This is the first article in a five-part series, published in Portuguese by favela-based online magazine Favela em Pauta and titled “Brazils: Stories of the Periphery in the Pandemic.” Each essay comes from a different region of Brazil; this one from the nation’s South. For the original article by Ariel Faria click here. It is also our latest article on Covid-19 and its impacts on favelas.

What stories do the peripheries tell about the pandemic and inequality? This is the question we wanted to answer when we invited five journalists—residents of peripheries in each of Brazil’s five regions—to participate in this project. The idea emerged from the Coronavirus in the Peripheries Map, an initiative of the Marielle Franco Institute which registered more than 540 collectives that act on the frontlines against Covid-19, in favelas and peripheries across the country. Engaging with the data and stories of these collectives and what they have witnessed, the visions of these five journalists show that it is possible to understand the simultaneous similarities and differences of living in the different Brazils that make up Brazil.

‘We Are People and Stories, But We Are Invisible’

Verse 1

Invisible like the virus that crosses continents

Alone on the streets that connect so many.

On the margins of society, on the verge of the crisis.

Facing the reality of such a sad State.

Incredible, for they are still stories and faces.

Of Mários, Marias, and Josés.

That connect everyone.

Politics for people on the street is defending what’s yours from others.

Corona just reveals who are the priority when you talk about a people.

Amid dogs barking and car horns honking: that is how the routine of Edmilson, a 35-year-old car parking attendant from Porto Alegre, the capital of Rio Grande do Sul, can be defined. His two dogs are named after icons and characters that had important roles in his childhood: Xuxa and Kitana—the former a TV host, the latter one of the protagonists in the video game Mortal Kombat. With his two dogs, he shares his daily meal and the small, improvised shelter made of plastic bags in Parque da Redenção (Redemption Park), which he lovingly calls “Alcatraz Island.”

Located in the center of Porto Alegre, Parque da Redenção is a historic site. The name honors the liberation of slaves in the capital city’s third biggest district. The park’s trees, open spaces and children’s play areas create an atmosphere that attracts residents throughout the year.

Edmilson, who has been experiencing homelessness for six years, smiles when asked about the current moment, saying, “the streets show the best and the worst in them: life.” Edmilson, who practices Spiritism, says that the streets were emptied with the pandemic, bringing new residents who share the same context of abandonment. This scenario laid bare the State’s administrative failure to provide the right to dignity, equality, and security, which are afforded to all Brazilian citizens under Article 5 of the Federal Constitution.

This is also the case of Vila Nazaré, an area in the north of Porto Alegre which experienced forced evictions even during the pandemic. People’s homes were removed in order to conclude the expansion of the Salgado Filho Airport with a new runway. As the process continued, families from the community were unable to follow the main public health guideline against the coronavirus: stay home.

The consequences of the lack of preparedness, and the administrative failure of those who should be managing the pandemic, impacted various social indicators, which undoubtedly influenced the routine throughout the country. One of them is unemployment, which was already growing before the coronavirus arrived on Brazilian soil. According to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), Brazil reached a record 13.5 million people out of work in September 2020.

Beyond the numbers and statistics, the study shows faces and stories. People like Zé, 53, native to Florianópolis, in the state of Santa Catarina who, over the course of a few months during the pandemic, lived through a roller coaster of transformations. A “wanderer,” as he defines himself, the artist decided to live on the streets after not being able to pay his rent, as the venues where he used to perform semi-frequently closed their doors. Without a home, but with a backpack, Zé decided to move cities and try a new start in Porto Alegre.

“Coronavirus has taken a lot from many people. Life, dignity, and most importantly, a home. And these politicians show they don’t really care. We are people and stories, but we are invisible. Maybe we are just numbers,” he says.

Despite the feeling of being seen solely as a number, the invisibility of those experiencing homelessness is revealed in the absence of official data and statistics regarding these citizens. Because of the prerequisite of residence in order to participate in its studies, IBGE does not have a national panorama about the vulnerabilities experienced by these people.

The first national study on homelessness was carried out in 2008 in partnership between the Meta Institute and the former Ministry for Social Development and Fight Against Hunger (MDS). The Population Experiencing Homelessness Census identified the precarious situation in 71 cities. It shows, for the first time in the country, profiles and data about these Brazilians. That year, the study counted 31,922 adults experiencing homelessness, of which 82% were men. The census gathered data on race as well as gender: 67% of those surveyed declared themselves black or pardo.

