Over 1,000 days have passed since the dark night of March 14, 2018 when Marielle Franco and Anderson Gomes were murdered, but questions about the motive of the crime and identity of the person who ordered it remain unanswered. Ironically, the 1,000 day anniversary was December 8, also National Justice Day in Brazil, a day celebrating the Brazilian judicial system.

With a strong sigh, Anielle Franco, Marielle Franco’s sister, takes a deep breath before she speaks. “1,000 days of us waking up every day hoping for better days, of us trying to understand why Mari… Because we don’t understand… they are 1,000 days that I think we will never understand how they could plan a crime of this scale, and no one discovers anything,” said Anielle, a teacher and currently director of the Marielle Franco Institute.

Elected to Rio de Janeiro City Council with 46,502 votes, sociologist and city councilor Marielle Franco was executed in an ambush in Rio’s downtown Centro. Her driver, Anderson Gomes, was also killed. Two people, Ronnie Lessa and Élcio de Queiroz, are accused of committing the crime, but their trial has not begun. A trial by jury is likely to take place in 2021, but the two men’s lawyers filed an appeal in September 2020.

“1,000 days of us waking up every day hoping for better days.” – Anielle Franco

To mark the 1,000 day anniversary (#1000DiasSemMarielle), the Marielle Franco Institute and Amnesty International displayed 1,000 clocks at the entrance of the Rio de Janeiro City Council. The clocks all went off at 8am, in an “alarm call protest” to demand justice from the authorities.

Ver esta publicação no Instagram

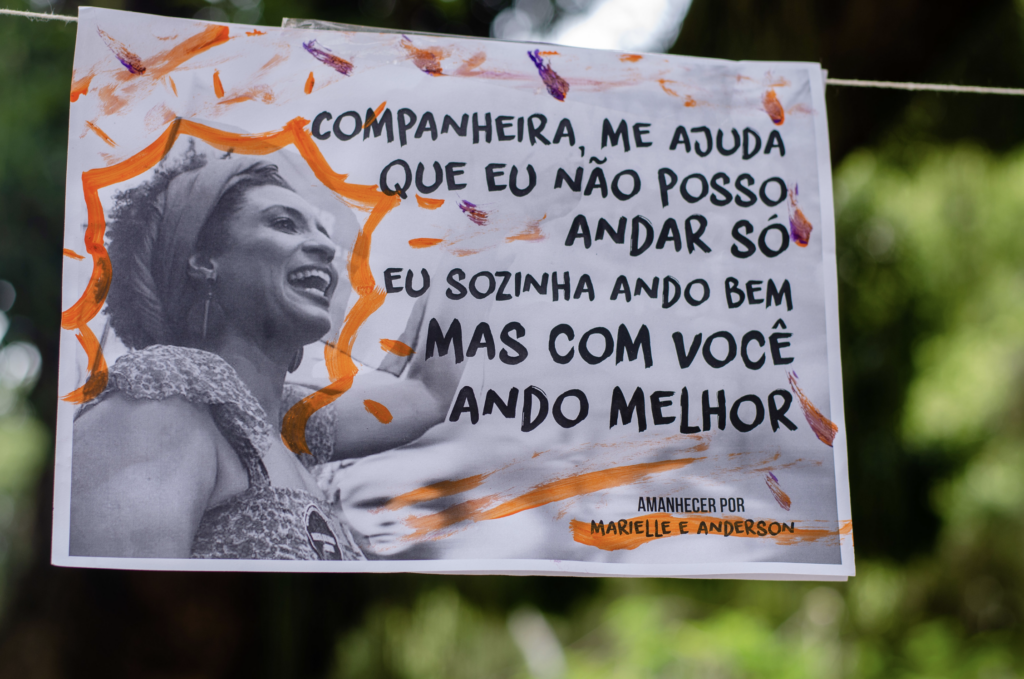

“It’s past time for one of the worst attacks on Brazil’s fragile democracy to be explained,” read the post for the protest action #1000DiasSemRespostas (1,000 Days Without an Answer), which took to the streets—with banners and posters put up in many parts of the city of Rio de Janeiro, as well as in other Brazilian states—and social networks, with posts from politicians, artists, activists, fans and people who voted for the city councilor.

