This article is the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” Follow our Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas series here.

While I drink coffee, in the distance I hear samba and the chirping of birds. Every morning, they fly around the palm trees that cool my backyard. If it weren’t for the pandemic, this week I would surely have visited one of the busiest parts of my neighborhood a few times: Feirinha da Pavuna, or Pavuna’s Little Market. On one side of the market, you’ll find merchants and their vegetable and fruit stands. On the other, you’ll see a little bit of everything a home needs.

Right near the market, is the carnival samba school Grêmio Recreativo Quilombo Acari. It was founded in the late 1970s by composers like Wilson Moreira, Paulinho da Viola, Candeia, and Nei Lopes who were trying to break away from the big samba schools that were increasingly commercial. This history marks the territorialization of black ancestries and identities.

The Local Context

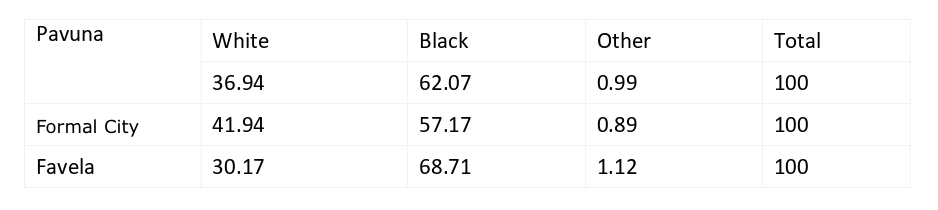

Many market regulars come from the many favelas in the surrounding area, some of which include the favela complexes of Pedreira, Chapadão, Barros Filho, and Acari. Pavuna occupies an important space in the carioca imaginary, which was built in part by the oral history of black popular culture—like in the funk tune Endereço dos Bailes—and, in part, by the media narratives of poverty and violence. It is, culturally and numerically, a black neighborhood: 62.07% of Pavuna is black, be it on the “asphalt” (the formal city) or in the favela, according to data compiled by researchers from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) based on the 2010 Census:

Personally, the market brings back the most diverse memories of childhood and adolescence in one of the neighborhoods with the lowest Human Development Index (HDI) numbers in Rio de Janeiro: 0.790. This low performance, due to public policies that are inefficient for the region, brings about different consequences for favela residents in accordance with their race and class.

