This article is the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” Follow our Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas series here.

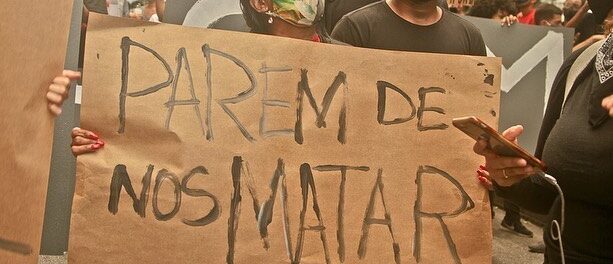

Throughout 2020 racism and anti-racism were widely discussed the world over. The death of George Perry Floyd Jr., 47, lit up a worldwide warning sign regarding crimes that are routinely swept under the rug of whiteness. The American football player was murdered in Minneapolis on May 25, 2020, asphyxiated to death by a white policeman, Derek Chauvin, 44, who knelt on his neck for a long 8 minutes and 46 seconds, with Floyd repeatedly saying to the four policemen present at the crime scene: “I can’t breathe!” The murder caused outrage within the black population and Americans took the streets to protest Floyd’s murder and those of all black people who have lost their lives for the simple fact that they are black—like Breonna Taylor, 26, and Ahmaud Arbery, 25, also murdered by police in early 2020, and also helping lead to the American Uprising of 2020.

Anti-racist protests in the United States mobilized activists from all over the world; people from various countries took the streets in protest under the slogans “Black Lives Matter,” “I can’t breathe,” “Hands up, don’t shoot,” “No justice: no peace! No racist police,” and “Say her name!”—referring to Breonna Taylor, murdered inside her house by police, as well as to other black women victims of police violence. These deaths galvanized the largest wave of protests in U.S. history, and the largest anti-racist protests since the murder of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in the 1960s.

