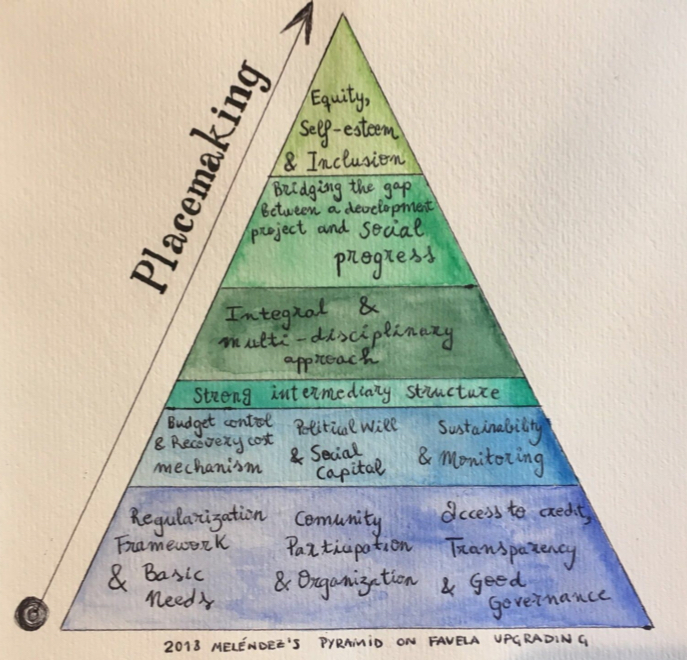

This is the final article in a six-part series on the application of Meléndez’s Pyramid for Favela Upgrading to the city of Rio de Janeiro and its favelas. This pyramidal concept was conceived by the author of this series in order to achieve more coherent and sustainable results in favela upgrading. Inspired by Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, the pyramid consists of ten blocks, each representing a group of indispensable elements. Based on multidimensionality, interdependence, and simultaneity, the pyramid addresses the physical, political, economic, social, cultural, and psycho-emotional aspects of favelas.

This sixth article addresses the psychological and emotional components often overlooked in the planning of favela upgrades. Read the full series here.

The last two blocks of Meléndez’s Pyramid for Favela Upgrading address psychological and emotional components, too often overlooked in the planning of favela upgrades. These last two levels are: bridging the gap between a development project and social progress, and the production of inclusion, equity, and self-esteem among favela residents.

Very often, favela conditions expose residents to a range of vulnerabilities that undermine human flourishing. Roofs and walls do not guarantee a home any more than buildings guarantee either spaces or cities. Therefore, favela upgrading needs to address the embedded, sometimes intangible, aspects that hamper full human development.

Urban planners Ivo Imparato and Jeff Ruster described it as “closing the gap between a development and a social project.” Drawing from their ideas, our pyramid proposes bridging the gap between a development project and social progress. This transition can only take place when upgrading processes address psycho-emotional components, thus inspiring proactive attitudes that favor development. When a project does not turn into social progress, it is ignoring the human dimension of it all: the fact that development is inherently about people.

Firstly, bridging the gap is about analyzing community structures and working alongside residents to address shortcomings. In addition, obstacles to social progress must be removed (stereotypes, sexism, gender-based violence and lack of female empowerment, low literacy, lack of education, lack of environmental awareness, etc.). These steps are essential, since negative habits can hinder the autonomy acquired through physical development.

For social progress to be attained, placemaking needs to be an important element. Our identities are shaped by the areas we inhabit. Therefore, bridging the gap is about encouraging residents’ realization of their inherent value and transformative power, through both a springboard (previous pyramid levels), and specific psycho-emotional initiatives (the last two pyramid blocks).

Since where we live shapes us, favela upgrading must assert its social mission of fulfilling human dignity. As ecological urbanists Mohsen Mostafavi and Gareth Doherty describe, urban planners should act as the “doctors of the city.” This way, urban planning and upgrading ensure respect and development of favela lives, humanizing them. This sensitization enables society to improve, include, enhance, acknowledge and value both the worth and potential of favelas.

The tip of our pyramid is an intrinsically emotional one, encompassing the production of inclusion, equity and self-esteem. These elements must be achieved transversely across the upgrading cycle, and topped off at the end, once more urgent aspects have been fulfilled.

Inclusion, equity and self-esteem emerge via the establishment of networks that enable, among the residents of Rio de Janeiro’s favelas, a sense of belonging in their city. Physical, economic, social, political, psychological and emotional components, guaranteed through supportive networks—which can be formed across favelas themselves but ideally involve society at large–would grant them access to a more equitable city life, fighting social stigma and encouraging social cohesion.

In practical terms, the urban elements that most contribute to generating feelings and realities of inclusion, equity and self-esteem are public spaces, cultural and educational projects, and dignified public transport.

For their part, public spaces can bring about citizen interactions on a more equal footing, breaking stereotypes through coexistence. Public spaces are conducive to community building, solidarity networks, improved self-perceptions and pride. In this sense, many favelas of Rio are great placemakers. By fighting the criminalization of public spaces, residents have made places to share and coexist. Such are the cases of Complexo do Alemão’s EDUCAP and the transformation of the Realengo viaduct into a green park.

Regarding education and culture, Rio de Janeiro has a natural advantage given its diverse and rich grassroots culture. Notwithstanding a chronic municipal lack of provision for culture, relevant cultural initiatives aiming to change favela narratives continue to thrive. For instance, Pavuna’s Grafitti museum, Cantagalo’s Teatre-se and numerous other grassroots solutions.

Lastly, quality public transportation implies the literal inclusion, equalization and acknowledgement of favela residents. According to planner Daniela Fabricius, there are over 10,000 informal vans operating in Rio de Janeiro (vs. the city’s bus fleet of 8,700). This fact underscores a public disregard for many urban areas. Public authorities should fulfill their duty of providing for the people, designing public transport initiatives that dignify people’s time.

So far, they have given priority to marketing over functionality. For instance, the Complexo do Alemão cable car, with its enormous costs and which required the eviction of residents to create a multi-stop transport system, was “for the English to see“—built leading up to the 2016 Olympics but abandoned shortly after.

Neglecting these emotional components results in incomplete, unsustainable or irrelevant upgrades. Rio must realize upgrades in ways that actually boost residents’ quality of life and self-esteem.

Favela life is a survival strategy, one that has produced tireless work and collective resources in an attempt to overcome public sector neglect. As such, favela life is a vindication of rights, a critique to the present system, demanding a more inclusive, equitable, and esteem-based Rio de Janeiro.

In conclusion, through placemaking, our pyramid calls for a change in the favela narrative, in a process in which the whole city must partake. This process involves a rejection of stereotypes and an effort to comprehend favela realities, humanizing them. Upgrading favelas should be about focusing on the objectives of residents, and on how to provide them with support, structures and capacities to realize their aspirations.

This is the final article in a six-part series.

Natalia Meléndez Fuentes is an MSc candidate in Building and Urban Design in Development at the Bartlett Development Planning Unit at University College London. Her research looks at urban informality learnings and the psycho-emotional elements of favelas and favela upgrading, mainly in Latin America.

*Catalytic Communities (CatComm) is the NGO that realizes both the Sustainable Favela Network and publishes RioOnWatch.