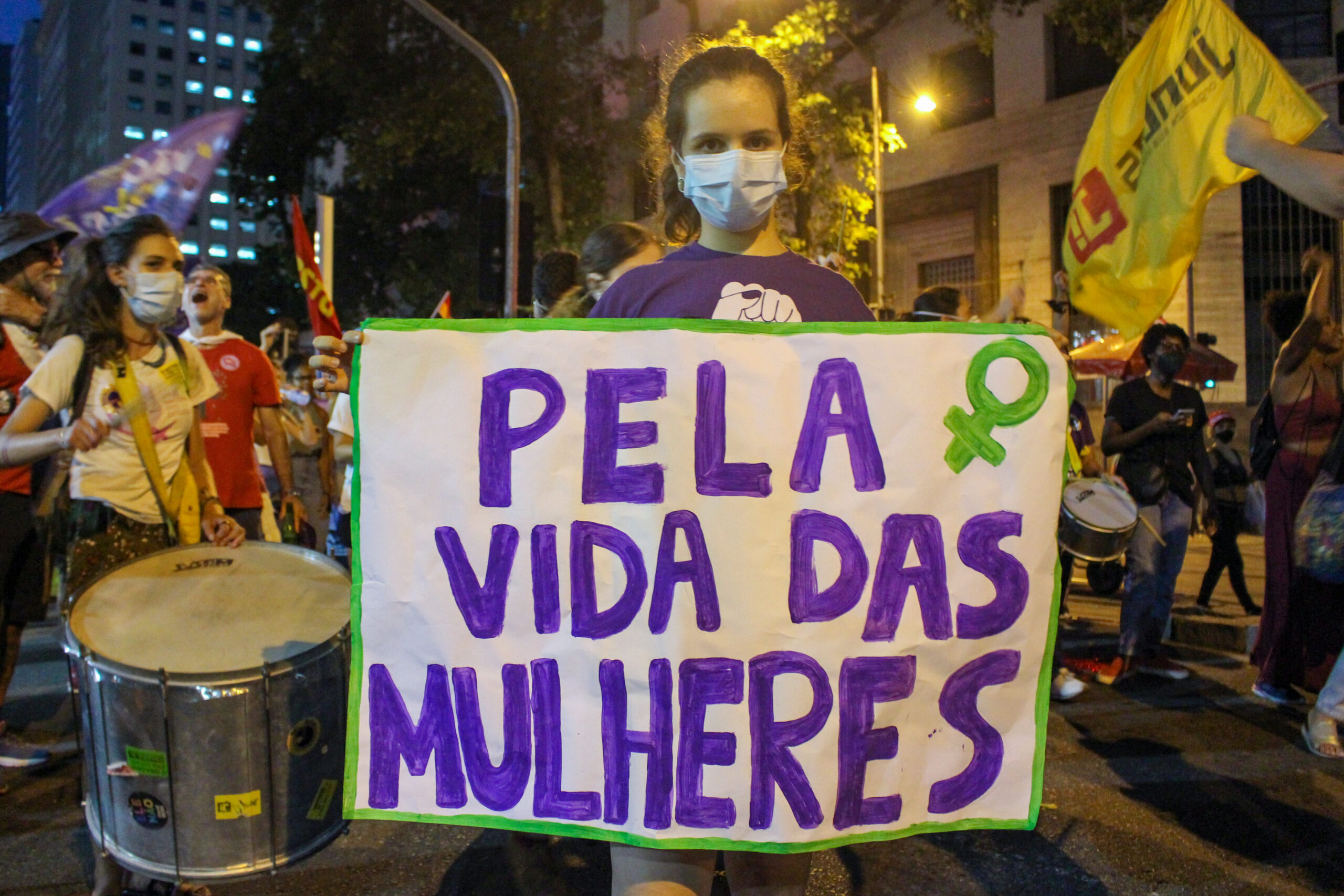

One week ago, after two years of pandemic restrictions, the International Women’s Day march once again took Brazil’s streets on March 8. There were protests in at least 40 cities. In Rio de Janeiro, the meeting point was Praça da Candelária, in Central Rio, marching down Avenida Rio Branco to Cinelândia. The slogan “No More Hunger and Violence: Bolsonaro Never Again!” was repeated on signs, in chants and speeches made from atop sound vehicles.

Due to the pandemic, March 8 rallies were exclusively virtual for the past two years. Returning to the streets, women brought with them a broad agenda of demands, ranging from the decriminalization or legalization of abortion—a traditional agenda for the movement—to the consequences brought on by the pandemic, which had different impacts on men and women, white women and black women. The event brought together women from the countryside and the city, indigenous women, trans women, transvestites and many children.