1.000 dias da morte de Marielle Franco e queremos saber, quem mandou o vizinho do Bolsonaro matar Marielle?

Seguimos na luta.#1000DiasSemMarielle #1000DiasSemRespostas

QUEM MANDOU MATAR MARIELLE

Marielle pic.twitter.com/bpb8t73dyt— tody (@JooPaul83353862) December 9, 2020

1,000 days since the death of Marielle Franco and we want to know, who sent Bolsonaro’s neighbor to kill Marielle?

We continue in the struggle.

#1000DaysWithoutMarielle

#1000 Days WithoutResponses

WHO ORDERED MARIELLE’S MURDER

A petition was also created to put pressure on the interim governor of Rio de Janeiro, Cláudio Castro, and state attorney general Eduardo Gussem, for justice.

“It’s very sad to watch my mom, Luyara, and my dad, to see how they look when they talk about Marielle. It’s very sad to reach this 1,000 day mark with my dad in the hospital due to Covid-19. It really upsets me. I really want to have the power to take away some of their pain, you know?” says Anielle Franco, during an interview to RioOnWatch, on the 1000th day without an answer.

Raised in Maré, a black woman, sociologist, intellectual, human rights activist, feminist, and member of the LGBTQIA+ community, Marielle was executed 14 days after being appointed as rapporteur of a municipal commission to monitor the federal security intervention in Rio de Janeiro, and four days after denouncing police violence in the favela of Acari.

“I’m still here, waiting for better days… I’m still hoping that people can understand that Mari was a body that represented multiple struggles, who was not only a left-wing woman like they say, making fun of her and making memes about her,” says Anielle Franco, who is also a columnist for the UOL website.

An English teacher and former volleyball player, Anielle used to help her sister write her speeches. After Marielle’s death, Anielle felt obligated to carry the struggle forward for justice, not just for black people and favela residents, people who her sister fought for, but also to preserve the integrity of her sister’s image.

Since the day after Marielle was killed, the city councilor’s family saw Marielle’s personal and political life become the target of attacks on social media with the publication of fake news and falsely manipulated images, inciting hatred and abuse. Through a kind of “trial by Internet,” Marielle’s life was judged through the publication of false information. The attacks polarized opinions, even about the relevance of investigating the crime, which became known around the world.

In order to fight for justice, defend Marielle’s memory, and multiply her political legacy, creating a dialogue with society, Marielle’s family launched the Marielle Franco Institute. “I hope that in a while, people understand our strength and our desire to create a dialogue, to build things together, mainly in support of black women,” says Anielle.

Her voice breaking, stuttering a little and taking deep breaths, Fernanda Chaves, 45, Marielle Franco’s former parliamentary aide and a journalist, agreed to talk about the lack of State answers as to who ordered Marielle Franco’s murder and why. “No one stood trial yet. There are people who have been accused of the assassination, but they’ve still not been tried. It’s shameful! We still haven’t got any answers,” she says.

Marielle Franco’s communication coordinator, Chaves was in the car at the moment of the assassination, but escaped the ambush. “1,000 days have passed, with no peace… [deep breath] with no ability to return to normality. It’s just not possible! Life goes on, projects continue to exist, things are in a way getting back to their daily rhythm, but there’s no normality. They killed Marielle 1,000 days ago and there are no answers,” Chaves vents.

