This is our most recent article in a series created in partnership with the Behner Stiefel Center for Brazilian Studies at San Diego State University, to produce articles for the Digital Brazil Project on human rights and socio-environmental justice in the favelas for RioOnWatch.

This is our most recent article in a series created in partnership with the Behner Stiefel Center for Brazilian Studies at San Diego State University, to produce articles for the Digital Brazil Project on human rights and socio-environmental justice in the favelas for RioOnWatch.

The voices of Vila Kennedy favela, in Rio’s West Zone, and of many other communities from across the city, came together to mourn the loss of Fabiano Veloso, better known as Ravengard or Raven. He was a deep and always accessible fountain of knowledge as a horticultural activist and member of the Urban Food Movement in Vila Kennedy—known by its acronym in Portuguese MUDA VK, which in Portuguese also means “Change Vila Kennedy” or “Vila Kennedy Seedling” as the word “muda” means both change and seedling.

Ravengard invented a highly productive “Instant Substrate” and taught widely on its application to urban gardening. He was part of Rio’s Sustainable Favela Network (SFN), active in both its Solid Waste Working Group and Gardens and Reforestation Working Group. And for many years he was affiliated with the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), undertaking green initiatives connecting academia to grassroots change. Educator, actor, teacher, director, producer, environmentalist, and activist, Fabiano “Ravengard” Veloso passed away on October 22, 2020.

MUDA VK emerged in 2005 from two Vila Kennedy theater groups, Potemgy and Mario Lago, which started organizing plays and shows together about sustainability, environmental education and solid waste management. From 2005 on, they gathered organic residues at the local Sunday open-air market and composted them. At the same time, they collected recyclable materials and electronic waste, transforming them into art. Theater has always been Raven’s passion, and sustainability, his calling.

Earlier this year, two months before his passing, in an interview for Voz das Comunidades, he justified the need for green grassroots favela activism and an urban composting movement: “Over 50% of all organic material ends up in the wrong place, when it should become resources. This is just wrong. We use public funds, our tax money, to gather material that we don’t know how much it’s worth and bury it. It is a wrongful, wasteful culture,” he said.

Raven has left a legacy of green practices, activism, sustainable development, culture, love, and dedication to the environment, urban agriculture and food sovereignty.

Raven is deeply missed by family, friends, his community, and the SFN groups that had the privilege of learning from him. Many are now working to keep his legacy alive through their actions.

He was “a dreamer. His work spoke for him,” said Geiza de Andrade, a Vila Kennedy resident, environmental agent, founder of the project Marias in Action (Marias em Ação), and member of the SFN. She makes clear that Raven’s work and dedication will not be forgotten in this West Zone favela:

“He was a true partner to the Environmental Agents team in Rio’s West Zone, taking us to activities across the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), a craft fair, workshops and showing us new techniques for making vegetable gardens, substrates, using almond leaves and grass that are cut at Avenida Brasil and at schools,” said de Andrade. “Ravengard was enchanted by the environment, and worked hard to change not only the environment but people’s habits. He took his dreams and projects into the university. A dreamer who allowed himself to make his dreams come true.”

To Verônica Gomes Martins da Silva, president of The Kennedy Brothers Community Center (CCIK), in Vila Kennedy, Raven was “unique… A person with immense light.” She met Raven through his involvement in various projects in their community, such as MUDA VK—which later expanded and grew into MUDA RJ, impacting communities beyond Vila Kennedy.

Two friends described Ravengard and his legacy as seeds that, if cultivated, will bloom. “He was a bright person who brought a lot of knowledge, wisdom, and was an example of how we can transform this world for the better. I guess our biggest challenge now is to cultivate the countless seeds he left,” said Antonio Oscar Vieira of UFRJ‘s RIPeR project.

“A seed. Raven symbolizes the role of human interaction and connection, proudly participating in countless projects to support his community,” said Valdirene Militão, from Maré favela’s Ricardo Barriga Project. She describes a captivating personality that allowed Raven to thrive in so many different movements:

“I don’t know how to sum up Raven in one sentence. He was a friend and he always put himself as an educator. He was a seed, and he planted seeds in every person he met. Raven was involved in many projects: he was in the Rio Urban Agriculture Network, he was in MUDA UFRJ, he collaborated with Fiocruz’s Productive Backyards initiative in Colônia Juliano Moreira, he was involved with many Vila Kennedy projects and so on. I had the privilege to be at his side.”

Ravengard developed a technique called “Instant Substrate” that mixes grass, almond tree leaves and Ricinus leaves. As Raven used to say, “everything grows from this mixture.”

Ravengard developed a technique called “Instant Substrate” that mixes grass, almond tree leaves and Ricinus leaves. As Raven used to say, “everything grows from this mixture.”

And it was exactly this that attracted the attention of UFRJ professor Lucia Andrade, who invited him to lecture to her students at the university in 2015. He spoke to the extra-curricular course MUDA UFRJ (on agroecological collective action) about his experience, activism, and the project that solidified his presence in academia.

