This is our latest article about Covid-19 and its impacts on the favelas.

A year into the Covid-19 pandemic, Brazil remains in economic and political crisis with no national vaccination plan, underreporting of cases, and unavailable ICU beds, along with record cases and deaths.

On March 17, 2020, the São Paulo State Health Secretariat informed the press that the night before, a 62-year-old diabetic and hypertense man, Manoel Freitas Pereira Filho, in treatment at Hospital Sancta Maggiore Paraíso, passed away due to Covid-19. It was the announcement of the first official death by coronavirus registered in Brazil.

Four months after the start of the pandemic, in late June of last year, the information was corrected by the Health Ministry. Lab exams revealed that the first death by Covid-19 occurred in São Paulo four days prior to that, on March 12, 2020, with the death of a 57-year-old São Paulo resident named Rosana Urbano, at Doutor Cármino Caricchio Municipal Hospital.

The underreporting of cases and deaths from the disease in the country and the chaotic public policies and protocols for controlling and responding to the pandemic—everywhere from health care to social and economic assistance by the federal, state, and municipal governments—were already indicating what the “future” of the pandemic would look like in Brazil. After a year, the country has exceeded 12 million cases and 300,000 officially recorded deaths. Only those who have buried their dead know their names and faces.

Data gathered by a consortium of media outlets, on March 18, 2021, showed that on this day Brazil recorded 2,659 deaths by Covid-19—the third highest number recorded since the start of the pandemic—and that 20 consecutive days had passed with record-breaking average deaths, which now reached 2,096. Bodies are accumulating at cemeteries and hospitals and, according to national health foundation Fiocruz, the situation will deteriorate further.

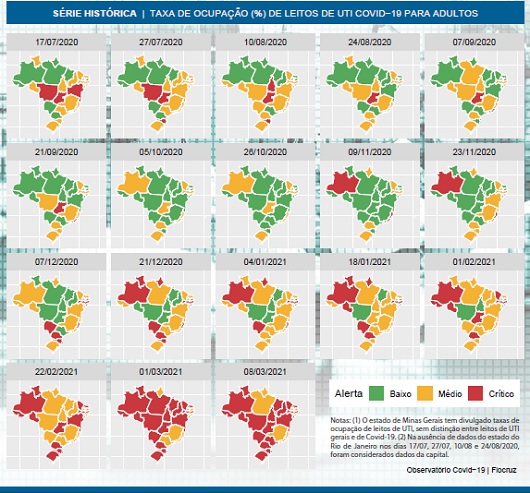

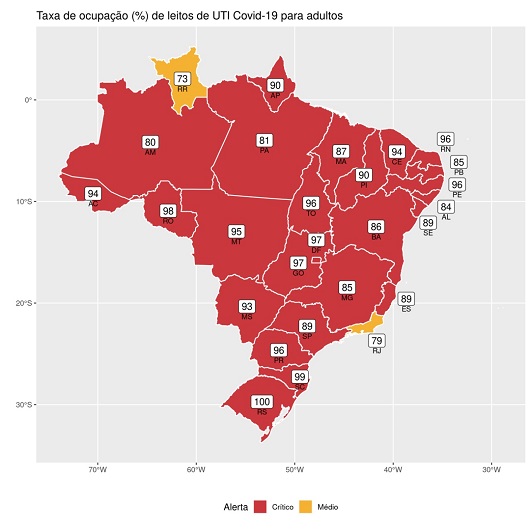

In its Covid-19 Observatory Special Report, Fiocruz stated that the country is experiencing the largest health care and hospital collapse in history. According to the researchers, of the 27 federal units, 24 states and the Federal District have over 80% occupancy rates for Covid-19 ICU beds, 15 of which have rates equal to or exceeding 90%.

In terms of Brazil’s capital cities, 25 of 27 have rates exceeding 80%, with 19 of them exceeding 90%. The latest data collected were included in the Historic Series on Covid-19 ICU Bed Occupancy Rate (%) for Adults, presented by the research center. Based on these findings, Fiocruz called for stricter restrictive measures for non-essential activities.

In terms of Brazil’s capital cities, 25 of 27 have rates exceeding 80%, with 19 of them exceeding 90%. The latest data collected were included in the Historic Series on Covid-19 ICU Bed Occupancy Rate (%) for Adults, presented by the research center. Based on these findings, Fiocruz called for stricter restrictive measures for non-essential activities.

Brazil is currently the country with the highest number of Covid-19 deaths in the world, with 3,438 on March 27, 2021, according to Oxford University. That is 4.6 times the country in second place (USA). This number is higher than the entire European Union (1,980) or the North American continent (1,389). It is 83% of the total deaths in all of South America (4,140). In other words, the spread of Covid-19 in Brazil is completely out of control.

To further complicate the Brazilian situation, within a scenario that already denotes extreme vulnerability, the portion of the population that is poor, residents of favelas and the peripheries—who are black for the most part—are also succumbing to hunger. In an Oxfam report published in July 2020, the organization warned that 12,000 people worldwide could die of hunger daily until the end of the year and that Brazil would be one of the global epicenters of this hunger.

