In a week of extreme violence in the city of Rio de Janeiro, a series of incidents have caused shockwaves across social media, shining a harsh light on the grave security situation and social and racial inequalities in the city and provoking intense debate as citizens seek a safer Rio.

Violent Clashes in UPP Communities

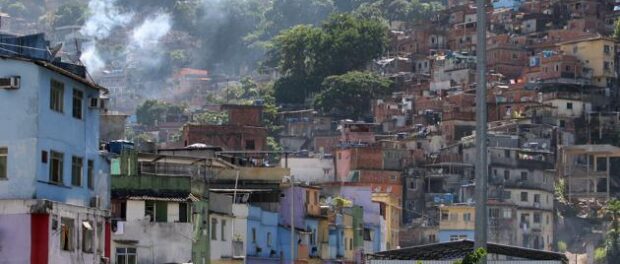

Last Friday morning, January 31, 33 year-old machine operator, Edilson Rodrigues da Silva Cardoso, stepped out to smoke a cigarette in front of his home in Rocinha and was shot in the chest and died as a shootout ensued between police and drug gangs in the Pacifying Police Unit (UPP)-controlled South Zone favela. Just five days earlier on Monday January 27, also in Rocinha, 16 year-old Thales Ribeiro de Souza was killed from a gunshot wound in the back. Neither had any involvement in the drug trade.

In his column for Jornal do Brasil, community leader Davison Coutinho wrote: “What is happening, what do the governor and security secretary have to say to these families and this terrorized community? I’m eager to hear the apologies. Will it be that the victims are judged as criminals once more? After all, someone murdered in the favela is a criminal and on the asphalt [formal city] is a victim.” There has been no official public statement or apology regarding the deaths.

Violent clashes between police and drug gangs in UPP controlled territories continued over the weekend with shootouts in Rocinha, Complexo do Alemão and Vila Cruzeiro. On Sunday February 2 in Parque Proletário in Vila Cruzeiro, UPP police officer Alda Castilho, 22, was killed with a gunshot to the head and one police officer and two residents were injured. The community Facebook page, Vila Cruzeiro-RJ, posted updates throughout the tense day, including sharing a resident’s video of UPP police apparently shooting at random, providing information for those wishing to return safely home and denouncing the first news reports which neglected to report that residents had been wounded. The following day Vila Cruzeiro-RJ posted “Enough of violence!!! We want peace and social services, as Vila Cruzeiro is totally abandoned.”

The death of a police officer tends to provoke a severe response from Rio’s security forces and after Sunday’s confrontation the state security secretary, José Mariano Beltrame, announced operations in 12 areas where the drug faction allegedly responsible for Castilho’s death are active. On Tuesday morning, February 4, in one such operation in Morro do Juramento, North Zone, six people were killed and four injured. Simultaneous police operations took place in Santa Cruz, Vila Kennedy and the Baixada Fluminense.

Reactions to Latest Police Operation

Shocking images of the violent operation in Morro do Juramento instantly started circulating online. The Facebook page PMERJ FEM, an unofficial Rio military police portal, circulated images of the bodies and bloodstained stairway with the comment “The response to the deaths of soldier Castilho and soldier Rocha [killed in an attempted robbery in Marechal Hermes on Saturday February 1], both killed at the weekend, is being given.” The post and seemingly clear positioning of the military police in executing revenge killings was denounced widely on social networks by community and human rights commentators. The post was later removed.

The images have circulated by some with comments such as “a good criminal is a dead criminal” and “human rights are for right humans,” reflecting an attitude which serves to justify police killings in Rio. Commenting online, community photographer and activist, Raull Santiago posted “The police declares war/revenge on national television, enters the favelas killing at random, spilling rivers of blood in the alleys and lanes… Meanwhile the hypocritical, alienated, accommodated society applauds with praise this type of action, legitimizing the hate, death and chaos.”

