The article is part of a partnership with the Center for Critical Studies in Language, Education, and Society (NECLES), at the Fluminense Federal University (UFF), to produce articles to be used as teaching resources in public schools in the city of Niterói, Rio de Janeiro’s sister city across Guanabara Bay.

The virtual world, particularly social media, has reduced distances and created convenience and connections which a little over a decade ago would have been impossible. During the Covid-19 pandemic—with the necessity for social isolation—teleworking and virtual meetings have been essential alternatives to allow us to maintain our lives. Were it not for online events (albeit slightly overdone), we might have died of boredom.

Who knows, perhaps through this virtual life some of life’s injustices can be corrected and even brought to an end. An example is the unjust arrest of young Luiz Justino, a resident of Grota, a neighborhood in Niterói, who was considered a suspect as per usual police standards and ended up in a prison cell. Thanks to an enormous online and in-person mobilization, and to the repercussion in the press, the arbitrary nature of the arrest was reversed and Justino was released. It is important to remember that Justino is a young black man and a cellist in the Grota Orchestra, a fact which helped mobilize the public.

His case, where a photo collected from his social media feeds was included in a Civil Police database, sparked questions of how and why the police keep an album of photos of young black youth to include as suspects. And, more than that, why are these “suspects” overwhelmingly black?

From then on, other cases with the same characteristics—a young black man walking down the streets of Niterói is approached and since his photo is already in the police database, often collected from social media, he is arbitrarily arrested—began to emerge. It is worth bearing in mind that according to a survey conducted by Nexo, Niterói is one of the cities with the largest white population in the country, and one of the most racially segregated in the world. According to Casa Fluminense’s Inequality Map, 88% of victims of police killings in Niterói in 2019 were black.

Following the case of Luiz Justino, there was that of Danilo Félix, 25, who was stopped by plainclothes police and taken to the 76th Civil Police station in Niterói, accused of armed robbery and imprisoned after being recognized by the victim through a photo. The lawyer on the case sustained that the photos used by the police for identification were taken from Félix’s Facebook profile. The young man spent 58 days in prison. On the day of his trial, September 28, a large mobilization of the black and artists’ movements of Niterói took place in front of the Niterói Courthouse. At around 6pm, the news of Félix’s release was announced, causing a general commotion.

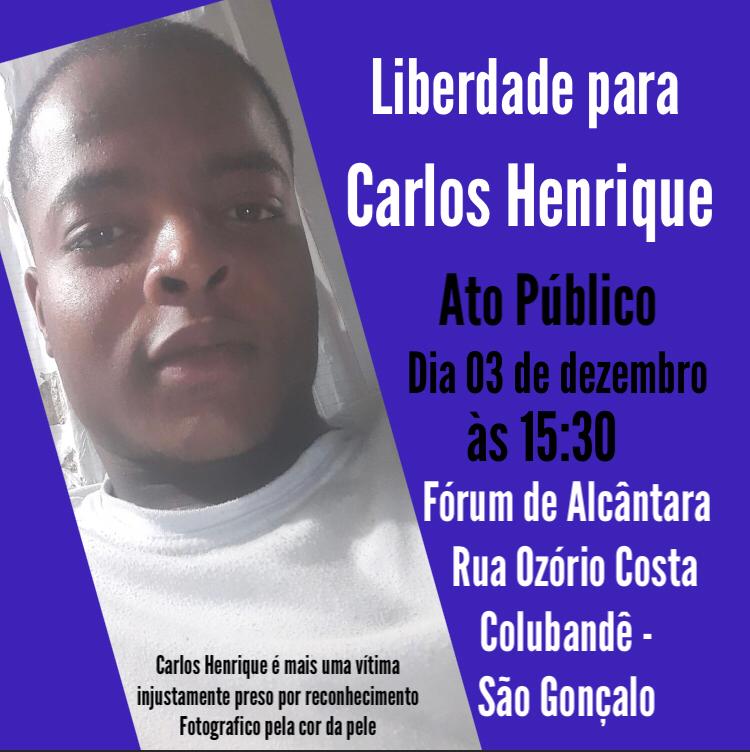

But the cases did not end. A similar one is that of Carlos Henrique de Santana Moreira, a young man arrested while working at a moto-taxi stand in Niterói during a police check that used a photo to identify him as responsible for a 2017 theft. Motivated by the success of the mobilization resulting in Félix’s release, the families of three young men with cases with the same characteristics—Danilo Félix, Carlos Henrique de Santana Moreira and Jefferson Ribeiro—together with the black movement, organized a demonstration on October 15, in front of the Alcântara Courthouse, in Colubandê, a neighborhood of São Gonçalo, on the day of Santana Moreira’s trial. Unfortunately, the presumed victim did not show up, which could have guaranteed the young man’s release. Nevertheless, the judge on the case rescheduled a new trial for December 3. The families and black civil society movements rescheduled the mobilization for the same day.