The prediction was accurate. “It’s very sad. People here are eating food from the garbage. We need food and vaccines. What people most need here [in a favela in Rio de Janeiro] is food. They thought Covid was over, so they’re not distributing basic food baskets. The hospitals are totally full. This [new] strain doesn’t take long; in two days it’s all over. They ask people to stay home, to try harder not to go out too much, but how is this possible when people are hungry? Here we had three aunts pass away. My grandson had Covid. My daughter had Covid. We have to join forces to demand a response from this wretched [President Jair Bolsonaro], who is killing people. Today it was my family, tomorrow it could be anyone’s,” reports a resident from a favela in the North Zone of Rio, during a regular meeting of the Covid-19 in Favelas Unified Dashboard.

The Dashboard is comprised of over 20 collectives, institutions, and community organizations that, in the absence of data on the pandemic in Rio’s favelas, united through NGO Catalytic Communities (CatComm)* with the goal of producing data to save lives. According to the mapping—realized by favela leaders, communicators, and residents, in addition to official data collected through a system of estimates based on areas of influence by postal codes—by March 27, 34,173 cases and 3,606 deaths had been recorded in 230 favelas, 224 of which are in the capital city of Rio de Janeiro and six in Greater Rio’s Baixada Fluminense. The number of deaths in Rio’s favelas is higher than in 162 countries.

According to an article by newspaper Nexo, Brazil went backwards 15 years in the last five, with over 84 million people facing some degree of food insecurity. This number has increased day after day with the end of emergency aid in December 2020, mainly affecting the rural population, the North and Northeastern regions, the black population, and women. The emergency aid had been the only social assistance provided by Brazil’s federal government to address the economic crisis of the pandemic. It was created by means of a law passed by Congress and signed by President Jair Bolsonaro.

The Pandemic Has Not Ended and Hunger Has Increased

This is what leaders, community communicators, and favela residents have concluded. Mariana Galdino, from the Jacarezinho Audiovisual Lab (LabJaca), in the North Zone of Rio, says she’s sensed there has been “a renewed demand for basic food baskets,” since “we’re not receiving emergency aid.” With the curfew announced in the capital, the “demand for food security” returned.

In twelve months, since the start of the pandemic, the price of food rose 15% on average, nearly triple the inflation rate for the period. According to the Brazilian Institute for Geography and Statistics (IBGE), the prices that increased the most were for grains, legumes, and oilseeds (57.8%). Next were oils and fats (55.9%) followed by tubers, roots, and vegetables (31.6%).

Anna Paula Salles, a 15-year leader of the Association of Women of Itaguaí—Warriors and Social Articulators (A.M.I.G.A.S.), says that “the situation is even more dire when it comes to hunger and illness.” Aside from the food shortage, she reports that “families don’t have anything to eat because they have nowhere to cook. They cook over wood fires.” For this reason, the association decided to “provide cooked meals.” According to her, “the political shifts become clear, since after the elections, politicians want to sweep the evils of the pandemic under the rug.”

Anna Paula Salles, a 15-year leader of the Association of Women of Itaguaí—Warriors and Social Articulators (A.M.I.G.A.S.), says that “the situation is even more dire when it comes to hunger and illness.” Aside from the food shortage, she reports that “families don’t have anything to eat because they have nowhere to cook. They cook over wood fires.” For this reason, the association decided to “provide cooked meals.” According to her, “the political shifts become clear, since after the elections, politicians want to sweep the evils of the pandemic under the rug.”

She adds: “Over these twelve months, one can easily see that people are dying because of hunger and violence more so than Covid. It’s totally chaotic, a genocide happening everywhere you look. People have no water, electricity, gas, or food. This is the opposite of progress.” The mortality rate in the Baixada Fluminense is 2.5 times greater than the national average.

Anísio Borba, a resident of the Complexo da Maré favelas and member of the Maré Mobilization Front, explains that not only has the ongoing Covid-19 situation worsened the numbers of cases and deaths, but it has also resulted in hunger and expanded it as part of a chain reaction. “It’s been a year and everything is worse and more absurd, because fuel is very expensive, and likewise the price of basic food stuffs is also very high.” The price of a basic food basket was 18.54% higher at the end of 2020 than the previous year (2019), which is the steepest increase since 2002, according to the Nucleus for Economic and Social Research (Nupes) from the University of Taubaté (Unitau).

In Complexo da Maré, there were two mobilization fronts. Even so, Anísio said that the donation drives are unable to cover all the families. “We had to prioritize the basic food baskets because there weren’t enough for everyone. Now it seems we’ve gone two steps backwards. We thought this was going to last three months, then six. A year has passed and here we still are,” he vented.

#PeopleAreHungry

Over the entire year since the pandemic’s onset, vulnerable populations were only able to mitigate hunger through the efforts of mobilization fronts formed by collectives, community leaders, and favela residents. It was the targeted efforts by civil society organizations in these areas that filled empty plates, since even with the emergency aid of R$600 (US$107) and, later, of R$300 (US$53.50), hunger was insatiable, just like the virus.

