This article is part of a series on energy justice and efficiency in Rio’s favelas and on the coronavirus and its impacts on favelas.

Brazil is experiencing a historic recession, exacerbated by the coronavirus health crisis. According to data released by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), the unemployment rate is at nearly 15%. The uncertainty of a regular salary, the decrease in informal work, and the low amount or absence of the federal emergency aid stipend increase pressure on workers who need to ensure financial support for themselves and their families.

Among the difficulties generated by the pandemic and the need for social isolation is the increase in the price of cooking gas (LPG). In April 2019, Economy Minister Paulo Guedes stated in an interview that the amount paid for gas would be reduced by half in two years. At the time, the average price of the cylinder was R$69.42 (US$13.63). Two years later, the gas cylinder is being sold for over R$100 (US$ 19.63) in some capitals, and recently, on June 14, cooking gas once again increased by almost 6%.

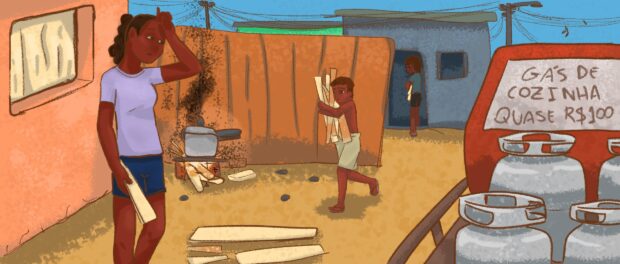

Changes in Petrobras management, international oil prices, and fluctuations in the exchange rate of the dollar explain the rise in gas pricing. Antony Devalle, director of Rio de Janeiro’s Oil Workers Union (Sindipetro RJ), explains that, “Brazil is a large oil producer and has the installed capacity to produce many oil products and to, basically, produce them in Brazilian reais. However, the Investment Partnership Program’s (PPI) policy favors oil product importers [with prices in dollars] and the privatization of the Petrobras (national oil company) system, especially its refineries. As a result, the cost of gas cylinders weighs on the poor and many families are having to improvise with alternatives such as firewood and kerosene, both very risky. Although Brazil has continental dimensions, it is predominantly a country that depends on its roads. More expensive diesel means more expensive food and, therefore, more hunger.”

National Mobilization for Access to Cooking Gas

This situation led the Unified Federation of Oil and Gas Workers (FUP) and its unions to carry out actions where they offered cooking gas cylinders for less than half the average amount being charged across the country, within the scope of the “Fuel at a Fair Price” campaign, in partnership with the Central de Movimentos Populares (CMP) and other local organizations. The mobilizations took place on April 29, in eleven cities.

In Rio de Janeiro, the “Fuel at a Fair Price” campaign promoted an action with the sale of gas cylinders for R$40 (US$7.85) in Quilombo da Gamboa, in the Port Region, an area of the city that carries ancestral symbolism. Some 180 gas cylinders were sold, serving 180 of the region’s families.

View this post on Instagram

Phrase on poster: The Quilombo da Gamboa accessible housing project reaffirms that Black Lives Matter! Yesterday, today, tomorrow, and always. Stop killing us!

Instagram post: Solidarity Action was held yesterday at the Quilombo da Gamboa Occupation. In a partnership with CMP, 180 gas cylinders were made available at R$40.

According to FUP, “the main objective of the ‘Fuel at a Fair Price’ campaign is to alert the population about how the policy adopted by Petrobras in October 2016, based on the Import Parity Price (IPP), which has been affecting not only fuel prices but also causing a ripple effect of rising prices in other sectors of the economy, such as food and transport.”

In this scenario, the ones whose lives have been seriously impacted are peripheral people like Regina Célia Batista, 44, resident of Morro da Aparecida, in São João de Meriti, in Greater Rio’s Baixada Fluminense region. Batista, who feels the impact of the pandemic in its various spheres, says: “I believe the government really needs to intervene to bring these prices down. We are living in a degrading way; firstly, because we can’t eat properly, and now we can’t afford to buy gas. Here, in São João de Meriti, gas costs around R$82 (US$16) up front. If it’s delivered to your house, it’s even more than that. I know a person from Bangu, who had to cook food on a wood stove because they had no money to buy gas on a certain day. There are a lot of people who can’t eat with the amount paid by the emergency aid. I wasn’t lucky enough to get it, I didn’t make the list. Many families don’t have bread and milk to feed their children. As a solo mom, being jobless and with no income for seven months, I live off odd jobs. It’s difficult for so many Brazilians. Our country is experiencing an epidemic of poverty too.”

