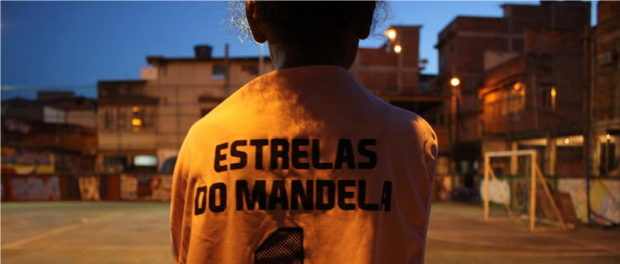

The Brazilian soccer player most frequently considered the best in the world is a woman. Still, the sport is often viewed as a masculine activity throughout the country. Actions that challenge such norms are therefore fundamental in building a more egalitarian society. This is the case of the women’s soccer team Estrelas do Mandela, a project active in the favelas of Complexo de Manguinhos, in the North Zone of Rio de Janeiro. Founded in 2002, the initiative seeks to promote the sport within favelas as a tool for social transformation. Beyond directly empowering the 60 students on the team—both on and off the field—the project offers social assistance in surrounding communities.

Estrelas do Mandela is coordinated by Graciara da Silva, better known as Gagui. Born and raised in Manguinhos, she was a student of the project and is currently a physical education teacher. Her admittance to university opened many doors for her, but the struggle for the recognition of women in this space began long before. “I already had experience in women’s soccer and with all the barriers we’ve had to overcome to strengthen ourselves in this domain… Fighting sexism, fighting the indifference through which our potential is underestimated, and the sexualization of women’s bodies in such a male-dominated space. This is a barrier that we continue to struggle to overcome,” says Gagui.

The presence of a former student on the front lines of the initiative has a powerful influence over the students; in their coach, they see possibilities of a future for themselves. “The girls can see themselves through me, because I was a rebellious girl, and no one believed I’d amount to much. But my desire to change through sports made a huge difference in my life,” Gagui shares. After being a part of Estrelas do Mandela, she played for other teams and had her first professional experiences with the sport.

In the past 19 years, the demands of the territory and of the students served by the project have changed, also leading to adjustments in the project. In the beginning, participants were women and girls between the ages of 14 and 35. However, the rising number of younger students getting pregnant motivated the coordinators to take action and confront this hard reality. “There were 16-year-old girls in the program who were already on their second pregnancy. At that rate, they’d be on their third pregnancy in no time. This was something that worried us a lot,” explained Gagui. From then on, the initiative began to work with children and adolescents aged 5 to 17, aiming to make structural changes in this scenario through awareness-raising activities about early motherhood, the place and the rights of women, and their life plans. “We work directly with women’s empowerment through sports. We want them [the students] to have a perspective for their futures, for where they want to be in life,” says Gagui.

The Manguinhos complex is made up of 12 favelas, including the communities of Mandela, where the project began, and Mandela II, where the weekly practices of the women’s teams currently take place. In addition to sports training, the project offers complementary school tutoring sessions twice a week. Reading workshops are also held for the younger girls, using a bibliography of black authors to empower the little ones: “This is extremely important because the typical student in our group is a black child, often without a present father, with kinky hair, dark eyes and skin, and too shy to say her own name. We aim to supplement their education with the workshops we offer. This is even more important today, because education in Brazil during the pandemic has become very fragile, with no way to supplement online classes,” emphasizes Gagui.

The Manguinhos complex is made up of 12 favelas, including the communities of Mandela, where the project began, and Mandela II, where the weekly practices of the women’s teams currently take place. In addition to sports training, the project offers complementary school tutoring sessions twice a week. Reading workshops are also held for the younger girls, using a bibliography of black authors to empower the little ones: “This is extremely important because the typical student in our group is a black child, often without a present father, with kinky hair, dark eyes and skin, and too shy to say her own name. We aim to supplement their education with the workshops we offer. This is even more important today, because education in Brazil during the pandemic has become very fragile, with no way to supplement online classes,” emphasizes Gagui.