Collectives in Complexo da Maré, Complexo do Alemão, Jacarezinho, City of God, Providência, and others played chess with death, confronting and dodging, along with their neighbors, their chances of dying from Covid-19, from hunger, or from gunshots due to the police operations even in the middle of the pandemic. Favela residents took to the streets to denounce signs of state-sponsored necropolitics.

With the resumption of economic activities despite the population not being vaccinated, basic food basket donations tapered off in the favelas and peripheries of Rio and other cities. Now, these Covid-19 response initiatives need help. As the pandemic continues, the number of donations declines, but hunger is on the rise. According to a report by newspaper O Dia, eight in every ten families in favelas depend on donations to survive. The “Favela and Hunger” survey realized by Instituto Locomotiva, in partnership with Data Favela and Cufa, interviewed 2,000 residents from 76 Brazilian favelas in the second week of February.

On March 16, the “People Are Hungry” campaign was launched with the goal of donating basic food baskets to 223,000 families across the country to counter the pandemic’s side effect of hunger. To achieve this, the initiative’s organizers plan on raising R$133 million (US$23.6 million) through the campaign website.

The campaign is an initiative by Brazil’s Black Coalition for Rights, and is supported by various grassroots movements and NGOs, such as Amnesty International Brazil, Oxfam Brazil, Ethos Institute, 342 Artes, Redes da Maré, and Brazilian Campaign Against Inequalities (ABCD).

The campaign and the initiative by the collectives and grassroots movements are necessary contingencies in the absence of public welfare policies to enable the survival of the poorest. This Thursday, the Brazilian president signed two provisional measures that will allow the emergency aid to resume. The aid will be paid starting April in up to four installments, which vary from R$150 (US$27) to R$375 (US$67), reaching 46 million Brazilians. Only one person per family is covered, and the rules for receiving this aid are even more rigid than in 2020.

Vaccination Now!

While people die from the new virus and from hunger, a year after the official announcement of the pandemic by the WHO, Brazil is collecting Health Ministers. Over the weekend of March 13, Eduardo Pazuello resigned from the position, with Marcelo Queiroga coming in to replace him. Brazil has become a global pariah despite past recognition for successful vaccination campaigns, since aside from failing to control the spread within the country, it also lags in the process of immunizing the population.

According to the Brazilian Covid-19 vaccination map, shared on March 18, 10,984,488 people have received the first dose of the vaccine. This number represents 5.19% of the Brazilian population, according to a study performed by the consortium of media outlets based on data from state health secretariats. Ricardo Gazzinelli, president of the Brazilian Society of Immunology (SBI), in an interview with CNN, said: “It’s unlikely that the entire Brazilian population will be vaccinated against Covid-19 in 2021.” The expectation is that only in 2022, an election year, will there be a national vaccination plan that covers the entire population. Meanwhile, in the United States, 30% of the population has already received the first dose of the vaccine, with the expectation that the vaccine will be available for everyone by late May, and Chile is vaccinating 1.45% of its population every day.

The Covid-19 in Favelas Unified Dashboard—comprised of over 20 organizations and collectives that run it—and 27 partner institutions sent an open letter to the offices of Rio de Janeiro municipal councillors and state deputies, in addition to health secretaries and other public administrators, in which they demanded an immediate priority vaccination plan for favelas and the homeless population. A priority vaccination plan for low-income communities is being carried out in California, in the United States, where 40% of the doses are reserved for this group.

The “Vaccines for Favelas Now!” campaign was launched on February 10—the Statewide Mobilization Day Against Covid-19 in Favelas. Given the lack of water supply to many homes or normal access to health services, as well as the high percentages of essential and informal workers for whom social distancing is impossible, the group of allies insists that the favelas require priority vaccination.

The letter also details six ways in which municipal and state governments could prioritize favelas in the immunization efforts, stressing that essential and vulnerable workers—like drivers, couriers, security guards, gardeners, waste pickers, cashiers, cleaners, caretakers, construction workers, and day laborers—are also part of the economy’s frontline and, therefore, of the response to the coronavirus pandemic.

How Can Governments Prioritize the Favelas?

- Guaranteeing priority vaccines at health stations and family clinics within and near favelas along with the adequate infrastructure to store and distribute doses.

- Making vaccines available for a greater percentage of the adult population in favela areas.

- Prioritizing essential and vulnerable workers, such as drivers, couriers, security guards, gardeners, waste pickers, cashiers, cleaners, caretakers, construction workers, and day laborers.

- Enabling additional vaccination centers in easily accessible locations, such as near train and bus stops, as long as this is managed in an orderly fashion, without posing the risk of gatherings or getting in the way of traffic. Examples of suggested locations: sports gyms, reactivating field hospitals that have not been completely dismantled, forming partnerships with clubs, NGOs, and the like.

- Resuming payment of the emergency aid until the vaccine reaches everyone.

- Guaranteeing priority vaccines for teachers from the state and municipal public school systems in order to allow for classes to, potentially, resume safely for both education professionals, students, and their families.

*Both RioOnWatch and the Covid-19 in Favelas Unified Dashboard are initiatives of the NGO Catalytic Communities (CatComm).