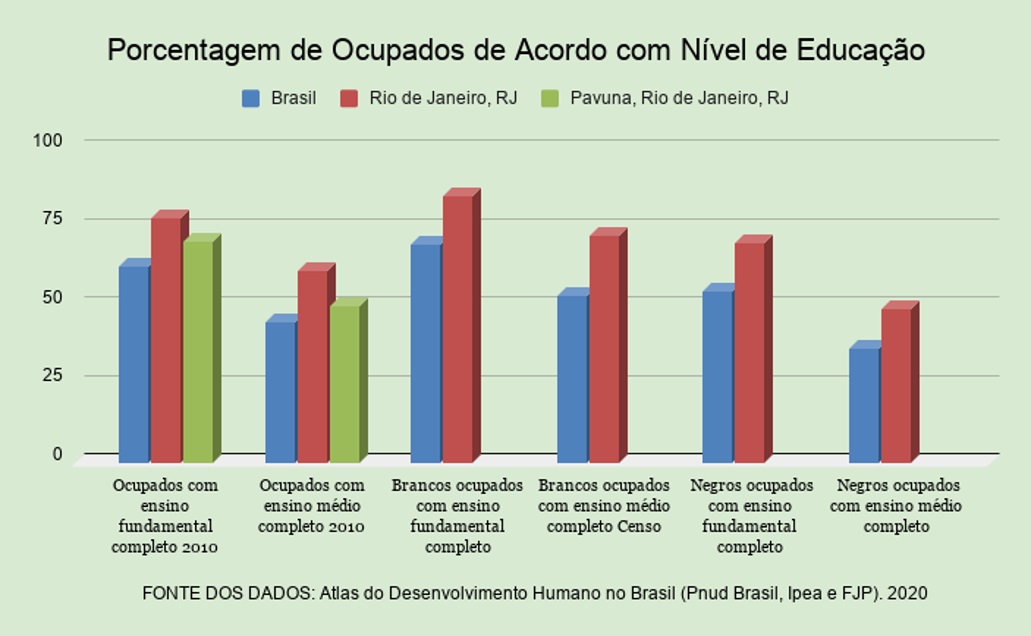

The intersectionality of inequalities between Pavuna residents is not a phenomenon isolated to the neighborhood. The city of Rio de Janeiro witnesses the same historic tendency. There are differences between black and white people in terms of job access, employability, income, and access to education. According to data from the 2010 Census, while 61.16% of workers in Rio de Janeiro formally completed high school, in Pavuna, that rate is only 50%. Lower education levels result in lower wages and limited access to opportunities. Therefore, considering the 2010 Census data included in the graph below, it is possible to affirm that the neighborhood of Pavuna, which is predominantly black, has residents with lower education levels than the rest of the city. This fact limits the employability of Pavuna residents and constrains the average income for the region, which is lower than the city at large.

Structural racism combined with limited access to education, plus low quality education in general, function as a central pillar for the reproduction of racial inequality. These conditions are convenient for their own self-maintenance, reproducing themselves and thus maintaining the status quo. It is as if the concrete in a construction beam could preserve itself, eliminating the need for constant maintenance. It is probably because the neighborhood is so unequal that it carries a history of struggle and resistance in the search for daily survival.

The neighborhood also faces high levels of urban violence, another product of the historical abandonment that also disproportionately impacts Pavuna residents who are black, poor, and from the favelas. In 2017, organizations like Fogo Cruzado, the Getúlio Vargas Foundation (FGV), and FGV’s Department of Public Policy Analysis (FGV/DAPP) found that, based on data from the Public Security Institute (ISP), the greater Pavuna area, and surrounding neighborhoods, are the most violent in the city of Rio de Janeiro. Armed violence occurs often with strong participation from the State.

Pavuna Market: Cultural Heritage

However, despite the media narrative of fear, the traditional Pavuna Market continues to be a classic image of Rio’s periphery. A little bit of everything is sold there. Diversity is the central characteristic of the market’s 298 stalls. They function practically every weekday, between eight in the morning and eight at night. According to market regular Fabio de Souza, “These operating hours are slightly longer if compared to other large markets in the city, thanks to the right to settlement granted to the locality by the city government.”

It is hard to find a person from Rio’s periphery who has never heard of this popular market due to its historical and cultural importance. Between sips of drinks, a game, a meet-up, a market stall, and a sale, it is possible to see and hear what the market has to offer. Local street businesses are approximately 50 years old and extend to the sidewalks of the neighboring municipality of São João de Meriti. The boundary between Greater Rio’s Baixada Fluminense region and the Rio neighborhood is the river that gave the neighborhood its name: the Pavuna River.

The word Pavuna originates from the Tupi indigenous language and means “place of darkness” or “dark lake”, which does not define the neighborhood in the popular imaginary. A larger symbolic mark was left by Jovelina Pérola Negra‘s samba, Feirinha da Pavuna (Confusão de Legumes), written after Jovelina witnessed a fight while passing through the market in the 1980s.

Jovelina made history in samba, becoming well known for her musical repertoire and remarkable voice. She was one of few samba artists and composers to earn recognition in a field that was male-dominated. The late singer left an enormous artistic legacy for Pavuna, despite being a resident of the neighboring municipality of Belford Roxo.

The Pavuna Market was declared intangible cultural heritage of the city in 2014, through Law 5787/2014. The pride of many local workers, who regularly sustain their family by way of their sales, the market only received this historical recognition after a powerful social media campaign mobilized by the popular culture and event space, the Arena Carioca Jovelina Pérola Negra, which is maintained by the City of Rio de Janeiro in Pavuna. The struggle of workers and residents of Pavuna was thereafter preserved.

The market is recognized not only as a place for shopping, but also as a space to socialize. Locals frequent the market, chat, make purchases, and form ties daily; businesses were built from the ties of solidarity between a population that is mostly black and migrant.

Another space that is regularly frequented in the region is Beco da Teresa, on the Pavuna River. The beco (alley) is well known for its sale of typical foods from the Brazilian Northeast and by frequenters who meet there to socialize, drink, and eat Northeastern dishes. Between one stall and another, to the sounds of forró, old friends meet up for a chat.

The Heart of Pavuna as Seen by a Market Regular, a Worker, and the Association of Informal Vendors

Market frequenter Zenaide Feitosa, 64, is a resident and a vendor in Parque Colúmbia, a nearby neighborhood. She says she has frequented the space since 1984, when she moved to the region. Recently, she has reduced her frequency of visits to the market, cautious due to coronavirus, given her age. However, Feitosa says that, every month, when she takes off a few days to go pay her bills at the bank, she stops by the market to make a few purchases.