The legitimacy and legality of Tuesday’s police actions are being called into question. On Wednesday forensic doctor Leví Inimá de Miranda publicly declared he believed the police carried out executions and sabotaged any possibility of forensic inquiry by taking the bodies to hospital. Speaking to O Globo, he said: “I can affirm that the men photographed were already dead and, therefore, there are broad indications of execution. In other words, they removed the corpses to disturb the scene.”

Favela residents have long denounced such illegal actions and violence by police in communities and continue to speak out. In an article published last week in the Maré newspaper O Cidadão, community journalist and activist Gizele Martins wrote: “We will never be quiet while there are poor, black favela residents being exterminated. What we want is to have the right to the city. We want the right to exist, to be, to live, to feel part and not on the margin of this system that just controls and kills favela residents every day.”

Attack by “Justiceiros” in Flamengo

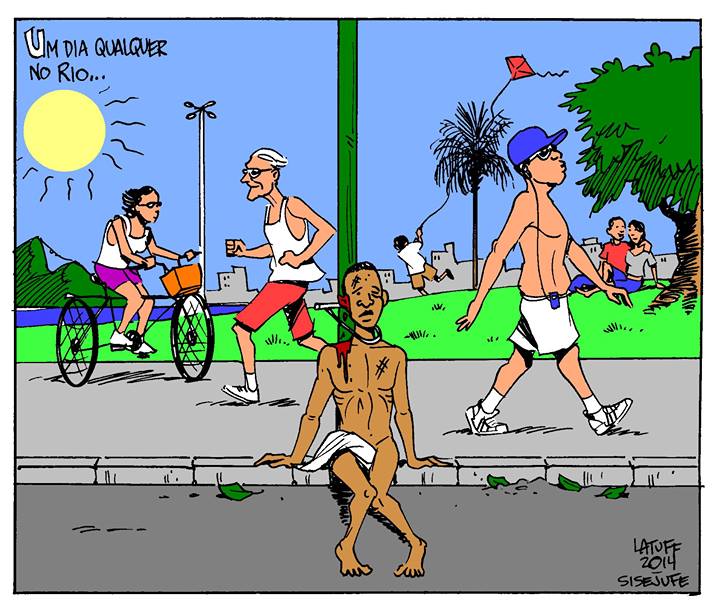

Another violent incident this last week which has shocked many and generated a furious debate took place in the South Zone neighborhood of Flamengo. Last Friday night, January 31 a group of white, middle class youths tortured a black, homeless young man suspected of robbery and clamped him naked to a lamppost with a bicycle lock around the neck. The image rapidly circulated on social networks and the group of so-called “justiceiros” responsible have been variously praised and condemned in a highly contentious moral debate.

Another violent incident this last week which has shocked many and generated a furious debate took place in the South Zone neighborhood of Flamengo. Last Friday night, January 31 a group of white, middle class youths tortured a black, homeless young man suspected of robbery and clamped him naked to a lamppost with a bicycle lock around the neck. The image rapidly circulated on social networks and the group of so-called “justiceiros” responsible have been variously praised and condemned in a highly contentious moral debate.

Many residents of neighborhoods like Flamengo, where crime and muggings have increased in recent months without any effective security response, have publicly applauded and defended vigilantes taking “justice into their hands,” revealing a chilling undercurrent of fear and hate. Comments responding to the incident on Twitter include: “It’s not barbaric, it’s preventative self defense by society against vagrants;” “That’s what you have to do with these sons of bitches;” “He should have been killed;” and “Feel sorry for him? Take him home then.”

Such comments have not been restricted to social media. On Wednesday, TV news anchor on the SBT national network, Rachel Sheherazade, said, “In a country that suffers endemic violence, the attitude of the vigilantes is comprehensible… The counter-attack on bandits is what I call the collective legitimate defense of a society without a State against a state of unlimited violence.” Her diatribe has been widely shared and criticized, including by the Rio de Janeiro Union of Journalism Professionals who released a statement denouncing the “symbolic violence of the recent comments” in which Sheherazade “violated human rights, the Children and Teenagers’ Statute and advocated crime.”