Chaves speaks of missing Marielle Franco in every dimension, from the personal to the political. “They tore Marielle away from us and, when I speak about what I miss about her, I’m speaking about more than just missing her as a person. I miss her politically too. I miss the space that she took up, with everything that she represented. I miss going with her to the market in the morning, but I also miss thinking with her about ways to make life better, to think politically, to build things…”

Chaves speaks of missing Marielle Franco in every dimension, from the personal to the political. “They tore Marielle away from us and, when I speak about what I miss about her, I’m speaking about more than just missing her as a person. I miss her politically too. I miss the space that she took up, with everything that she represented. I miss going with her to the market in the morning, but I also miss thinking with her about ways to make life better, to think politically, to build things…”

For Fernanda, “the people also miss this… Marielle held in her body all the causes that she defended. I am absolutely sure that she is incredibly missed in the space where she was. There’s a huge empty space there, politically speaking.”

“Marielle held in her body all the causes that she defended.” – Fernanda Chaves

The city councilor fought for a more just society, free from all forms of oppression and exploitation. She was tireless in her defense of human rights, working to support victims of violence and their families. Because of this, she was able to represent the majority of the population in all its diversity: women, black people, favela residents, young people, members of the LGBTQIA+ community, and working-class people.

Chaves met Marielle Franco in 2006 during the human rights campaign against the Military Police’s use of heavily armored vehicles. In 2007, Chaves and Marielle both worked for then state deputy Marcelo Freixo: Chaves was Freixo’s media coordinator and Marielle worked on issues to do with land and human rights. They became friends from that time. Fernanda left this job in 2013 and went to work at the Brazilian Senate.

Three years later, in 2016, Marielle Franco, who had just been elected to her first term with the fifth-highest vote tally in Rio de Janeiro, invited Chaves to work as her media coordinator in the term that would begin in 2017.

“What else can I tell you about December 8—exactly 1,000 days since that dark night when criminals showered our car with bullets? All I can say is that exactly 1,000 days have passed since they killed a friend, confidant, neighbor, boss, and godmother to my daughter.”

A Dawn for Marielle Franco

Sidney Teles, 62, a social educator and human rights activist, worked with Marielle for 10 years. Ever since his friend and colleague was killed, Teles and his son have woken up early together to participate in the “Dawn for Marielle” protest actions. This year was the third year of the event in Praça Seca in Rio’s West Zone, featuring posters, stickers and sunflowers.

“Completing 1,000 days without us finding out who ordered Marielle Franco’s assassination and acknowledging that the genocide of black people in Brazil today reaches children and teenagers directly makes us reflect on the importance of a person like Marielle. We will not be quiet. The living memory of Marielle is always with us. Her killers will always carry the weight of her body,” says Sidney.