Feitosa speaks with enthusiasm about her relationship with the market, of her memories of buying food in bulk, of a children’s playground where her girls used to play when they were little. According to her, when you cannot find what you want at a stall, you can surely find what you’re looking for at the neighboring one, highlighting the variety of products sold in the place.

Fábio de Souza, 41, tells his story as a Pavuna Market worker. Son of a street vendor, he started working at seven years old at an auto body repair shop in order to bring income home. Souza says he has worked in many parts of the city, but has never been without work. He has done a little bit of everything throughout his life to support his family. Souza has sold candied apples, sweets and varied items at streetlights and during carnival. Later, he was a street vendor with his father in Rua dos Romeiros, in Penha, and also worked on public transportation selling goods. Souza shares that he also owned a small bakery and a video store in Pavuna, but that he had to sell both due to the high rate of robberies and general price hikes, preventing him from keeping his shops open.

A taste for the art of selling, combined with the need for an income made Souza not give up on having his own business, leading him to start his first stall at the Pavuna Market in 2011. With R$300 (US$55) that he borrowed, Souza began a small fruit stand. He was able to expand it after some financial returns. Today he is proud to tell of the importance of his work in helping him employ family members like his father, wife, and father-in-law.

Souza says he has customers that come from Botafogo, Tijuca, Campo Grande, Cabuçu, and even Niterói, Rio de Janeiro’s sister city across Guanabara Bay. These customers make sure to shop in Pavuna because the prices are more affordable. “They ask me to reinforce their shopping bags because they’re coming from far away.” For Souza, the market is “the heart of Pavuna, with a significance that isn’t just economic but also social because, just think of how long we’ve been around, doing everything we can to regulate the market, to keep prices low for the customer, even when they rise too much. We lower our margin, but we keep the same prices… oil… [and other] things have doubled in price but we continue to charge only a flat rate of R$1,99 (US$0.36) per unit. And it’s not because we’re buying it cheaper! It’s because we are charging the same price. We go to the market, we wake up at dawn, we go around and around Ceasa [Rio’s Central Food Supplies Warehouse] for hours, and haggle so that we can keep the best prices possible for the residents of Pavuna and neighboring communities.”

Market vendor Cátia Santana, 47, is the current vice president of Pavuna’s Association of Informal Vendors (A.C.I.P.), an institution that aims to oversee commerce and fight for public policies that support workers of open-air community markets. She also speaks about the absence of public authorities: “Many things need to be done for us, informal workers, because we don’t get any type of assistance. We have been abandoned by the authorities… They only come here to seize goods and stalls. We need to establish partnerships with the government… we do try to organize the Pavuna Market, but we have no support. Together with the directors of A.C.I.P, we aim to give some peace of mind to informal workers.”

Santana recalls her family’s relationship with the market, spanning generations: “I started working at the Pavuna Market with my mom when I was nine. Thanks to God and the Pavuna Market, my mom raised me, I raised my son, and he’s raising his children.”

It’s possible to see, in the comments made by Pavuna Market workers Santana and Souza—both market vendors that coordinate and organize with others to ensure the survival of the market and to bring forth improvements, and dignity—a strong social and political tie with the territory, its corporealities, and its narratives. Over generations, solidarities and territorialized struggles in the peripheral space have given rise to Feirinha da Pavuna, a heritage of Rio de Janeiro’s black population.

About the author: Ingra Maciel, a resident of Acari, is 28 years old and has a history degree from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) and a postgraduate certificate in teaching the history of Africa from Colégio Pedro II. She is currently a research assistant at UFRJ’s Medialab. During her undergraduate degree she developed her research on the criminalization of carioca funk and its process of resistance, and she is currently studying carioca funk from a pedagogical perspective.

About the artist: Born and raised in Rio’s North Zone, Natalia de Souza Flores is a member of the Brabas Crew. With a degree in Graphic Design from Unigranrio in 2017, she has worked as a designer since 2015. She launched a magazine of collective comics called ‘Tá no Gibi’ in 2017 at the Rio Book Biennial. Her main themes are Afro-based, using cyberpunk, wicca and indigenous elements.

This article is the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” Follow our Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas series here.