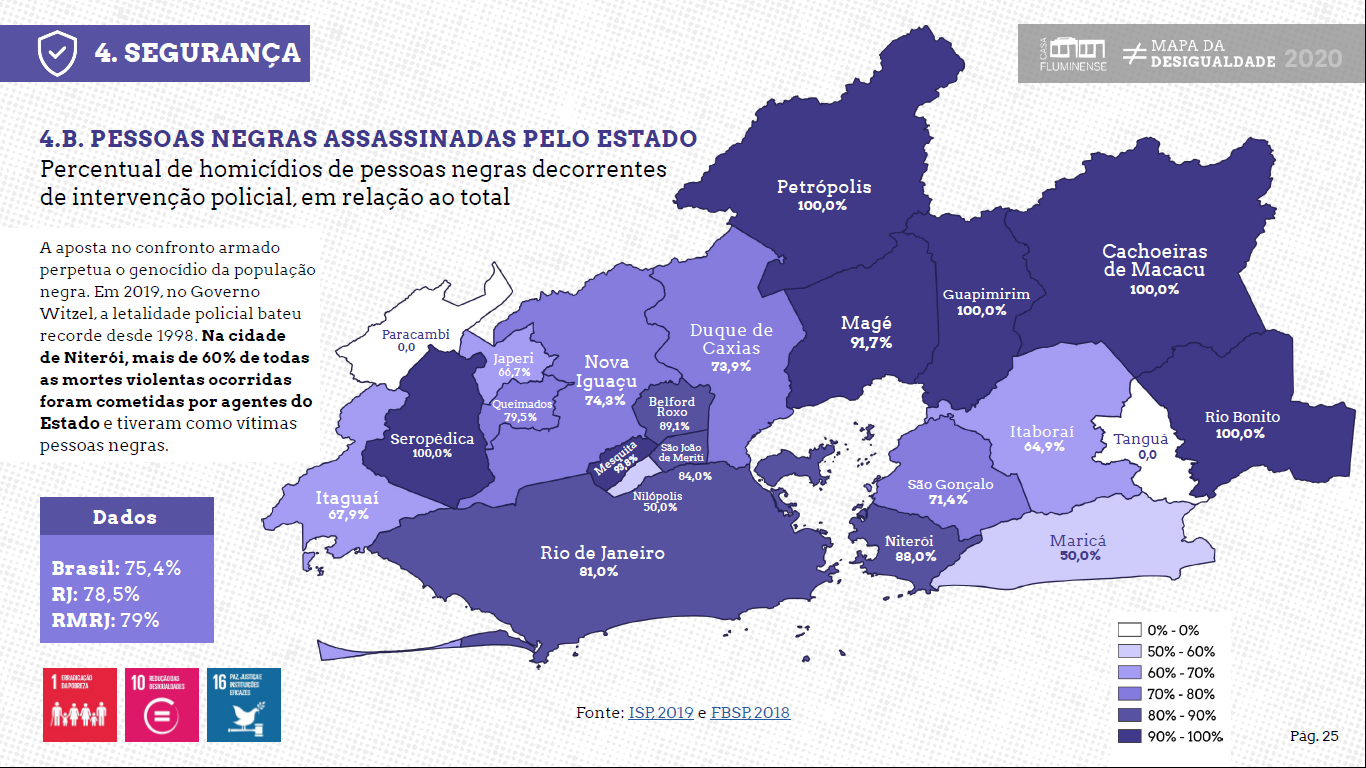

It was no different in Brazil. Many Afro-Brazilians lost their lives at the hands of the state in 2020, causing activists from various cities to rise up against the genocide of black people in a country where a young black man dies every 23 minutes, and where 75.7% of all those murdered are black. This figure is very close to the number of people murdered during police interventions between 2017 and 2018, of whom 75.4% were black. According to the Rio metropolitan region’s research NGO Casa Fluminense‘s Inequality Map, there are five municipalities in the state of Rio de Janeiro where 100% of those killed by police between June 2019 and May 2020 were black. They are: Seropédica, Petrópolis, Guapimirim, Cachoeiras de Macacu, and Rio Bonito. Not to mention that, still regarding the state of Rio, between 2016 and 2019, 91% of children killed by stray bullets were black.

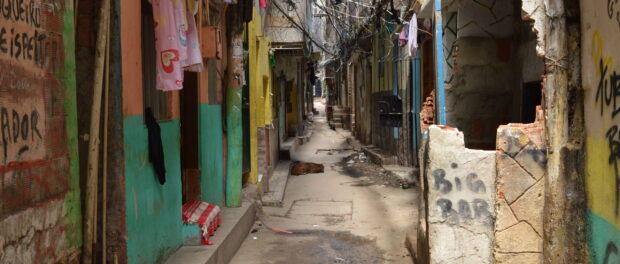

Racism exists and is rooted in society, anchored in speech, behavior, attitudes, systems and narratives that exclude and kill black people. But what about the favela? How does the structure of racial prejudice present itself in the alleys and streets of Rio’s communities?

According to activist and professor of Portuguese Literature and Language, Jonas Di Andrade, 27, “The favela is one of the territories that suffers the most with racism, mainly coming from the state and its repressive apparatus: the Military Police. Through a variety of abuses, plus physical and symbolic violence in view of the large number of black people in these places, we can see how racism operates and takes lives, which doesn’t normally happen in upscale neighborhoods where there are white people.”

Racism from Favela Residents’ Perspectives

Joyce Barbosa, 29, lives in Rio’s largest favela, Rocinha, in the South Zone, and her definition of racism is straightforward: “Racism is those actions, acts, phrases used by privileged people to discriminate against others who are not of the same race, of the same ethnicity as them.” A financial assistant and an undergraduate student in accounting, she believes that racial prejudice is everywhere. “Even with the majority of the population being black, structural racism is rooted [here]. There is racism in the smallest actions and utterances. Even in the favela.” She does believe, however, that there is less racism in the favela than in the asfalto (formal city). “I suppose it’s because there are more black people as residents. But although the favela is less racist, it suffers more racism. Because besides being black, we’re poor, so the prejudices add up; both racial and social, they get mixed up,” she says.

Joyce Barbosa, 29, lives in Rio’s largest favela, Rocinha, in the South Zone, and her definition of racism is straightforward: “Racism is those actions, acts, phrases used by privileged people to discriminate against others who are not of the same race, of the same ethnicity as them.” A financial assistant and an undergraduate student in accounting, she believes that racial prejudice is everywhere. “Even with the majority of the population being black, structural racism is rooted [here]. There is racism in the smallest actions and utterances. Even in the favela.” She does believe, however, that there is less racism in the favela than in the asfalto (formal city). “I suppose it’s because there are more black people as residents. But although the favela is less racist, it suffers more racism. Because besides being black, we’re poor, so the prejudices add up; both racial and social, they get mixed up,” she says.

For Isaías Trajano, 33, also a resident of Rocinha, who identifies as a white man, racism is everywhere and is present in history, but no one identifies themselves as racist. “People don’t come right out and identify themselves as racist. They dodge the issue in all sorts of ways to try to escape current approaches and enforce traditionalist, racist attitudes and customs. But, in short, it’s just bad character. Unfortunately, I’ve had racist attitudes. It’s something still present in my generation. When I was younger, I used to repeat racist jokes, racist phrases, etc. But I’ve been learning, and I’ve evolved on this point. I follow social media and influencers who work with the issue.” The electronics technician says he has seen black friends, also favela residents, suffer with racism. “Since I’m white, I’ve always suffered less prejudice for living in the favela. There has been discrimination after I said where I lived, but until then, I managed to get to places that my black friends didn’t get to. I’ve been stopped by the police several times when I was with black friends and wasn’t searched because I was white,” he says, highlighting racial profiling by Rio’s police.

