This is our latest article on Covid-19 and its impacts on the favelas. It is also part of RioOnWatch’s #VoicesFromSocialMedia series, which compiles perspectives posted on social media by favela residents and activists about events and societal themes that arise. Article originally published December 4, 2020.

The soap opera of Rio de Janeiro’s water shortages now seen in reruns in favela taps.

Amid the coronavirus pandemic, in the state with the highest mortality rate in Brazil, nearing a collapse in its health system, and a thermal sensation of 40 degrees Celsius, residents of Rio de Janeiro faced water rationing in more than 30 of the city’s neighborhoods in December 2020, plus the Baixada Fluminense, according to a survey done by Extra newspaper. In the favelas of Complexo do Alemão, Acari, Complexo da Maré, Tabajaras, Tuiuti, Quitungo and Santa Marta, taps had run dry since November 14, according to residents’ reports on social media.

na favela de voces tbm ta sem agua ?

porque boa parte aqui da maré (se não toda) esta sem agua— DRICA (@adrianumendes) November 17, 2020

is your favela out of water too?

’cause a large part (if not all) of maré has no water

Alô, @CedaeRJ. Tudo bem? Já imaginou o Jardim Pernambuco sem água por quatro dias?

O que tá acontecendo na Maré? Alguma explicação?

Acho que o @MP_RJ também poderia nos ajudar. 🤔 https://t.co/usSpyOpuqD

— Rafael Nascimento de Souza (@nasrafael) November 18, 2020

Original tweet by Rafael Nascimento de Souza: Hello there, @CedaeRJ. How’s it going? Can you imagine Jardim Pernambuco (an enclave of mansions in the upper-class neighborhood of Leblon) with no water for four days?

What’s going on in Maré? Any explanation?

I think the @MP_RJ (Rio de Janeiro Public Prosecutor’s Office) might me able to help us out. 🤔Gizele Martins’s tweet: 4th day without water in the part of MARÉ where I live. One more day…

@CedaeRJ @ladygross @RedeGlobo Então CeDaE de Queimados, está faltando água na Rua Pedro Lima, São Roque, a dez dias!!

Precisamos de vcs !#rjtv #cedaerj #TVRecord #queimadosrj #MPRJ #sbtjornalismo

— Prof. Wallace מורה (@wachasilva) November 30, 2020

@CedaeRJ @ladygross @RedeGlobo So, Queimados CeDaE, there’s been no water on Rua Pedro Lima in São Roque for ten days!!

We need you!

#rjtv #cedaerj #TVRecord #queimadosrj #MPRJ #sbtjornalismo

In response to the complaints, water utility CEDAE said that the shortage in water supply in certain areas of the city was caused by “emergency maintenance on one of the engines of the Lameirão Elevatory Station that serves the municipalities of Rio de Janeiro and Nilópolis,” and guaranteed that, “we are working to conclude its servicing as soon as possible.”

The forecast for the repair was 48 hours, but after more than 15 days, the problem persisted. The “as soon as possible” predicted by CEDAE was suddenly December 20, when the call for tender sealing the sale of the company, expected for the 18, would already be published.

Mais um dia e nada de água nas torneiras… Lembrando que estamos numa pandemia e onde a água é essencial.#CEDAE#VERGONHA pic.twitter.com/ctDwDfxPci

— Jacqueline Ceraso (@jacque_ceraso) December 2, 2020

One more day and no water coming out of our taps… Just a reminder: we are in the middle of a pandemic, where water is essential. #CEDAE #SHAMEONYOU

#cadêaáguanafavela

Inúmeras favelas do RJ estão sofrendo com a falta d’água. Algumas estão sem água há 20 dias. O mais cruel é passar por isso na pandemia. A água pode até salvar as nossas vidas. Governador, Cedae, queremos a nossa água!#cedae #privatizaçãonão #afavelaquerviver pic.twitter.com/qSpts1arxG— Gizele Martins (@giz_omartins) December 2, 2020

