This is our latest article on Covid-19 and its impacts on favelas and is also part of our reporting partnership with The Rio Times. For the article as published in The Rio Times click here.

It is the peak of the pandemic in Brazil, and the immediacy of water shortages in favelas remains dire. Facing a continued lack of essential supplies and public services to fight the daily battle against Covid-19, civil society groups have risen to the occasion. The government, on the other hand, has focused its energy on a controversial 35-year plan to contract out the operations of state water utility CEDAE in partnership with Brazil’s national development bank BNDES.

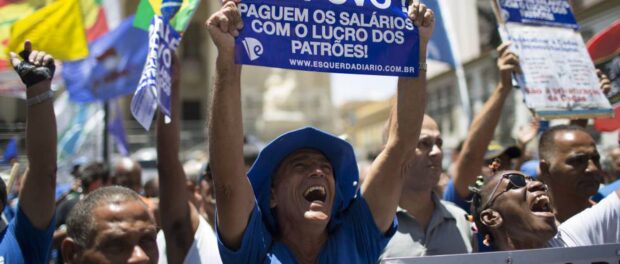

On June 24, Brazil’s Senate gave Rio’s government the go-ahead to privatize CEDAE via the revised Basic Sanitation Regulatory Framework (PL 4.162/2019) passed by the Chamber of Deputies in December. In response, Rio’s government eagerly launched its plans, holding the first in a series of three virtual public hearings on the procedures for contracting out CEDAE’s operations just one day later. Many people at the hearing voiced strong doubts about the government’s claims that this process will result in universalized collection, treatment, and supply of water throughout the state and billions in economic gain for the city. Anti-privatization protests and heated debate on the matter, present since talk of privatization emerged after the 2016 Rio Olympics, have increased in their vigor.

The plan to grant private concessions for CEDAE’s operations involves splitting Rio’s municipalities into four blocks—a strategy which aims to combine wealthier regions with those that severely lack basic sanitation infrastructure. While this plan may encourage private investment in otherwise “unlucrative” communities, some believe that it will subject citizens in the peripheries to exorbitant costs. Currently, 6% of Rio’s water is operated by private companies, and residents living in these regions pay up to 70% more for their water than do those serviced by CEDAE.

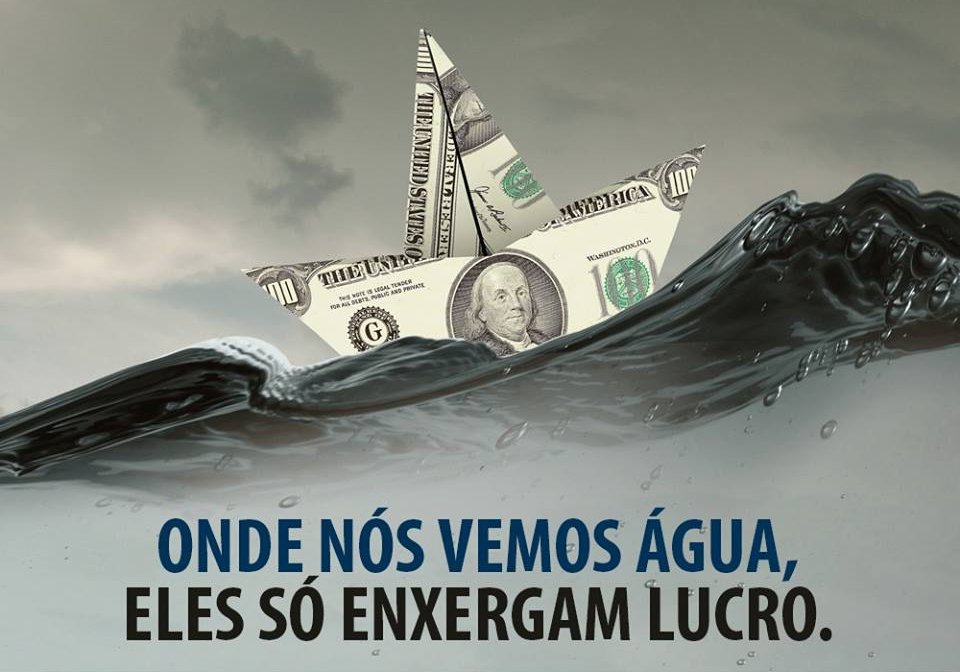

Corporate Accountability International’s 2014 research on the case for public water found that the relative efficiencies of public and private water companies were comparable. Meanwhile, the economic incentive structure of private competition in the water market is known to increase inequality. Private water companies are incentivized to prioritize their shareholders and their own profitability over a mandate to prove quality service at reasonable rates for under-resourced communities. When private water companies act as monopolies, they tend to set the price of their services low at the beginning of their contracts, only then to exorbitantly increase those prices. This, as a consequence, ends up costing taxpayers more in the long run.