“As soon as she found out about my lettuce, she invited me to give a lecture in UFRJ’s MUDA project,” said Ravengard in an interview with Voz das Comunidades. “I taught a theoretical lesson about the substrate, and how to grow a seedling. The students asked whether I could lecture there again, and I accepted. When I first got in contact with UFRJ’s MUDA, I felt at home.”

As Irenaldo Honório da Silva, from Pica-Pau favela, in Cordovil, said: “There are people who are born to demonstrate their attitudes and thoughts in favor of everybody, and Raven was one of these people.”

Raven’s friend of 15 years, Carla Felizardo, called him “a nurturer of culture” and said that his devotion to his beliefs and culture was present not only in his work, but also in his personal life. “He was very questioning; he questioned society, he questioned capitalism. He made his own clothes to question society, to say that we don’t need to use famous brands, we don’t have to bet on this capitalism. He was seen as crazy, because when you don’t understand something, you think it is crazy. He had a lot of information with him.” Carla also noted that he was a memorable person, with an incomparable energy:

“His personality was very strong, very present. There was no place he was that we didn’t know that Ravengard was there.”

When asked about Raven’s death, Ailton Lopes, from the Trapicheiros Residents’ Association, in Tijuca, wrote the following statement: “Our condolences to family, friends and students for the loss of a great warrior on environmental issues. Our Trapicheiros community had the privilege of participating in a workshop with this master. On Sunday, September 16, 2018, our community was visited by the Project Manivela team and MUDA VK and the construction of the instant substrate vegetable garden and recycling bins began. It was a total success, we managed to plant our first seeds and open some recycling bins, and we counted on the participation of adult residents and children who had fun.”

Raven died on October 22, the same day that he was due to pose a question to Rio de Janeiro’s mayoral candidates at the Sustainable Favela Network’s Zoom debate. His question was:

“In Rio de Janeiro, the municipality pays R$1.3 billion per year to collect and dispose of solid waste. Given that 54% of this waste is organic, that means we spend over R$600 million to collect and bury organic waste, losing money and prime material for urban gardens, not to mention filling the streets with garbage trucks. On top of that, organic waste stuck in garbage bins attracts insects, rats and puts the public’s health at risk. Organic waste can offer schools a highly-impactful way to engage in environmental education, in gardens, showing the cycle of food production from seed to fertilizer. It is not trash, and maybe we shouldn’t call it waste, since we’re talking about income that we’re missing out on, simply because we don’t incentivize and are incompetent in separating it out. [As candidate for mayor,] what is your proposal for the reuse of organic and inorganic waste in the city of Rio de Janeiro, and how will you transform waste into an opportunity for income generation in [favela] territories, guaranteeing raw material and sources of local employment?”

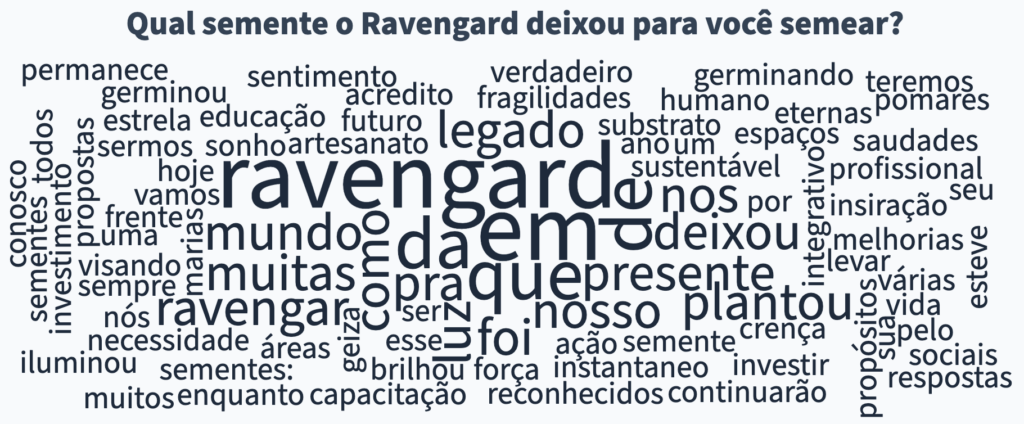

In the words of Militão, Raven “will be sorely missed by all those who had contact with him,” a sentiment that was confirmed by members of the Sustainable Favela Network during its third annual full-network meet-up on November 7. During the event, there was a scheduled activity to honor his memory, a collective moment of remembering his activism as a way of overcoming the feeling of loss. At the end of the session, SFN members were asked “What seed has Ravengard left for you to sow?” and a technological homage in the form of a word cloud was formed. It was a visual representation of Ravengard’s legacy continuing to bloom.

Ravengard has made the world a greener, healthier, and happier place, and his legacy will live on.