This article is part of a series on energy justice and efficiency in Rio’s favelas. It is also our latest article about Covid-19 and its impacts on the favelas.

I live in César Maia, a community in Rio de Janeiro’s West Zone. To be more precise, it is located in a district called Vargem Pequena. The community’s official name is Conjunto Bandeirantes I and II, but it’s known as César Maia because the Conjunto (public housing complex) was originally built during Mayor César Maia’s first term, in 1996.

It is a relatively new favela compared to others in the Jacarepaguá region such as Rio das Pedras and City of God, both of which emerged in the 1960s. [It is common for public housing in Rio de Janeiro to grow informally, and thus be eventually recognized as favelas rather than formal housing.] Although it is a “new” community which was built by the State, César Maia experiences a similar problem to many favelas in Rio de Janeiro: blackouts.

They occur randomly throughout the year, but seem to intensify with the arrival of summer; especially at night when people return home after a day’s work and turn on their fans and air conditioners. In short, the power grid has not kept up with the favela’s expansion, and I believe this to be the cause of César Maia’s energy problems.

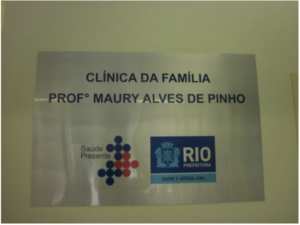

We have a Family Clinic here in the favela—the Professor Maury Alves de Pinho Family Health Clinic—which is constantly being affected by the poor services provided by Light, Rio’s electric utility. The Clinic has three community health teams which tend to the needs of the combined populations of César Maia, Coroado, and Horizonte, all favelas in Vargem Pequena. As you can imagine, this clinic provides an essential service—hard to come by around here—to the population.

As in most Family Clinics, there’s a vaccination room, which is a sad reflection of distributional injustice. About five years ago, they needed to replace the refrigerator that stores vaccines due to constant power cuts which occurred mainly at night. In one of these blackouts, the vaccines had to be transported to another health center so the doses would not go bad. Now the clinic has a cold chamber for vaccines which runs on internal batteries, and can last up to 24 hours without electricity.

As in most Family Clinics, there’s a vaccination room, which is a sad reflection of distributional injustice. About five years ago, they needed to replace the refrigerator that stores vaccines due to constant power cuts which occurred mainly at night. In one of these blackouts, the vaccines had to be transported to another health center so the doses would not go bad. Now the clinic has a cold chamber for vaccines which runs on internal batteries, and can last up to 24 hours without electricity.

It is worth pointing out that the Family Clinics will become Covid-19 vaccination units and, as in previous vaccination rollouts, will be open to everyone, and not just residents of their respective communities.

How many other communities have Family Health Clinics and also experience constant blackouts? Have they all managed to replace their refrigerators, a necessary action given the terrible energy service provided to them? Will favelas, amid this energy neglect, be able to store Covid-19 vaccines? What will be the impact of both energy inequality and distributional injustice on the inoculation of Rio’s favela populations?

As favelas do Rio e a vacina da covid-19. As Clínicas da Família e Centros Municipais de Saúde serão pontos de vacinação. Nem todas as unidades tem geradores de energia. A falta de luz na favela é diária e as vacinas precisam de refrigeração, se não, vão ser perdidas. Ai ai

— Michel Silva (@eumichelsilva) January 12, 2021

Rio’s favelas and Covid-19. Family Clinics and Municipal Health Centers will soon become vaccination centers. Not all of them have power generators. Having no electricity happens on a daily basis and the vaccines need to be refrigerated, if not they’ll be wasted. Oh boy — Michel Silva

It is worth thinking about all of this right now, since it is crucial for the success of vaccination programs in favelas that we understand the true capabilities of each territory’s health units. Since the beginning of the pandemic, there have been no efforts in César Maia to put an end to blackouts; they continue to occur frequently, both day and night. Ironically, there was a power cut while this story was being written.

Another problem is that during the summer, heavy rains also worsen electricity issues. Those who live in a favela or in some neighborhoods on the outskirts of the city will already start to worry when the rain comes, because it is almost certain that lights will begin to flicker. The inconsistent amount of electricity that reaches homes means that household appliances will often have a substandard performance: lightbulbs, for example, will flicker.

At times, energy shortages are a problem only we face. I can say this with certainty, as several times I have happened to be coming home from work at night and notice that everywhere along my journey seems to be lit up, only to get to the community and see that all the lights are out. Why must a favela be an unlit island surrounded by light everywhere? We do not have the same access to services as the neighborhoods around us. Inequality exists here for all to see, in the distribution of electricity and its maintenance; in the allocation and expansion of resources.

César Maia is about 5km from Recreio dos Bandeirantes, a wealthy neighbor of ours, full of luxury apartment blocks. It is not uncommon for us to be without electricity in the favela, while the apartments in Recreio have their lights on. And even when there is a big blackout affecting our community and our neighbor, you see that electricity is always restored first in the upscale neighborhood and then in our community. We need the power grid to be equally maintained! Historically, favelas have been denied the right to safe and legal access to electricity.

“It’s frustrating to come home after a long day at work and not be able to turn on your fan to cool down. Power cuts here have been getting worse and more intense, and even with some improvement, our energy services are still far from ideal,” explains João,* a resident of César Maia.

“It’s frustrating to come home after a long day at work and not be able to turn on your fan to cool down. Power cuts here have been getting worse and more intense, and even with some improvement, our energy services are still far from ideal,” explains João,* a resident of César Maia.

“I moved to the community about ten years ago and I suffer from asthma. As soon as the rain started at night, I’d be scared about not being able to use my nebulizer. I was only able to relax once I managed to buy a device that didn’t rely on electricity to function. Strong winds also cause electrical surges, and we live in one of the windiest parts of Rio de Janeiro,” says Felipe,* another resident of the favela.

Blackouts also lead to several other problems: one of them is the burning or malfunction of household appliances and electronics, not only inside homes but also affecting public infrastructure and service providers. There used to be a time when even the slightest spike in electricity, just a few seconds, would leave us in doubt about whether the Internet would come back or not. In other words, a precarious supply of electricity can cause other public services such as water, telephone systems and the Internet to be precarious too. How can water be pumped without electricity?

A large company that provides telephone and Internet services in the community keeps Internet “distribution boards” installed here. If we were left with no Internet after a blackout, we immediately knew the reason: part of the “board” had burned. Straight away, I would contact the company’s call center informing them of the issue. The operator would respond with, “we’re going to send a team to your residence to check out the problem.” To which I would reply, “Tell the team to check the distribution board because that’s where the issue is. That’s how it works around here: no electricity, a part in the board burns!” During one of the blackouts, there was no spare for the burned part in all of Rio, and the company had to bring a new one from São Paulo. We had no Internet for weeks due to a simple outage that lasted seconds. This problem of not having Internet every time we have a blackout no longer happens, at least not in my part of the favela. But they took years to solve it. The community is divided between Bandeirantes I and II and, sometimes, electrical surges occur on one side but not on the other.

It is clear that community health centers in favelas and in the peripheries—which are often deprived of electricity, water, Internet and phone signals—are unable to care for the population in the way that they should. But favelas also pay electricity fees and taxes—a lot of them! We are entitled to a stable electrical supply, but we seem to have been forgotten. What remains for us is to wait and see how all of these factors will interfere with vaccination programs in favelas.

*The names of the interviewees in the text are fictional in order to protect the identity of favela residents. Joaquim da Silva is also a pseudonym, chosen to safeguard the author’s identity.

Art by: Marcelo Vitor

This article is part of a series about energy justice and efficiency in Rio’s favelas.