Soon after, on November 17, another mobilization took place at the Niterói Courthouse due to yet another case of the same nature. This time, it concerned Jefferson Ribeiro, a young man of 21. Ribeiro was on his way to work, on September 1, when he was stopped by members of the Niterói Presente force at around 6pm, in the neighborhood of Charitas. The police officers declared there were three outstanding arrest warrants against him for armed robbery, and Ribeiro was arrested without proof.

The November 17 demonstration—organized by Ribeiro’s mother and sisters, civil society and black movements—began at the same time as the trial, at 3pm. As with Danilo Félix’s trial, the hope was that the sentence would be announced at 6pm. At approximately 3:30pm, however, the lawyer told the family, “He has been released, but the judge has requested that the demonstration be broken up.” With a mixture of joy and outrage, the family thanked supporters for their presence and asked that the demonstration be brought to an end. Shaken, Ribeiro’s mother, Adriana Ribeiro do Nascimento, spoke a little about how this process has been:

“Life gets hard. Something like this shakes up the entire family. Particularly the mother, who doesn’t wish something like this for her children. It’s very difficult, it’s very painful. I’m very thankful for the collaboration and to everyone who has been around giving support, helping out. It’s really important to know that there are people who like us. Being black, it’s difficult to find someone who will hold us, believe in us, support us. I have to thank everyone who is here. We have to continue this mobilization and mothers have to believe their children and fight, not stay quiet! They can’t do it alone, they have to shout. They have to ask for help, like my daughter did.”

Justino’s, Félix’s and Ribeiro’s cases were reversed, very likely as a result of popular mobilization on social media and in person. There are more cases still, mapped out by the Niterói Municipal Council’s Human Rights Commission, including that of Santana Moreira; of the brothers Everton and Jefferson de Azevedo Barcellos; of Laudei Oliveira da Silva; of Nathan Nunes Lopes Batista; of Carlos Eduardo de Oliveira; of Rafael Santos Maciel; and of so many others which have not yet come to light and so many others that have not yet happened, but whose Facebook, Instagram, and other profile pictures are already in the police online album.

To denounce these abuses committed against young black men by the Niterói police, city councillor Renatinho do PSOL, President of the Niterói Municipal Council’s Human Rights Commission, along with a group of representatives from civil society movements, sent the United Nations (UN) a letter denouncing these human rights violations and cases of racism.

In addition to the Niterói Municipal Council’s Human Rights Commission, the letter is signed by Justiça Global, Grupo Tortura Nunca Mais do Rio de Janeiro (Torture Never Again Group), the Instituto de Defensores de Direitos Humanos – DDH (Institute of Defenders of Human Rights), state representative Renata Souza (the president of the Human Rights Commission in the Rio de Janeiro State Legislative Assembly—Alerj), and state representative Flavio Alves Serafini, who is also a member of Alerj’s Human Rights Commission. View the document sent to the UN here.