A Red Card for Sexism

Before getting to where she is now, Gagui shares her long journey in search of visibility, partners, and recognition both in and outside of the favela. At first, the project depended solely on volunteers and donations were scarce. Things began to change when the project underwent formalization and internal organization. Gagui explains that, “We succeeded in centralizing our objectives and began to dedicate ourselves to raising money: with crowdfunding, donation pages…We also got fixed partners. We have a really cool partnership with Ace Projects, which works by training leaders and also helps us directly by hiring a tutor and an administrator for the project.”

Another challenge confronted is the sexism that is always present on and off the field. The repetition of offensive comments and jokes by community members exemplifies the challenge of overcoming the collective image of soccer being a strictly male sport. “The sexism was blatant from the moment we started using the field at the same time every week. When we claimed the space as also ours, we began to suffer attacks. Some would stand off the court mocking the players, ‘they can’t play, they’re no good…’ saying stuff that was really hurtful,” says Gagui.

In Gagui’s eyes, these comments are part of the reproduction of a patriarchal structure already rooted not just in favelas, but all of society. “This is all a clear form of sexism being reproduced by children. It’s already ingrained. Can you imagine what kind of men they will become, if they can’t even share a soccer field? So, we begin by taking direct care of the girls in the project, by way of female empowerment,” explains Gagui, emphasizing the necessity to work for gender equality in favelas, with the inclusion of boys in this discussion.

To improve the project’s facilities, the team behind Estrelas do Mandela is organizing a fundraising campaign to build a kitchen in the second half of 2021. The space will allow the cooking and delivery of snacks to students. “Today, we have a large room where the project’s court is, but it is also the space where our workshops and school tutoring activities take place. We can’t mix our books with the food. We already have the space; we just need some help to build. We already have a drinking fountain, but we don’t have anywhere to install it. This will increase the quality of the services we offer our students and our ability to receive teams from outside [the community],” explains Gagui.

Dribbling the Impacts of the Pandemic

When Covid-19 arrived, the project became a vector of social action beyond sports. The initiative of solidarity began last year, when some of the students’ mothers brought up the financial difficulties they were facing at home. “We went to our social media and asked for help. From that point on, we received support from organizations like the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz). Together, we created a food distribution campaign called Solidarity in Manguinhos. This was great because we created a direct relationship with the people responsible for our students, so, we were also growing stronger,” says Gagui.

After this first food drive, other partnerships appeared, allowing the project to aid a larger public. “Today, we also distribute food to residents of 12 communities. In other words, this campaign doubled the number of communities we reach with the support given to our students. In addition to Manguinhos, we now serve Jacarezinho, Maré, and adjacent communities.”

After this first food drive, other partnerships appeared, allowing the project to aid a larger public. “Today, we also distribute food to residents of 12 communities. In other words, this campaign doubled the number of communities we reach with the support given to our students. In addition to Manguinhos, we now serve Jacarezinho, Maré, and adjacent communities.”

One of the project’s largest partners at the moment is the Gerando Falcões network, that selected Estrelas do Mandela for the distribution of digital foodstuffs baskets in the form of food vouchers, in the amount of R$150.00 (US$29) per month, for two months. This campaign has already impacted 200 families, and will soon be expanded to 250 families. “This form of help gives the person the opportunity to buy what they need. We seek to bring dignity to favelas as much as we can, and this effort allows the person to eat what they’d like to eat. We see the happiness and joy of those who receive this aid,” Gagui says proudly.

According to Gagui, the project’s biggest dream today is to fulfill its vision: to be a reference project in Manguinhos, promoting health, a good quality of life, and the well-being of the students and their families—reaching as many communities as possible: “Our mission is to better the socioeconomic lives of the people who live in favelas, who have to deal with so many stereotypes. We fight to overcome the criminalization of poverty. We want our project to be a mirror for other projects, in communities that live a reality comparable with ours. We want to produce human dignity. Solidarity is what keeps the favela going.”

According to Gagui, the project’s biggest dream today is to fulfill its vision: to be a reference project in Manguinhos, promoting health, a good quality of life, and the well-being of the students and their families—reaching as many communities as possible: “Our mission is to better the socioeconomic lives of the people who live in favelas, who have to deal with so many stereotypes. We fight to overcome the criminalization of poverty. We want our project to be a mirror for other projects, in communities that live a reality comparable with ours. We want to produce human dignity. Solidarity is what keeps the favela going.”