#wheresthewaterinthefavelas

Various favelas in Rio are suffering from lack of water. Some have had no water for 20 days. The cruelest part is going through this during the pandemic. Water can even save our lives. Governor, Cedae, we want our water! #cedae #notoprivatization #thefavelawantstolive

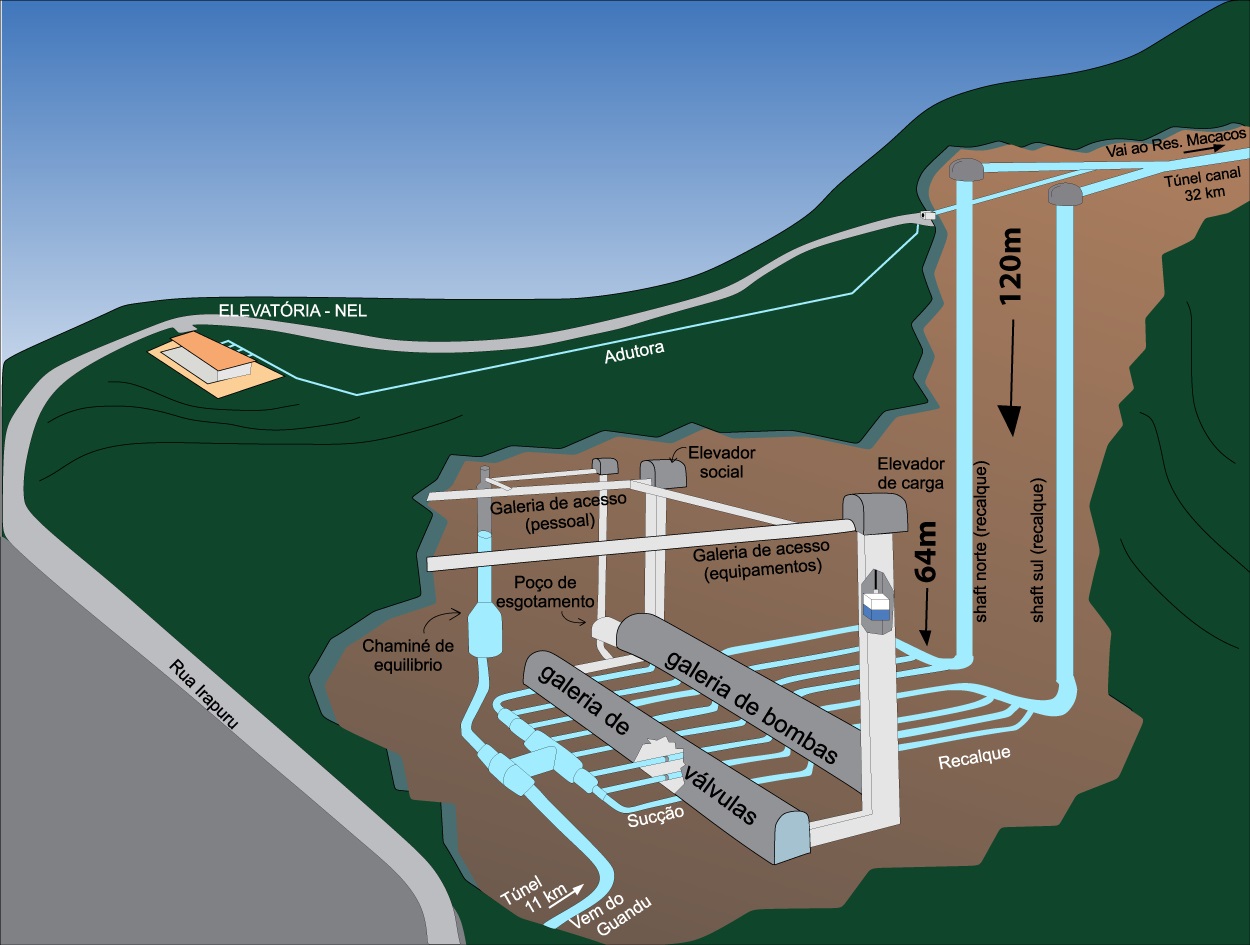

The Lameirão Elevatory Station started operating at 75% capacity due to a fault in three of its pumps. The station, located in Senador Vasconcelos, in Rio de Janeiro’s West Zone, receives approximately half of the water treated at the Guandu Station. In the municipality of Rio alone, it is estimated that more than 1.4 million inhabitants were affected by the shortage, according to data from the Pereira Passos Institute. In some places, when the water arrives, it comes out dirty and has a strong smell.