“I work with sanitizing products every day, but I have never smelled them on any bus.”

In recent years, the faces and numbers of Brazilians who live in situations of homelessness have grown dramatically. An estimate carried out in March 2020 by the Institute for Applied Economic Research (IPEA) indicated a 595% increase compared with 2008. The approximate figure shows 221,869 Brazilians surviving in this scenario. In the country’s South, 33,591 people were reported to be experiencing the consequences of this adversity on a daily basis. The arrival of coronavirus and its associated economic and health ramifications increased the homeless population in the capital cities of Brazil’s southern states. In Porto Alegre, for example, there was an approximate 20% increase according to the Social Center for the Street (Centro Social da Rua). State neglect can also be seen in other areas, such as public transportation.

Verse 2

Between packed buses and long workdays,

With no room for tiredness or for bodies

Transmitting worry and anxiety

From one to the other or from stop to stop?

It doesn’t matter.

Bills have to be paid

Even if the price is your health

wearing out.

We go on trying to keep our balance on the ride

In which the virus of “State” abandonment

Hides.

Waiting for a traditional public transit line in the Porto Alegre Metropolitan Region, the Stella Maris bus, is domestic worker Leonice de Santos, 60. She also awaits the experience shared only by those who work in the city’s central and upscale neighborhoods and who live far from their place of work: the daily worry of overcrowding of buses during the coronavirus pandemic.

Between one trip and another, the routines of Leonice and other workers who depend on public transport every day, share the same uncertainty about preventive and precautionary measures on buses. This is because there is not enough room to maintain the level of social distancing recommended by public health officials. According to data made available by the Porto Alegre city government, which maps coronavirus cases by neighborhood, the areas with the highest levels of contamination—between 741 and 1825—are those farthest from the city’s upscale, central areas.

Having worked for over 30 years as a cleaner, Leonice describes the precarious hygiene levels inside public transport vehicles. “I work with cleaning products every day, but I have never smelled them on any bus.”

Hoping to reduce high levels of crowding and people circulating at the beginning of the pandemic, the Porto Alegre city government issued a series of decrees and restrictions regarding the use of public transport and commercial establishments in the city. The number of buses in circulation was reduced by 40%, the number of bus passengers per vehicle was capped, and other measures were taken such as restricting the use of student passes.

Overcrowded urban transport in areas outside the city center is a characteristic that repeats itself in other states of Brazil’s South. According to Francielli Saczuk, who is studying veterinary medicine at the Federal University of Paraná, it is possible to see a difference in the number of passengers from one zone to another. In her view, the number of vehicles offered in wealthier areas is distinctly higher, while others live with precarious services. “I see people complaining on social media, on communication portals, and in other places, saying that since the beginning of the pandemic, buses that are going to the outskirts of the city are crowded and that they decreased the size of the fleet,” she says.