In the first public hearing, BNDES president Guilherme da Rocha Albuquerque attempted to quell concerns about who eventually will foot the bill for this shift. He said that “the civil population will not have to pay more for the [sanitation] services” despite the fact that the private sector is projected to take over R$33.5 billion (US$5.95 billion) of operations from CEDAE. Questioning this conclusion, doctoral student and geography professor Danilo Cerqueira asked, “If the companies are going to invest billions in sanitation, who is going to pay? The populations who don’t have access to sanitation or water supply are the poorest people in our state, living in the periphery.” Others present at the hearing echoed the fear that higher tariffs would be imposed on those with precarious water and sanitation access—the same individuals whose struggle to afford basic necessities has intensified during the pandemic.

Rio’s Budgetary Crisis Examined

The state of Rio is in deep debt, owing R$4.5 billion (US$810 million) to the federal government. Historically, the federal government has come to its rescue, although not without strings attached. In 2016, the federal government created a Fiscal Recovery Plan which gave the state until January 2021 to repay its debt under the condition that it privatize CEDAE as well as adopt austerity measures. As it has in the past, Rio has turned to the prospect of water privatization with hopes of attracting investment to help service its debt. According to governor Wilson Witzel, who has currently been suspended as corruption investigations proceed against him, selling CEDAE’s operations may earn Rio up to R$20 billion (almost US$4 billion).

Nonetheless, the opponents of privatization argue that CEDAE is already a fairly lucrative company for the government, and that selling it would not generate the revenue that officials predict. Former CEDAE president Wagner Victer said in a recent interview that if CEDAE remains a public company, it will earn around the equivalent of R$20 billion over the next 17 years.

Multiple factors precipitated Rio’s current debt crisis. The notoriously expensive 2016 Olympics cost the city over $13 billion, with a significant chunk of these funds spent on since-abandoned Olympic venues and disproportionately invested in the upper class. Before the Games, Mayor Eduardo Paes promised to have all of Rio’s favelas urbanized by 2020; instead, thousands of people were displaced during pre-Olympic construction. The state dished out $3.1 billion for an expansion of the subway system, boasting that it would radically transform Rio’s transportation network, but the extension from Barra de Tijuca to Ipanema links only Rio’s wealthiest neighborhoods.

Rio has long relied on royalties from oil exploration to finance its expenses. State-run oil company Petrobras has suffered from sharply declining international petroleum prices in 2020, which it calls “the worst crisis in the petroleum industry in the last 100 years.” In tandem with this marketwide downturn, a federal law passed in 2012 reduced the petroleum revenue that Rio and other states could collect from 26.25% of companies’ net earnings down to 20%. As a result, the National Petroleum Agency has predicted that Rio will lose R$56 billion (US$10 billion) over the next three years.

While most people agree that Rio must take action to ameliorate its immediate budgetary crisis, the decision to use CEDAE for this purpose is highly contentious. Ana Lucia Britto, an urban studies professor at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, criticized the decision at the virtual event “Transforming Basic Sanitation in the Favelas after the Pandemic,” hosted by the Sustainable Favela Network (SFN)*. “Using a public company to pay state debt is absurd,” Britto said. She hinted that the situation would be better resolved by first addressing the misallocation of funds: “The local government receives money every month and nobody knows where this money goes. If the local government is responsible for sewage in the favelas, it should be using this money for this purpose; instead, it goes to the city’s general budget.”

Irenaldo Honório, the former president of the Pica-Pau Residents’ Association and a committed sanitation activist, addressed how rampant government corruption has contributed to Rio’s massive debt. “In reality, CEDAE should not be sold to cover the expenses that the previous governor [Sérgio Cabral], who is now in prison, left. His assets have to be paid for, and the debt he created, too,” Honório said. As he sees it, the government must “give the money [Cabral] stole back to the public, and not privatize CEDAE for an error not made by us, but rather by the governor himself.”

Why Now?

Many are asking why governor Witzel has chosen the peak of the Covid-19 pandemic to privatize CEDAE, as the discussion has been on the table for years now. During the first public hearing, environmental activist Mayara Horta Yeager pointed out that debating the concession during the pandemic means it is more difficult for a diverse range of groups to participate in the discussion. “We have to increase participation from public institutions, federal universities which monitor water quality, and also from the population most affected by sanitation issues in the metropolitan region of Rio de Janeiro,” Yeager said. Britto stressed that the virtual public hearing model inherently excludes favela voices, undermining communication rights: “How can you discuss a matter that is going to affect the lives of so many people with audiences that aren’t decentralized and in-person? Favela residents don’t have internet access.”

It is precisely the distracting political moment, however, on which some believe the government is capitalizing. Water privatization, after all, is a decreasing trend: over 90% of water services are publicly provided throughout the world today. Cities across the globe that once chose to sell their publicly owned water companies to the private sector have since undergone remunicipalisation—returning water assets back to state ownership. Bringing awareness to this fact, social media campaigns such as #naoàprivatizaçãodaágua (#notowaterprivatization) argue that privatizing a basic good like water is not only inefficient and costly but is also a human rights violation.