In this scenario, the ones whose lives have been seriously impacted are peripheral people like Regina Célia Batista, 44, resident of Morro da Aparecida, in São João de Meriti, in Greater Rio’s Baixada Fluminense region. Batista, who feels the impact of the pandemic in its various spheres, says: “I believe the government really needs to intervene to bring these prices down. We are living in a degrading way; firstly, because we can’t eat properly, and now we can’t afford to buy gas. Here, in São João de Meriti, gas costs around R$82 (US$16) up front. If it’s delivered to your house, it’s even more than that. I know a person from Bangu, who had to cook food on a wood stove because they had no money to buy gas on a certain day. There are a lot of people who can’t eat with the amount paid by the emergency aid. I wasn’t lucky enough to get it, I didn’t make the list. Many families don’t have bread and milk to feed their children. As a solo mom, being jobless and with no income for seven months, I live off odd jobs. It’s difficult for so many Brazilians. Our country is experiencing an epidemic of poverty too.”

Community Mobilization for Gas in Morro da Providência

At the beginning of the pandemic, in March 2020, Cosme Felippsen—activist, favela tour guide, resident of Morro da Providência and creator of the historic Rolé dos Favelados favela tour—lost a large part of his income due to the cancellation of tourism activities. With the sudden drop in income, he was left without resources to buy gas for his family and had to rely on the solidarity of a friend.

In March 2020, Felippsen and his neighbors created the SOS Providência Covid-19 Crisis Committee. He says that, at the time, in the community’s WhatsApp groups, committee members often heard complaints about a shortage in cooking gas, and received reports that some families were using charcoal to make fires and cook their food. It was from these claims and from his own experience that Felippsen realized that the actions of donating basic foodstuffs and hygiene items were not enough, as gas was also needed to cook that food. Based on this reality, SOS Providência created the campaign “Gas for the Women of Providência.”

The campaign’s first action was organized by Rolé dos Favelados in August 2020 with the goal of delivering R$100 (US$19.47) to 100 women in Morro da Providência. Through dissemination and registration via social media and WhatsApp, the action managed to raise R$6,879.03 (US$1339.63) and serve 66 women, 77% of whom were black or brown, with only 1% having higher education.

The day the cooking gas funds were given out, the women selected by the “Gas for the Women of Providência” campaign got an extra bonus with lectures by prominent black women. Guest speakers were: architect, urban planner and municipal councilor Tainá de Paula; artist Dayse Gomis; and Rute Sales, one of the founders of the Movimento Moleque. Several members of the Mothers of Manguinhos movement were also present.

The second action of the “Gas for the Women of Providência” campaign took place in November 2020, this time organized as a broad partnership of SOS Providência member groups, namely: Rolé dos Favelados, Casa Amarela, Rio Memória Ação, and Galeria da Providência. The action involved 100 women. The meeting, for the delivery of a R$100 (US$19.47) aid for gas, featured lectures by guests: Deize Carvalho, founder of the Pavão-Pavãozinho and Cantagalo Victim Mothers Center; jongo singer and poet Jessica Castro; poet Isadora Gran; and social worker and pastor Viviane Azevedo. Several members of Mothers of Manguinhos were also present.

The second action of the “Gas for the Women of Providência” campaign took place in November 2020, this time organized as a broad partnership of SOS Providência member groups, namely: Rolé dos Favelados, Casa Amarela, Rio Memória Ação, and Galeria da Providência. The action involved 100 women. The meeting, for the delivery of a R$100 (US$19.47) aid for gas, featured lectures by guests: Deize Carvalho, founder of the Pavão-Pavãozinho and Cantagalo Victim Mothers Center; jongo singer and poet Jessica Castro; poet Isadora Gran; and social worker and pastor Viviane Azevedo. Several members of Mothers of Manguinhos were also present.

