This article is part of a series on energy justice and efficiency in Rio’s favelas. It is also part of a series created in partnership with the Center for Critical Studies in Language, Education, and Society (NECLES), at the Fluminense Federal University (UFF), to produce articles to be used as teaching materials in Niterói public schools.

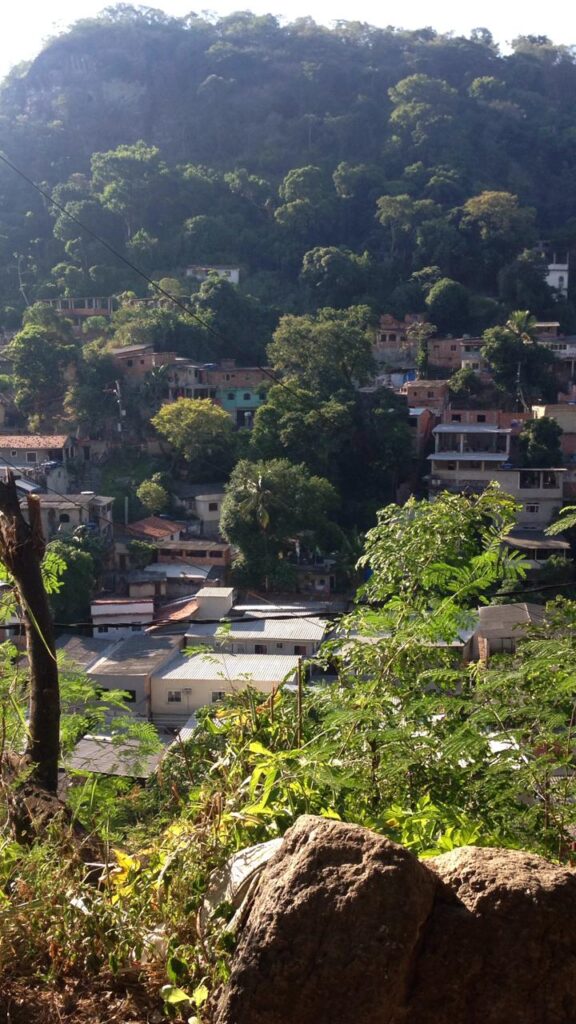

My name is Mayara Pereira, better known as Mayara Ylo, and I see daily, both within and outside of my community, the difficulties that people face to pay their bills, buy food, or afford some leisure, even more aggravated by the Covid-19 pandemic. I am a resident of the Palmeira favela, in the Fonseca neighborhood, in Niterói, Rio de Janeiro’s sister city across Guanabara Bay, where I have lived for the past 18 years. In Palmeira, we residents suffer all types of neglect and violence at the hands of the State and private actors. We suffer from the precariousness of urban infrastructure and the supply of other public services, including that of electricity.

My name is Mayara Pereira, better known as Mayara Ylo, and I see daily, both within and outside of my community, the difficulties that people face to pay their bills, buy food, or afford some leisure, even more aggravated by the Covid-19 pandemic. I am a resident of the Palmeira favela, in the Fonseca neighborhood, in Niterói, Rio de Janeiro’s sister city across Guanabara Bay, where I have lived for the past 18 years. In Palmeira, we residents suffer all types of neglect and violence at the hands of the State and private actors. We suffer from the precariousness of urban infrastructure and the supply of other public services, including that of electricity.

Our favelas are forgotten! There are many electric poles made of wood, corroded iron, and all sorts of improvisations—often made by residents themselves, and frequently financed by them—resulting in an entanglement of wires, bundled together by the hundreds, which put the lives of residents at risk to give them access to electricity, which is a right. It may look like lack of organization, but that does not stop it from being a type of energy justice for favelas. It is these entanglements of electric wires which guarantee the access to energy for millions of people who need this service in favelas and peripheries. Once again, the favela does for itself what the State chooses not to do. Residents often have to make a choice: electricity or safety?

“Favelas pay a lot for poor service. They pay a high price and get little benefit, exactly the opposite of what society, in general, thinks of electricity in favelas.”

However, contrary to what is assumed in the rest of the city, many families in favelas and peripheries pay for the electricity they consume, which is supplied legally by the local public provider, whether that is Light, in Rio de Janeiro, or Enel, in Niterói. Favelas pay extremely high (and rising) prices for electricity, and yet they continue to have an electricity infrastructure that is precarious and dangerous for residents. They pay rates and taxes on their bills which are contributions for the improvement and maintenance of power grids and public lighting, but they do not receive a satisfactory provision of any of these services in their areas.