For Isaías Trajano, 33, also a resident of Rocinha, who identifies as a white man, racism is everywhere and is present in history, but no one identifies themselves as racist. “People don’t come right out and identify themselves as racist. They dodge the issue in all sorts of ways to try to escape current approaches and enforce traditionalist, racist attitudes and customs. But, in short, it’s just bad character. Unfortunately, I’ve had racist attitudes. It’s something still present in my generation. When I was younger, I used to repeat racist jokes, racist phrases, etc. But I’ve been learning, and I’ve evolved on this point. I follow social media and influencers who work with the issue.” The electronics technician says he has seen black friends, also favela residents, suffer with racism. “Since I’m white, I’ve always suffered less prejudice for living in the favela. There has been discrimination after I said where I lived, but until then, I managed to get to places that my black friends didn’t get to. I’ve been stopped by the police several times when I was with black friends and wasn’t searched because I was white,” he says, highlighting racial profiling by Rio’s police.

For Elaine Pacheco, 42, a black woman who lives in Complexo do Alemão, in the North Zone, racism is prejudice based on skin color, social class and religion. In Pacheco’s view, Brazil is one of the most racist countries in the world, and when it comes to favelas, racism happens primarily on the part of the police. “I think racism has a lot to do with ignorance and [lack of] character. I’ve suffered with racism… is there a single black person who’s never been followed around the supermarket or been called a monkey? A while back, I couldn’t really see it, but some nicknames are just plain racist and people think it’s just a way of speaking,” she says. The Complexo do Alemão resident points out that there is a prejudgment that all black people live in favelas. “They think that every black person lives in the periphery. People look at black people with that you ‘live in a favela’ look; that ‘you’re low-income’ look.”

For Elaine Pacheco, 42, a black woman who lives in Complexo do Alemão, in the North Zone, racism is prejudice based on skin color, social class and religion. In Pacheco’s view, Brazil is one of the most racist countries in the world, and when it comes to favelas, racism happens primarily on the part of the police. “I think racism has a lot to do with ignorance and [lack of] character. I’ve suffered with racism… is there a single black person who’s never been followed around the supermarket or been called a monkey? A while back, I couldn’t really see it, but some nicknames are just plain racist and people think it’s just a way of speaking,” she says. The Complexo do Alemão resident points out that there is a prejudgment that all black people live in favelas. “They think that every black person lives in the periphery. People look at black people with that you ‘live in a favela’ look; that ‘you’re low-income’ look.”

Glória Alves, 60, also lives in Complexo do Alemão and says that, as a white woman, she has uttered several racist terms. “I did it without knowing I was being racist, and now some words I just try not to say. Things like ‘you’re on my blacklist,’ that we’ve heard our whole lives and today can see are wrong. But there are still many people addicted to this way of talking, who speak without thinking and are offensive. Nowadays, I stop and think about it; all you have to do is to want to learn, to take these words out of your vocabulary,” she says. Alves confirms that, even living in a favela, she does not suffer from the same prejudices as the black people who live in these communities. “I’ve never been stopped by police anywhere. The only problem is having to give my address for a job. Every day, I hear about people suffering some kind of prejudice, racism for real, on TV, on social media,” she says.

Glória Alves, 60, also lives in Complexo do Alemão and says that, as a white woman, she has uttered several racist terms. “I did it without knowing I was being racist, and now some words I just try not to say. Things like ‘you’re on my blacklist,’ that we’ve heard our whole lives and today can see are wrong. But there are still many people addicted to this way of talking, who speak without thinking and are offensive. Nowadays, I stop and think about it; all you have to do is to want to learn, to take these words out of your vocabulary,” she says. Alves confirms that, even living in a favela, she does not suffer from the same prejudices as the black people who live in these communities. “I’ve never been stopped by police anywhere. The only problem is having to give my address for a job. Every day, I hear about people suffering some kind of prejudice, racism for real, on TV, on social media,” she says.

A barber and resident of the favela City of God, in the West Zone, Jorge Padilha, 43, views racism as the discrimination of another due to skin color. As a black man, he believes there is racism in the favela and elsewhere in the world, but that living in a community escalates prejudice. “People discriminate because they think that, since we live in a favela and are black, we’re thieves, except that, like anywhere else, decent people live in favelas. This kind of person might become a better human being if they don’t let skin color interfere with their lives. Our great Creator made us without any distinction of race or color, so who are we to do that?” he questions.