Hugo Oliveira, coordinator of SOS Providência and a resident of Providência since he was a child, says that seeing so many families benefitting from the campaign made him feel both joy and indignation: “Joy for being able to strengthen some of the women who watched us grow up and who serve as a reference for us, directly and indirectly; women who are our friends’ mothers, aunts and grandmothers. Joy for having the opportunity to give back to our territory some of the affection and care we received while growing up. [This] keeps a sense of community alive. The indignation comes from watching a government too incompetent to serve the neediest and to see very little, if anything, be done to care for and protect a part of the population that supports the base of the social structure. Once again, we have to be the ones to face police operations and exposure to the virus so that we don’t let our community struggle.”

Silmara dos Santos, 33, mother of two teenagers and one of the beneficiaries of the “Gas for the Women of Providência” campaign, recounts what it has been like to overcome the financial crisis with the help of community organizers: “With this unemployment crisis, we’ve been having a hard time finding work. Difficulties come up every day; it’s not just about not having cooking gas, we also have many other concerns. It was very gratifying to have this great help from Rolé dos Favelados. I managed to make food for my children. For us, women from Providência, it was also wonderful to participate in that beautiful lecture about women.”

Silmara dos Santos, 33, mother of two teenagers and one of the beneficiaries of the “Gas for the Women of Providência” campaign, recounts what it has been like to overcome the financial crisis with the help of community organizers: “With this unemployment crisis, we’ve been having a hard time finding work. Difficulties come up every day; it’s not just about not having cooking gas, we also have many other concerns. It was very gratifying to have this great help from Rolé dos Favelados. I managed to make food for my children. For us, women from Providência, it was also wonderful to participate in that beautiful lecture about women.”

To raise awareness, the “Gas for the Women of Providência” campaign created the yellow pamphlet with tips on saving cooking gas.

SOS Providência is currently launching a broader campaign, which aims to act along four pillars: territory, health, education, and solutions. Discover and support the campaign here.

The Romanticization of Poverty and the Naturalization of Precariousness

The arrival of the pandemic brought to light existing problems such as the deterioration of public health care, and reactivated historical problems such as hunger. Even with the imminent risk of being contaminated by Covid-19, many Brazilians are subjected to crowded public transportation, scarce individual safety equipment, and especially the dehumanization of the individual. A study done in 2019 and published by IBGE showed that 75.2% of the nation’s poorest are Afro-Brazilians. Therefore, we can deduce that the majority of those harmed by the increase in cooking gas prices are Afro-Brazilians.

With more than 8,000 followers on Instagram, Joyce Salvador, a resident of the Olavo Bilac neighborhood in Greater Rio’s Duque de Caxias and a solo mother of two, receives daily messages from favela mothers narrating the reality they are living in these pandemic times:

“I live at my grandfather’s house, my income comes from the advertising I do, but what keeps me going is the R$375.00 (US$73) emergency aid I get. Many people close to me talk about saving gas by buying an electric stove to bake or heat up food, which just makes the electricity cost more. In general, the media only show what they want about the favelas and poverty. These media portray the underprivileged as helpless. We get by as best we can.

Every day, I get messages in my [social] media from black mothers who are completely uncertain about what they’re going to serve the following day. Do you really think any mother wants to wake up at dawn and make lunch that will only be ready at noon, on a stove using wood that is harmful to the lungs? The answer is clear and obvious: no. We want a minimum of comfort for our family.

During the social isolation period, I relied on the help of the foodstuffs provided by Baixada Fluminense collectives such as Movimenta Caxias, and I am not ashamed to get them. I only have two children, and for women who have five or more children, one basket of food per month is definitely not enough. We need to stop romanticizing what is not romantic at all.”