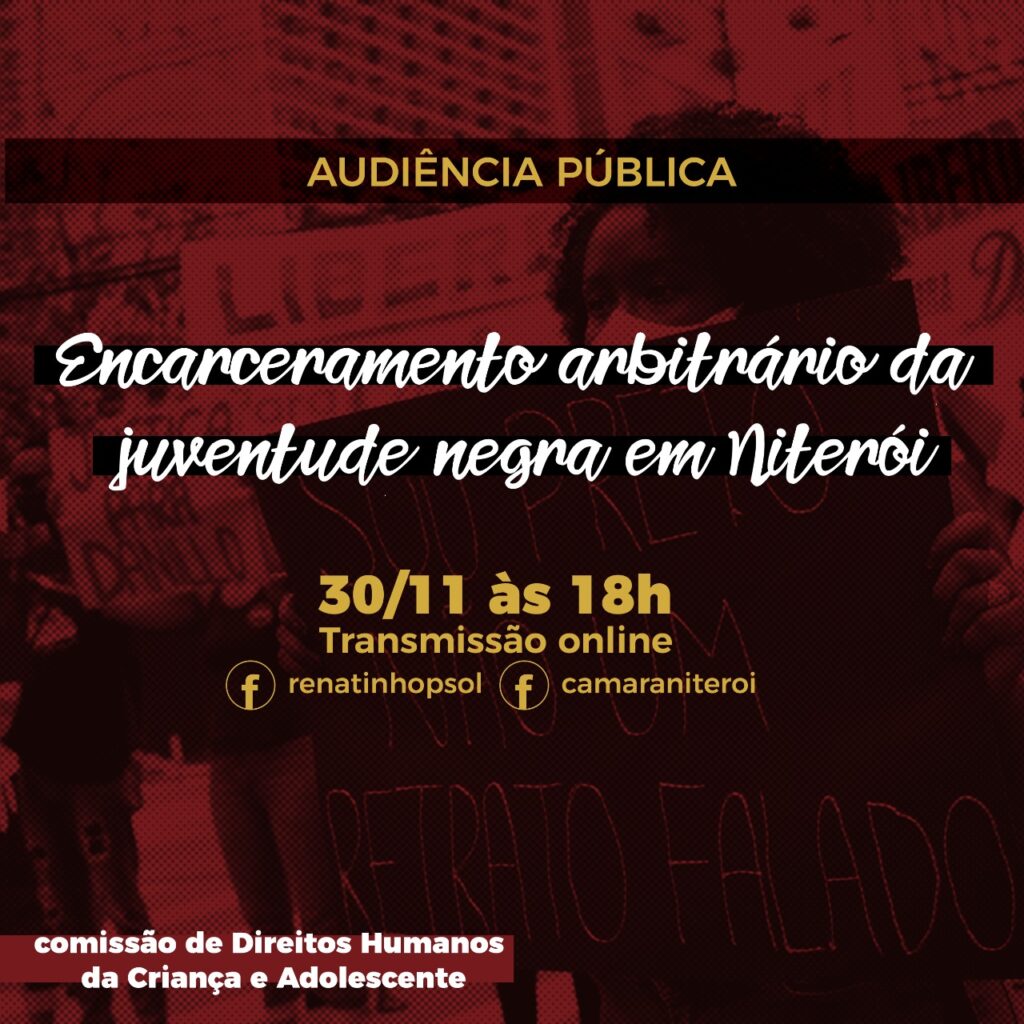

On November 30, 2020, .at 6pm, the Niterói Municipal Council’s Human Rights Commission held a public hearing on the Arbitrary Imprisonment of Black Youth in Niterói. The hearing was broadcast live by TV Câmara, the Council’s television channel.

The Niterói Municipal Council’s Human Rights Commission mapped out nine cases, which took place in recent months in Niterói, of innocent black men who were deprived of their freedom after going through a flawed process of photographic “recognition” in the city’s police stations, through photos taken from their social media and illegally included in police photo albums around the city.

In most of these cases, there is a behavior pattern: young men, all of them black, are stopped in an arbitrary manner by police officers in the streets of the city of Niterói. The hearing was conducted by the president of the Council’s Human Rights Commission, councillor Renatinho do PSOL, who has already denounced this racist state policy to the UN. Family members of the victims of police abuse and representatives from human rights organizations took part in the hearing.

On December 3, at 3:30pm, there was a demonstration for the release of Santana Moreira at the Alcântara Courthouse.

Watch the video of the “Public Hearing, Arbitrary Imprisonment of Black Youth in Niterói” Here:

Alessandro Conceição is a resident of Morro da União, a journalist, and a Master of Ethnic and Racial Studies. A versatile black “artivist” with the Center for the Theater of the Oppressed, his journey with the theater started in 2001 with the play Pirei na Cenna, mental health projects, culture points, and with the formation of popular theater groups, in addition to experiences performing in Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, the United States, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Spain, Mozambique, Zambia, Senegal and Uruguay. In the antiracist fight he is an artist-activist from the group Color of Brazil (Cor do Brasil) and the collective Siyanda Black Experimental Cinema. In the arts of life he has been a street vendor, a trainee at a bank, an attendant in a chocolate shop, and a social educator.