 in Favelas Unified dashboard and RioOnWatch are both projects of the NGO Catalytic Communities (CatComm).