Roberto Gomes Iberu, CMP-RJ state coordinator and a resident of Santo Cristo—who took part in the “Fuel at a Fair Price” campaign, in April, in Quilombo da Gamboa—also spoke about the romanticization of the struggle for survival of the city’s economically vulnerable population, which leads to the naturalization of precariousness:

“In this period of great world chaos, especially in the so-called ‘Global South’ countries, we observe how cruel it is when we hold the subjects themselves responsible for building their own destiny. We know that it’s not quite like that in a capitalist society, and why not say, one that is also profoundly affected by structural racism. There is no dignity in seeing entire families on the streets of big cities, scavenging for cardboard to guarantee their daily meals. Many [individuals] think it’s ‘beautiful’ to see such a scene in the streets, but they don’t recognize that the State doesn’t fulfill its role.

Even within the capitalist system, those less fortunate need to have a minimum amount of money to live with the least amount of dignity. We often hear that money doesn’t bring happiness, but whoever reproduces such a fallacy has never lived in abject poverty, but rejoices in saying the poor have to accept their lives as they are. With the arrival of the pandemic, this romanticization has become more evident. News stories in different media make a point of emphasizing how ‘beautiful’ it is to see entire families living on the streets, cooking their food on the corners and under marquees. Is something like this really natural?”

Energy and Social Aspects of Household Gas

Cooking gas, liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), is the result of refining crude oil and underground gas, and is basically composed of propane and butane. Since it originates from petroleum, its energy source is not renewable. Gas has great applicability, with a high calorific power, and when compared to other sources derived from petroleum, has a lower environmental impact. A study done by the National Union of Liquefied Petroleum Gas Distribution Companies (Sindigás) showed that more than 95% of the country’s population used LPG in 2011, being more common in homes than running water and electricity. This piece of information alone demonstrates the importance of this type of energy.

Cooking gas, liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), is the result of refining crude oil and underground gas, and is basically composed of propane and butane. Since it originates from petroleum, its energy source is not renewable. Gas has great applicability, with a high calorific power, and when compared to other sources derived from petroleum, has a lower environmental impact. A study done by the National Union of Liquefied Petroleum Gas Distribution Companies (Sindigás) showed that more than 95% of the country’s population used LPG in 2011, being more common in homes than running water and electricity. This piece of information alone demonstrates the importance of this type of energy.

Alessandra Gonçalves, 23, an Industrial Chemistry undergraduate at the Rural Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRRJ) currently living in Greater Rio’s Seropédica municipality, explains how studies about cooking gas go beyond the traditional subjects of physics and chemistry:

“I believe that interdisciplinarity is the best way to look at this, since the increase in cooking gas prices is related to historical, geographical, and even sociological issues. This would give us a better way of evaluating the impacts of this event more generally, so as to understand it in its entirety, visualizing all the influences and details and, finally, analyzing the consequences generated. Furthermore, I believe that it’s not only the amount being paid for gas and the reasons behind this that should be taught, but rather, various other study areas such as the constitution, financial education, sustainability, sexuality, inflation, and many other subjects.

We become adults who know the quadratic formula, but don’t learn about our civil rights and duties, or about what an elected representative is supposed to do. Adults without critical thinking who, as a consequence, accept the conditions imposed by the government. According to the constitution, all power emanates from the people. So, how is it possible that a people who suffer so much are still on the hunger map? Our representatives make a killing and steal fortunes and, unfortunately, the most interesting thing for them is that we are still a people without a holistic view of our country, that we continue to wear invisible blinders.”

About the author: Born and raised in Vilar dos Teles, São João de Meriti, Beatriz Carvalho is a journalist, media-activist, feminist, and founder of Mulheres de Frente.

About the contributor: A resident of Morro da Providência, Cosme Felippsen is a tour guide and creator of Rolé dos Favelados, a tour that has taken more than 7,000 people to learn about the history of Morro da Providência. He also coordinates the SOS Providência Crisis Committee that is currently launching a broader campaign, which aims to act on four pillars: territory, health, education, and solutions. Learn about and support the campaign here (in Portuguese only).

About the artist: Anna Paula Rodrigues is a freelance designer and illustrator, with a degree in industrial design from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). Anna Paula—who focuses on anti-racist topics relating to aesthetics and beauty—works as a graphic designer in numerous Rio de Janeiro NGOs.

This article is part of a series on justice and energy efficiency in the favelas of Rio.