A @CedaeRJ nunca se preocupou com os territórios de favela, nunca é na segunda onde de Covid 19 não seria diferente. Não seria mesmo. Estamos a quase 1 mês sem uma gota de água, um calor extremo. #Cadeaagua #Covid19nasFavelas

— Nega Rê 🏴 (@RenataTrajano1) December 2, 2020

@CedaeRJ never cared about favela territories, so it wouldn’t be any different during the second wave of Covid-19. Of course it wouldn’t. We haven’t had a drop of water for almost a month, even dealing with extreme heat. #Wheresthewater #Covid19inthefavelas

The Rio de Janeiro State Public Prosecutor’s Office (MPRJ), the Rio de Janeiro State Public Defender’s Office (DP-RJ) and professors from Brazil’s national health foundation, the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz) and the Fluminense Federal University (UFF) held an emergency meeting with CEDAE directors to seek efficient solutions for the supply crisis on November 26.

The company only created a crisis management department for taking emergency measures after this meeting. Among these measures was preparing a diagnosis to identify deforested areas and putting together a supply maneuver plan, which in practice created the “water rotation” or the #mapadaágua.

Rio na pandemia e ocupação de leitos chegando ao limite: RODÍZIO DE ÁGUA. Isso mesmo: Rodízio de abastecimento de água. https://t.co/bn2RWOESkB

— Cecília Olliveira (@Cecillia) December 2, 2020

Original tweet by Cecília Olliveira: Rio in the pandemic and bed occupancy rates at their limit: WATER RATIONING. You got it: A rationing of our water supply.

O Globo newspaper tweet: Residents from regions excluded from Cedae’s rationing complain about water shortage oglobo.globo.com/rio/moradores-…

#Mapadaágua #Cedae

Acesse https://t.co/5w4ysZ29fo e veja se a sua região pode ser afetada pela redução do abastecimento de água nesta quarta, 02 de dezembro. As áreas demarcadas têm a maior chance de terem pontos de desabastecimento, principalmente imóveis em locais mais altos.— Cedae (@CedaeRJ) December 2, 2020

#Watermap #Cedae

Visit cedae.com.br/savewater to see if your region might be affected by a reduction in water supply this Wednesday, December 2. The areas outlined have a bigger chance of suffering shortages, especially properties located on higher ground.

The water rationing “water rotation” map can be accessed through the link or by clicking on the pop-up available on the site’s main page. CEDAE is carrying out emergency repairs to the Lameirão Elevatory Station, which distributes half of the water treated daily in the Guandu plant. The company made a video explaining the problem of lack of supply.

Meanwhile, the average price of a water truck varies from R$450 (10,000 liters at US$80) to R$650 (20,000 liters at US$115) at companies in the North Zone, Benfica and Pavuna, and in Nova Iguaçu, with deliveries scheduled in 48 hours, according to telephone calls made to three water truck sales companies. However, the price can be as high as R$1,000 (US$176).

For assistance with water shortages and requests for a water truck, CEDAE consumers can call the company’s Consumer Service Helpline at 0800-282-1195. To request supply via water truck, the following is required: an active record (being registered and in good standing with the company); informing the capacity of the tank needed; and waiting five days to be supplied by the truck, as outlined by the CEDAE helpline at 5:57pm on December 3.