8M, as the date is known, is a moment of celebration but, above all, of struggle. Violence, unemployment and hunger affect women unequally—particularly black, indigenous and LGBTQIA+ women. It is no accident that the first item on the agenda of struggles, listed on the call for the act, is the protection of women’s lives.

In Brazil, violence against women happens primarily in the home. The pandemic left women more exposed to domestic violence, with women spending more time within the family environment. Side by side with their aggressors, many felt isolated enough not to report them, bringing on dire consequences.

The 2021 edition of the Brazilian Forum on Public Safety‘s report, Visible and Invisible: The Victimization of Women in Brazil, found that nearly six million Brazilian women reported having received threats of physical violence: being slapped, shoved or kicked. Furthermore, according to the survey, eight women were physically assaulted per minute in the country in 2020. According to the 2021 edition of the Brazilian Public Security Yearbook, almost 4,000 women were murdered that same year. In other words, on average, Brazil kills one woman every two hours. The situation escalates for trans women and transvestites: Brazil kills more transsexual people than any other country in the world.

Politics in the Everyday Lives of Women

Signs also protested the militarization of life, expressed on banners against the war between Russia and Ukraine and recalling São Paulo state deputy Arthur do Val’s recent problematic remarks. After what was allegedly a humanitarian aid trip to Ukraine, do Val—who until then was pre-candidate to São Paulo’s governorship—stated in an audio leaked by Brazilian media that Ukrainian women are “easy because they’re poor.“

Arthur do Val was not the only politician targeted. President Jair Bolsonaro and Rio Governor Cláudio Castro were also mentioned on banners and speeches given from the sound vehicle. Indigenous women carried signs opposing the so-called “marco temporal,” a case that has been set for ruling by the Brazilian Supreme Court (STF) and that, if approved, would return the frontiers of indigenous lands to only those territories occupied by Brazil’s native peoples in October 1988, when the Federal Constitution was enacted. For indigenous representatives, the case prevents the demarcation of new indigenous lands and ignores violations that took place in the period since the signing of the 1988 Constitution, including expulsions, the contamination and death of entire villages, the expansion of agribusiness and deforestation, for instance.

From atop the sound vehicle, an indigenous leader recalled the arduous battle Brazil’s native peoples have been fighting against the federal government, which has been undermining legislation that protects indigenous villages and guarantees rights and basic services to indigenous people, leaving them vulnerable to hunger, disease, invasions and violence. The weakening of Funai, the country’s key agency for the protection and assistance of indigenous people, was also highlighted.

Marielle Alive and Present!

Yesterday, March 14, marked four years since the murder of Rio City Councillor Marielle Franco and her driver, Anderson Gomes. To this day, the investigation, with myriad comings and goings, now on its fifth police investigator, has not been able to unveil who ordered the city councillor’s murder. The politician, a black, LGTBQIA+ woman, born and raised in the favelas of Complexo da Maré, worked closely with the black, women’s and favela movements. Marielle was remembered in speeches, flags, banners and signs.

Activists from Casa Nem, an organization that takes in and offers shelter to LGBTQIA+ people living in social vulnerability in Rio, also took banners in memory of the councillor.

Unemployment and Social Vulnerability

Historically, unemployment has always affected women more, but the Covid-19 pandemic worsened this scenario, widening the gap between women and men even further. If we take into account solely the working age population, 55% of men are occupied while the rate is 40% among women. During the worst phase of the pandemic, in the third trimester of 2021, the figure reached 39%.

These data were taken from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics’ (IBGE) last Continuous National Household Sample Survey (Continuous PNAD).

Brazilians saw their income shrink during the pandemic. With fewer job offers and basic products getting increasingly costly, life in cities became more expensive. Although this context affected everyone, women were left more vulnerable than men. Black and brown women were harder hit than white women, since the pandemic exacerbated Brazil’s social inequalities and issues rooted in structural racism. With children out of school and daycare due to the pandemic, household chores and childcare increased women’s workloads, taking them away from both the formal and informal job markets, and affecting their income.

Protecting the Life of Women

The mobilization around International Women’s Day is one of the most important on the calendar of feminist struggles in Brazil. Even if the context might limit reasons for celebration, the march is a moment for honoring the power of female self-organization, mobilization and empowerment, a space where all women are welcome: “This is for the protection of the lives of all women, today and forever!”