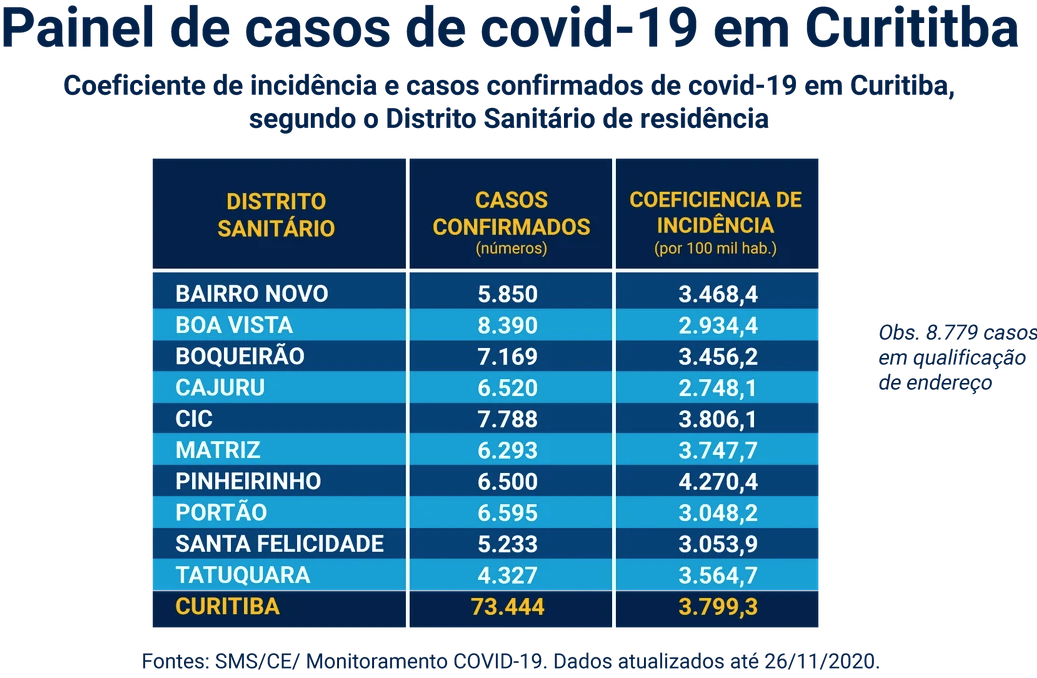

In October 2020, the Paraná State Accounting Court (TCE-PR) identified packed buses circulating in Curitiba. The organization emphasized that social distancing measures are essential to combat coronavirus and that the inadequate transport situation represented a real risk to the health of passengers. The bus authorities in Curitiba denied the accusation. Living with this situation, the areas furthest from Curitiba’s center had a considerable increase in coronavirus infections, according to the Municipal Health Secretariat.

A similar situation was registered in Florianópolis, the capital of Santa Catarina. The city government banned public transit vehicles at the beginning of the pandemic, but on the first day that buses were allowed to circulate again, overcrowding was registered during certain periods of the day, breaking the security and prevention rules that had been decreed (stipulating that buses run at 40% capacity).

“In poor neighborhoods, we’re not scared of the virus, we’re scared of losing cash because of it.”

As well as other indicators, such as race, location is a determining factor when making public resources and mechanisms available to assist the population with prevention and health care, be it physically, psychologically, or financially. This type of management had a particular impact on one specific part of the Brazilian population: the black population.

Verse 3

In the dark, the little black boy disappears

In the light, he is forever sought

In the day candies are sold by black bodies

Riddled by bullets at night

Squeezed in the middle of the alley

We are black bodies trampled over

At the funk ball that causes fear

High society gets down on high heels

Put your hands in the air, today is a day off, hey hey

White dude thought it was a robbery, I told him to stick it, tee-hee-hee!

Despite the fact that the first registered cases of coronavirus in Brazil were linked to people in higher social classes, the real impacts of the virus were felt in the daily lives of those living in Brazilian peripheries. Among the many factors that contributed to the fast spread of the virus in these regions, the main factors were those deeply rooted since these areas were formed: vulnerability and social inequality.

For people living in the peripheries, coronavirus has many consequences, among them destabilizing their physical, mental, and financial health. It is important to note that the vast majority of residents of these areas are considered black or pardo and that they also need to face the reality produced by the pandemic in Brazil, which amplified the lack of employment opportunities.

According to data revealed by the National Household Sample Survey during Covid-19 (PNAD Covid-19), more than 15.3 million people stopped seeking work due to the pandemic or due to lack of jobs at their localities. Among them, 9.7% of those considered black or pardos stopped looking for work, as compared to only 5.9% of whites.*

These statistics show that Brazilian racial inequality continues to increase at full speed, which consequently affects the daily lives of black peripheral residents. This is the case of Geanderson Silva, 24, a native of Vacaria, in Rio Grande do Sul. Working as a street vendor for the last two years, he always saw the constant movement of people on the streets as meaning more possible clients, sales, and opportunities. But, with the arrival of the pandemic, crowds have decreased and so has people’s confidence in buying products from street vendors.

“People avoid buying things from people like us, who work every day and are more in contact with the streets. I think it’s really because they’re scared. In poor neighborhoods, we’re not scared of the virus, we’re scared of losing cash because of it.”

It is possible to identify organizations that carry out essential work during the pandemic on Favela em Pauta’s #MapaCoronaNasPeriferias, a partnership with the Marielle Franco Institute. In the South of Brazil (Rio Grande do Sul, Santa Catarina and Paraná), the majority of organizations registered on the map are located in areas that are far from city centers. The creation and expansion of this project makes it possible to distribute resources to peripheral areas in each state, and, in addition, helps create solidarity networks.

This is the first article in a five-part series titled “Brazils: Stories of the Periphery in the Pandemic.”

*Data updated from original Portuguese article’s publication date.