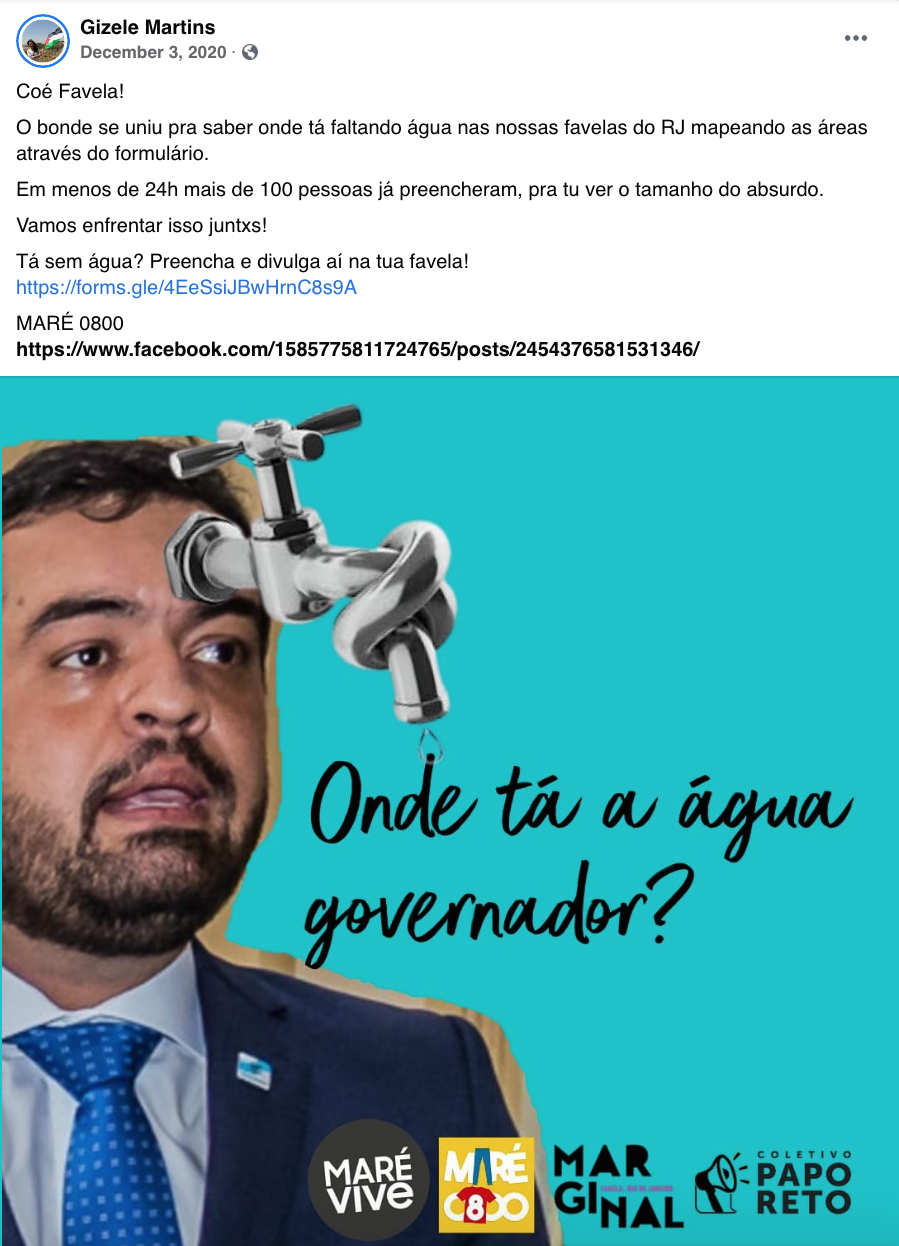

Meanwhile, the collectives Maré Lives, Maré 0800, Marginal Theater Company and Straight Talk, from the Maré, Cidade de Deus and Alemão favelas, have joined forces to map out the water shortage in the favelas and neighborhoods of Rio de Janeiro, with popular participation by filling out a form.

Whassup, Favela!