A Badly Provided Service and Growing Prices

Many favelas suffer from almost daily blackouts, particularly in the summer, due as much to the summer rains and the precariousness of the power grid as to the increase in energy consumption from the excessive use of fans and air conditioning on the hotter days. Favelas pay a lot for a very poor service. They pay a high price and get little benefit, exactly the opposite of what society, in general, thinks of electricity in favelas.

Often, even if a home is connected to the electric provider’s grid and bills are paid on time, the company does not respond to calls and emergencies because the client lives in a favela. Nor do the companies resolve old problems in favelas which, in other neighborhoods of the city, would have been fixed in a matter of hours. In most cases, if residents do not organize themselves, they will not even have access to the service. Often, informal connections or gatos are the only way of guaranteeing a family’s access to electricity. Yet they are legally branded as theft, since the energy is being diverted without payment.

In reality, with the current increase in prices, there is a barrier between legal access to electricity and millions of Brazilian families. But what can happen to those who commit “electricity theft”? Outlined in article 155 of the Penal Code, theft can be punished with one to four years in prison, on top of resulting in the suspension of electricity provision and fines.

The pandemic and all its economic and health consequences have now added to the context described above. High levels of unemployment and a generalized decline in income complicate access to energy and food for the poorest.

“Many families have a very difficult choice to make between food and electricity, a choice which should not have to be made during a pandemic.”

It is despairing that, in the midst of the pandemic, with unemployment and hunger, we are also suffering from absurd and unjustified increases in electric bills. While various governments worldwide acted to guarantee the population’s access to electricity and water amid a generalized falls in income levels during the pandemic, nothing was done in Brazil. Here there were increases! The impact of these increases is also going to be felt in the food supply of poorer families.

The Impact of High Prices on Electric Bills: Voices from the Palmeira Favela and Others

This growing weight of the cost of electricity has come to be oppressive for some families. Many families have a very difficult choice to make between food and electricity, a choice which should not have to be made, especially during a pandemic.

Where I live, Palmeira, is a favela which is forgotten by the government and with many frustrations related to the electric supply. There are widespread accounts of unjustified increases in electric tariffs, charges of abusive interest rates when bills are paid late, as well as accounts of power cuts and failures in maintaining poles, wiring, transformers, and switchboards.

My home and my family are examples of this. I used to pay R$55 (US$10) per month to Niterói’s electricity provider, and now I pay R$88 (US$16.45). Consequently, the difference in the increase each month causes complications when I need to shop, as my income is not identical each month. I do not have air conditioning or things which require a lot of electricity to function and, even so, the bills do not stop going up, with a different increase every month. I live with my 26-year-old brother; we are both unemployed. At the moment, I take part in cultural competitions and work with online sales to keep up with the household bills, even with a variable income from one month to the next. Many people are in debt and experience difficulties to buy products.

A neighboring family, for example, the Barbozas, used to spend R$70 (US$13) per month before the pandemic, but now pay R$155.85 (US$29.13). This is an increase of over 100%! This amount could have been invested in the purchase of a propane tank or food.

The head of the household, Alessandra Barboza, 32, a day laborer and homemaker, lives with her daughter with a basic monthly income of around R$745 (US$139). With 21% of her salary going to pay electric bills and their modest habits of electricity consumption, she says: “Our comfort of having Wi-Fi and air conditioning is essential, especially for my daughter to have more leisure options. I try and make a small effort to give her the best.”

Residents of my community have, for years, been frustrated with inflation, blackouts, and the lack of infrastructure which affects families’ comfort. Local businesses always accumulate losses from stock lost in blackouts. It is common that, due to the intermittent nature of the power supply—dubbed “blinking light”—household appliances burn. Even fires caused by the precariousness of our local electric utilities—Light’s or Enel’s services—are frequent. This sad state of affairs also affects hospitals which are fundamental for Niterói’s North Zone, like the Azevedo Lima Hospital or the Fonseca emergency care unit (UPA).

Light and Enel affirm that low-income families can make the most of the Electricity Social Tariff program to get up to a 65% discount on their electric bill. To benefit from the social tariff, the family must have an income of up to half the minimum wage, equivalent to R$550 (US$103). And so I ask myself: do they not think about how hard it is to find employment right now? Do they know how expensive it is to live in Greater Rio? There are many unemployed people who are not able to pay for their electricity, not even for 35% of their consumption, much less what the Social Tariff program proposes.