A barber and resident of the favela City of God, in the West Zone, Jorge Padilha, 43, views racism as the discrimination of another due to skin color. As a black man, he believes there is racism in the favela and elsewhere in the world, but that living in a community escalates prejudice. “People discriminate because they think that, since we live in a favela and are black, we’re thieves, except that, like anywhere else, decent people live in favelas. This kind of person might become a better human being if they don’t let skin color interfere with their lives. Our great Creator made us without any distinction of race or color, so who are we to do that?” he questions.

So What is Racism, and Anti-Racism?

Jonas Di Andrade explains that racial prejudice is more than an attitude, it is a structure. “Racism, as the word itself conveys, concerns the division of people through the criterion of race, of skin color. If we consider our colonial slave past, in which people were torn away from Africa and forced to come here in order to serve, not only as manual labor, but also as a product, we can see how we inherited a set of social, political, legal and institutional practices that have a discriminatory character. People, racialized—non-white, black and indigenous—are victims of this system of power, which is structural (and structuring), individual and institutional,” he explains.

Jonas Di Andrade explains that racial prejudice is more than an attitude, it is a structure. “Racism, as the word itself conveys, concerns the division of people through the criterion of race, of skin color. If we consider our colonial slave past, in which people were torn away from Africa and forced to come here in order to serve, not only as manual labor, but also as a product, we can see how we inherited a set of social, political, legal and institutional practices that have a discriminatory character. People, racialized—non-white, black and indigenous—are victims of this system of power, which is structural (and structuring), individual and institutional,” he explains.

What many people still have doubts about is anti-racism, which are practices of a political, social, institutional, and individual nature that aim to go against the entire power system that divides, dehumanizes, marginalizes, stereotypes and subordinates racialized people (black and indigenous). In Djamila Ribeiro’s Pequeno Manual Antirracista (A Short Anti-Racist Handbook), the author mentions that in order to be anti-racist one must: be informed about racism; see blackness; recognize the privileges of whiteness; perceive internalized racism in oneself; support affirmative action in education; transform the workplace with the inclusion of black employees; read black authors; question consumer culture; understand desires and affections; and, finally, fight racial violence.

Favelas and Racism

Afro-Brazilians who do not live in favelas also suffer from racism. Blacks living in favelas, however, are at the intersection of racial prejudice and social inequality. It is worth pointing out that many people who live in favelas are unaware of the oppression they experience and that, in this context, education plays an important role. “School, which could be a place for raising awareness and for liberation, has been a space not only for the reproduction of racism and other concrete violence, but also for reproducing oppression in the realm of the symbolic. In other words, African and Afro-Brazilian history, as well as the culture and the arts of Afro-descendant populations in the diaspora are not valued,” says Jonas Di Andrade.

Lastly, di Andrade leaves us with a message, “The favela resident, the black favela resident, needs to gain awareness of the various abuses and violence with which their bodies deal every day; they need to fight not only for themselves, but for all others who will be affected by racism. Education plays a fundamental role in this. If we invest in education, placing Africa and no longer Europe at the center, taking an Afrocentric approach, we will be able to move towards building an anti-racist society.”

Podcast in Portuguese available on Spotify, YouTube, and other players.

About the authors:

Gracilene Firmino holds a journalism degree from the State University of Rio de Janeiro (UERJ) with a special emphasis on digital content production. Born and raised in Rocinha, she has been a community communicator for eight years. Currently a journalist for Voz das Comunidades and a reporter for FavelaDaRocinha.com, Gracilene has collaborated with the Agência de Notícias das Favelas and the Rocinha-based newspaper Fala Roça.

Amanda Botelho, 23, native of Rio, was born and raised in a favela. With a journalism degree from Unicarioca, she is a reporter for Voz das Comunidades.

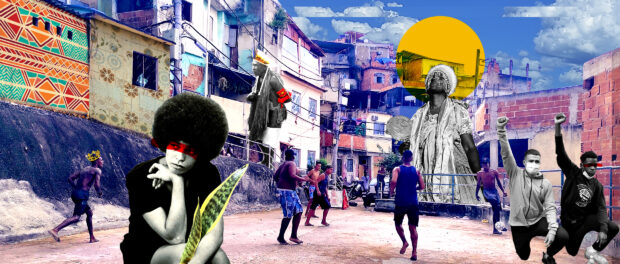

About the artist: Born and raised in Complexo do Alemão, David Amen is co-founder and communication producer of Instituto Raízes em Movimento, a journalist, a graffiti artist, and an illustrator.

This article is the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” Follow our Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas series here.