Though some argue today that privatization can fix inefficiencies at CEDAE, that was not the original reason behind the legislation that makes it possible. Rio’s State Legislative Assembly changed the state’s constitution in 2016 to allow for privatization in order to generate funds to help repay state debt. The discussion at the time had little—if anything—to do with the company being inefficient. Historically, despite deficient service in Greater Rio de Janeiro’s Baixada Fluminense region, CEDAE has successfully met the federal government’s standards and requirements. It has provided water for two million people. It was only more recently that the government began to encourage the narrative that CEDAE was failing.

At the beginning of January, murky and smelly water caused outrage among Rio’s citizens. Although CEDAE claimed that the water was safe to drink—as the color and smell were purportedly caused by geosmin, a natural algae-born substance—the city saw widespread gastrointestinal hospital visits in the weeks that followed. In August, Data_Labe, a data journalism group based in Complexo da Maré, published an article about the possible effects of water privatization on Rio’s favelas which cited a study that found the water was significantly contaminated with both domestic sewage and industrial pollution. Given that the water quality suddenly deteriorated around the time that talk of privatizing CEDAE was on the rise, many people believe that the water crisis was an intentional disturbance of public order. Witzel addressed such suspicions in a public statement, denying responsibility for meddling in the crisis. “I suspect that there was sabotage, exactly to undermine CEDAE’s efficient management that is underway as it prepares for the auction,” Witzel said. A police investigation into the allegations of sabotage was opened and then closed due to insufficient evidence.

Members of the political left have accused Witzel and his government of sabotaging the water system to make CEDAE appear inefficient and to justify its replacement. In their view, the sabotage extends to mass layoffs of CEDAE employees. Humberto Lemos, the president of sanitation workers’ union Sinstama-RJ, said in a January interview that government officials conduct sabotage “when they lay off technical workers and trained engineers. They put a thousand people out of work via the PDV [Voluntary Resignation Program].” In May, the situation became even more grave when CEDAE president Renato Espírito Santo announced plans to lay off 80% of company workers after auctioning CEDAE’s operations off to private corporations.

To be sure, Rio’s water system needs dramatic improvements. Rio’s famous Guanabara Bay is heavily polluted—over one billion liters of sewage runoff flow into rivers that empty into the bay each day. Furthermore, sanitation NGO Trata Brasil Institute estimates that only 42.9% of the sewage generated in Rio de Janeiro is treated. At the July 6 public hearing, Trata Brasil’s president, Edison Carlos, lamented the extremely poor condition of Rio’s water system, blaming the government for its its mismanagement. “In eight years, we haven’t seen any advancement in water treatment…the regulation needs to be rigorous…We are tired of promises,” he said. As he sees it, “Rio de Janeiro has great potential…if it seriously invests in sanitation treatment.” Carlos believes that the best method to generate this investment is through the privatization of CEDAE.

To be sure, Rio’s water system needs dramatic improvements. Rio’s famous Guanabara Bay is heavily polluted—over one billion liters of sewage runoff flow into rivers that empty into the bay each day. Furthermore, sanitation NGO Trata Brasil Institute estimates that only 42.9% of the sewage generated in Rio de Janeiro is treated. At the July 6 public hearing, Trata Brasil’s president, Edison Carlos, lamented the extremely poor condition of Rio’s water system, blaming the government for its its mismanagement. “In eight years, we haven’t seen any advancement in water treatment…the regulation needs to be rigorous…We are tired of promises,” he said. As he sees it, “Rio de Janeiro has great potential…if it seriously invests in sanitation treatment.” Carlos believes that the best method to generate this investment is through the privatization of CEDAE.

For economist Marco Antonio Rocha of the University of Campinas, the government’s failure to provide clean and adequate water to all citizens is due to a lack of political will rather than a lack of state capacity. In a June interview, he said that Rio’s government has more than enough money to provide satisfactory water and sanitation services but has refused to appropriately allocate the funds. Rocha argued that the solution is to make universal basic sanitation a political imperative, and said that “as healthcare is teaching us, to make a service universal, it has to be public.”

While the privatization debate rages on, the voices of favela residents who continue to suffer from poor sanitation and a lack of water continue to be excluded. “The favelas were disregarded in the city plan,” researcher Alexandre Pessoa said at the SFN event. “That is environmental racism. That is state violence.”

“The pandemic shined a light on the sanitation situation in the favelas,” said Britto. After decades of government neglect and amid lack of access to full water and sanitation during the crisis, favela residents were left to create their own solutions, evidencing, for Pessoa, how “community organization is fundamental to basic sanitation.”

*The Sustainable Favela Network and RioOnWatch are projects of the NGO Catalytic Communities (CatComm).