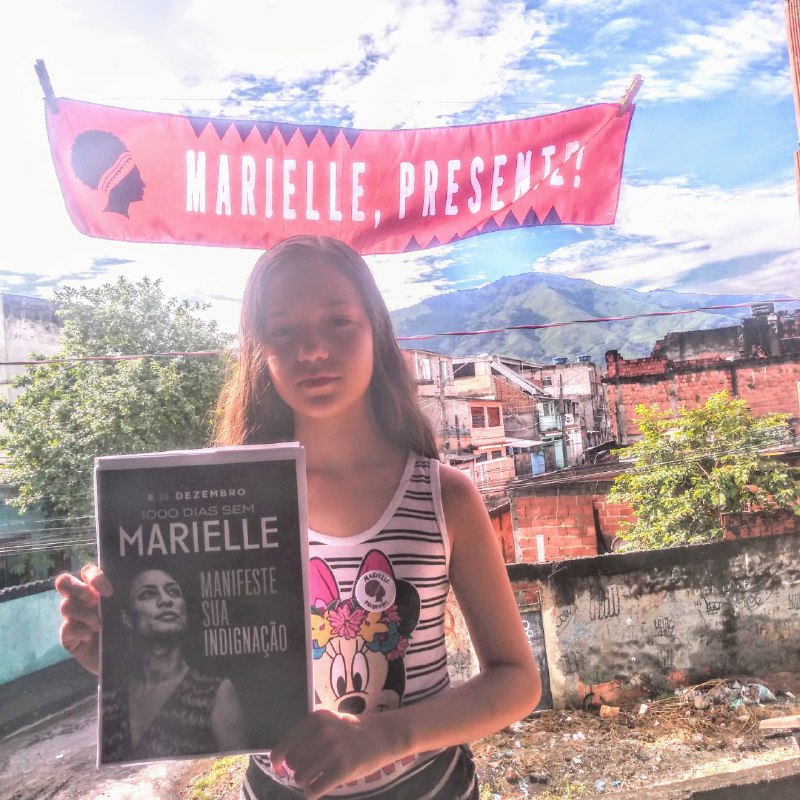

In Vila Aliança, in Rio’s West Zone, salesman Carlos Motta, 40, and his 12-year-old niece, Caterine do Nascimento, a student, also got up early to denounce the 1,000 days without a solution to the crime. They extended a banner decorated with the colors of Marielle Franco’s soccer team, Flamengo, and printed posters to participate in the campaign. Motta met Marielle through community activism in Maré, “before she thought about becoming a politician,” he says. Now Motta is part of a group called Red-Black Democracy (red and black being Flamengo’s team colors).

The Dawn for Marielle event included demonstrations in many cities across the country as soon as the sun came up on December 8, with activists, politicians, artists and fans of Marielle taking to the streets and social media.

In Brasília, activists from the city councilor’s political party, the Socialism and Liberty Party (PSOL), displayed banners on one of the city’s main roads.

At night, a group of activists projected a tribute to the city councilor on to the dome of the National Museum of Brasília.

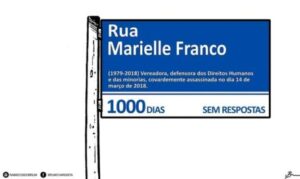

In Santo André, São Paulo, a group of activists also took to the streets on the morning of December 8, carrying posters and an enormous banner with the image of a street sign with the name of the councilor, which has become a symbol of the struggle for justice after it was broken by Daniel Silveira and Rodrigo Amorim, who were, at the time, Rio de Janeiro candidates in the 2016 elections for federal and state legislature, representing the Social Liberal Party (PSL).

Statements about the Significance of the Dawn for Marielle Campaign

Flávia Cândido, 39, a teacher and resident of Maré in Rio’s North Zone, who worked in Marielle’s legislative office until her assassination and who is part of the PSOL party nucleus in Maré, explained to RioOnWatch—emotional, and calling for calm in order to breathe—why events like Dawn for Marielle are important in the struggle for justice and memory:

“When our PSOL nucleus and other nuclei in the party highlight Marielle’s absence [through these actions] we remember a Marielle who was not just a woman from Maré, but a Marielle who chose to be a city councilor, who chose to be a politician and who was torn away from this. We are remembering this strong and brave woman who chose politics as her way of fighting.”

Pâmella Passos, 36, a friend of Marielle’s, described the significance of these 1,000 days and how she’s been deprived of her right to grieve due to having to raise her voice for justice and to fight the attacks on her friend’s memory:

“I would like to be able to be silent, to cope with the devastating pain of losing a friend, but I keep on talking, because justice was still not done. For 1,000 days, we have kept on asking who ordered Marielle Franco’s assassination and we don’t have an official answer. 1,000 days during which disappointments do not stop. Pain does this to people, it can make them lose themselves and end up, in a Machiavellian way, thinking that the ends justify the means. 1,000 days of living with exposure and a lack of care, and to make the sadness worse, not just from enemies. 1,000 days during which I’ve felt like I’ve been living on a chessboard playing a game I don’t want to play, where the enemy pieces scare me and those which I judge to be on my own side can sometimes put us all at risk through their hasty, self-centered actions. 1,000 days during which we’ve lost the great hope for the renewal of left wing politics in Rio de Janeiro. 1,000 days since many of us have lost a good friend. That’s 1,000 days during which we’ve woken up feeling lacerated, but obligating us to be seeds and keep on fighting.”