Marcos Andrade, 27, resident of the Fonseca neighborhood in Niterói, has also lived in the Palmeira community for 23 years. Married and without children, Marcos works for a delivery app and has a monthly income of R$1,000 (US$186.88) to support himself and his partner, who is unemployed. They used to pay R$60 (US$11.21) per month in electricity and now pay R$89 (US$16.63) per month. Marcos notes: “with every bill, an unexpected increase. The app deliveries are not giving me much return and the little bit of each bill that increases ends up making a big difference when it comes to buying something at the market. I’m stunned with how much things have gone up: gas, electricity, food. My God, when is this going to end?”

Vania da Silva de Souza, 22, has a daughter with whom she lives in the Nova Grécia favela in the Tribobó neighborhood, in Niterói. Unemployed, she explains that she lives with the help of her father and that she spent, on average, R$200 (US$37.38) per month before the pandemic. Today, her electric bill is coming in at between R$300 (US$56) and R$400 (US$74.75) per month. “We don’t have air conditioning or anything else that uses a lot of electricity, but even so the bill has increased ridiculously, maybe because of the interest we pay on bills, that might have gone up. I have a daughter whom I look after with the help of my father, who works as a cleaner. Our monthly family income is R$925 (US$172.87) for the three of us. Even with him working in the formal market, we have problems with the excessive increases,” Vania says. With the electricity bill eating up 32-43% of the household income, these problems are in no way surprising.

Camila Carvalho de Pedroso, 29, resident of Morro São Carlos in Estácio—on the other side of the Guanabara Bay, in the city of Rio de Janeiro—is also unemployed, and only receives a R$250 (US$46.72) pension from her ex-partner. Camila explains that she used to spend R$61.30 (US$11.46) per month maximum, and that nowadays her electric bill comes in at, a minimum, R$90 (US$16.82) per month (36% of her income). “I have three children, my daughter lives with me and the other pair lives with my mother, and I am feeling the effects of the increase in bills on my income. Whenever possible, my mother helps me. In the middle of the pandemic, they have increased [the cost of] electricity, water, food, and other things. And the salaries of political leaders just keep going up, they don’t diminish. Many people who work hard all day and don’t receive fair compensation suffer from the increase in electric bills. Even when they are small, any increase makes a big difference when the time comes to buy food,” says Camila.

Months without emergency aid lay bare the federal government’s disregard for tackling the sanitary, nutritional, and economic crises caused by the pandemic in favelas, and, when added to the increase in the cost of food, gas, and electricity, reveal some of the various factors which have made life harder for poorer families. On top of high unemployment, the emergency aid came late and lasted too little. By last August, almost 60% of Brazilians had received five installments of emergency aid between R$600 (US$112) and R$1,200 (US$224) per month. After that, Congress approved a further four installments of R$300 (US$56). With the end of this policy of emergency basic income, still in 2020, many families began to go hungry and some were forced to squat or onto the street. Many were forced to expose themselves to the coronavirus on packed public transport in the search for survival.

In this context of huge and growing socio-economic inequality, where the weakest are always hit hardest, it can be said that favela residents work today to eat today, without knowing what they will eat tomorrow or even if they will have work tomorrow. Eight in ten families in favelas depended on donations of food packages in 2020. In this context, with the pandemic killing 4,000 people a day across Brazil, the exorbitant electric bills are central factors in the growing spiral that is claiming the life of our people.

Energy justice means guaranteeing everyone access to energy, with good quality service, and a price that is compatible with the consumer’s income. The favela is clamoring for energy justice!

About the author: Mayara Pereira, also known as Mayara Ylo, is a resident of the Palmeira favela in the Fonseca neighborhood, in Niterói. She completed secondary school in 2018 and currently works with delivery services. She is a part of two cultural groups in her city, the Wolf Crew, which is a collective focused on dance, and Sound Check Djs, a group of various musicians and cultural artists.

About the illustrator: Rodrigo Binarts, 38, is a fine artist and percussionist born and bred in Olavo Bilac, Duque de Caxias, in the Baixada Fluminense. Rodrigo works with graffiti and percussion at the Terra dos Homens NGO and the Guadalajara Public High School, where he coordinates the culture center.

This article is part of a series on energy justice and efficiency in Rio’s favelas.