The crew got together to find out which of our favelas in RJ have no water by mapping out the areas through the…

Published by Gizele Martins on Thursday, December 3, 2020

I Know What You Did Last Summer

It could just be a movie title from the 1990s, but when it comes to the water supply in Rio de Janeiro, this is not a problem of years long gone. The state is going through the second water crisis in a year. In January 2020, residents of Rio de Janeiro sought out social media to report that the water distributed by CEDAE was coming out of taps and filters cloudy and smelling and tasting like dirt.

The cause would be an organic substance called geosmin, produced when there is a lot of algae and bacteria in the water, which has not been proven to be harmful to our health. CEDAE is the state-owned utility responsible for treatment and distribution of water in the metropolitan region.

On January 15, a Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) report pointed out that “it is possible to affirm that the Rio de Janeiro Metropolitan Region is hostage to the quantitative water supply of the Paraíba do Sul River, and to the environmental and sanitary quality of this basin. In spite of the importance of water pollution control in the Paraíba do Sul River basin, the current crisis faced by the Metropolitan Region is due to the insufficiency of the sewage system of its urban areas.”

In June, however, analyses carried out by researcher Fabiano Thompson, professor of the Laboratory of Genetics and Bacteria of UFRJ’s Institute of Biology, in the Oswaldo Cruz Institute Study Center (IOC), revealed that the substance found in the water has a similar structure, but is not geosmin. The research found a strong presence of domestic sewage and of industrial pollution.

Since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, residents of Rio’s favelas have suffered from inconsistent access to tap water. Between March 18 and 23, 2020, the State Public Defender’s Office received 475 complaints of inadequate water supply in 140 different neighborhoods in 14 municipalities of Rio de Janeiro. The vast majority of these reports came from favelas in Rio’s Metropolitan Region.

As of December 4, 2020 (original publication date of this article), the state capital has seen an increase in the number of cases and deaths from the coronavirus pandemic in the past two weeks. According to the State Health Secretariat (SES) bulletin, there have been 3,788 new cases of the disease, with 124 deaths in the last 24 hours. In all, the state of Rio de Janeiro registers 365,185 cases and 22,891 deaths.

RJ: Falta de água já afeta cerca de 1 milhão de

consumidores no Rio e na Baixada FluminenseEm vídeo enviado à redação de moradora da Barreira do Vasco denuncia falta d’água: pic.twitter.com/7gDmnuTm3C

— A Nova Democracia (@jornaland) December 2, 2020

RJ: The water shortage has already affected approximately one million consumers in Rio and in the Baixada Fluminense

In a video sent to the newsroom a resident from Barreira do Vasco exposes the water shortage.

Fiocruz also revealed on December 3, 2020 that the state of Rio de Janeiro has the highest coronavirus mortality rate in the country. According to the survey, there are 131 deaths for each group of 100,000 inhabitants. The institution had already alerted the authorities and the population that the city was close to a collapse in its health system, and could face a serious scenario of lack of access to health services because of Covid-19. Access to water for personal hygiene for regular hand washing is essential for coronavirus prevention.

Já conhece os serviços do nosso site? Com poucos cliques, você pode emitir a segunda via da sua conta, solicitar a inclusão de tarifa social e denunciar ligações clandestinas ou vazamentos de água, entre outros. Acesse https://t.co/3hSvKFgXM5 e confira. #site #serviços pic.twitter.com/IZk40vvbnO

— Cedae (@CedaeRJ) November 23, 2020

Original tweet by Cedae: Do you know the services offered by our site? With a few clicks you can get a copy of your bill, request the social rate and denounce clandestine connections or water leaks, among other services. Access https://t.co/3hSvKFgXM5 and check out #site #serviços pic.twitter.com/IZk40vvbnO

Second tweet by Catherine Perth: WE’RE IN THE MIDDLE OF A SANITARY PANDEMIC AND THOUSANDS OF PEOPLE IN VARIOUS NEIGHBORHOODS HAVE HAD NO WATER SINCE NOVEMBER 19! RIO DE JANEIRO HAS NO WATER!!!

#whereisthewatercedae?

Support RioOnWatch’s tireless, critical and cutting-edge hyperlocal journalism, online community organizing meetings, and direct support to favelas by clicking here.