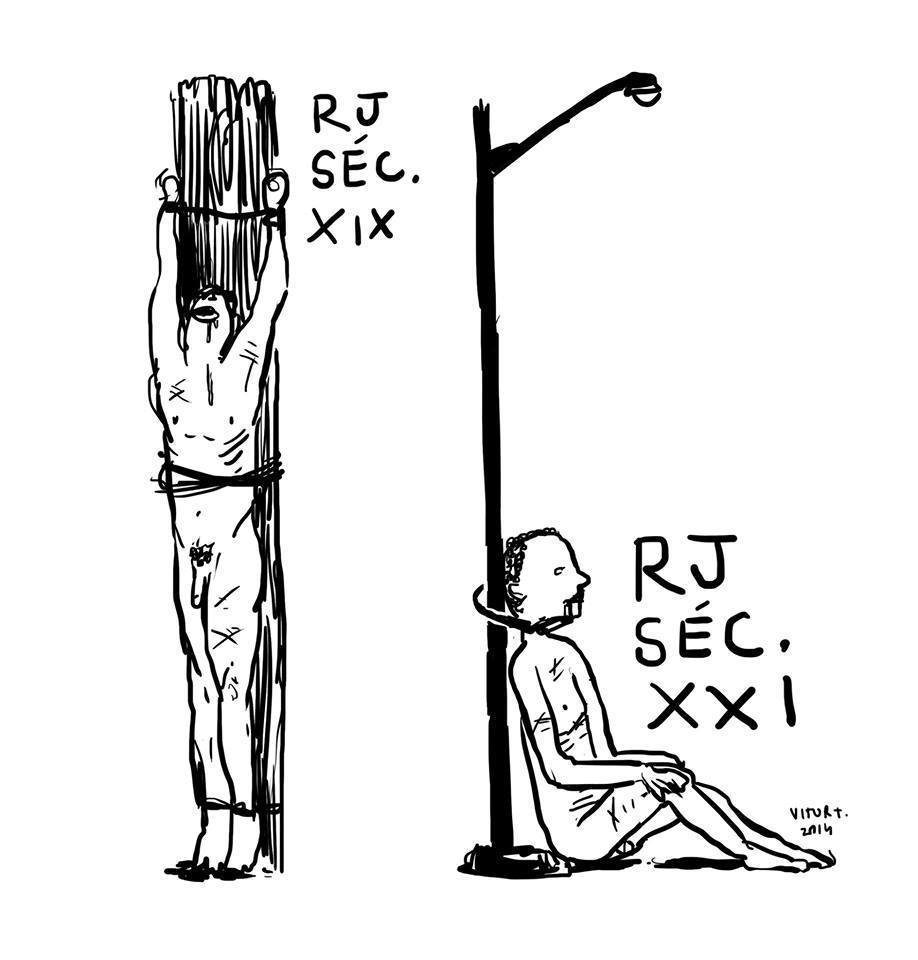

Many, including favela activists and human rights defenders, have also been vocal in their shock and outrage over the incident and subsequent commentary. Many comments have pointed to a continuation of Brazil’s brutal past of slavery, with images comparing the youth clamped to a lamppost to violent 19th century slave punishment. One such image carries the caption “Racism always confuses itself with justice to act.” In a popular Carta Capital article being shared widely on social media, journalist Matheus Pichonelli writes: “This country which applauds capital punishment is the same that ignores a historic question: the lashing is the cause, not the consequence, of the tragedy–and this wasn’t abolished with the end of slavery.”

Many, including favela activists and human rights defenders, have also been vocal in their shock and outrage over the incident and subsequent commentary. Many comments have pointed to a continuation of Brazil’s brutal past of slavery, with images comparing the youth clamped to a lamppost to violent 19th century slave punishment. One such image carries the caption “Racism always confuses itself with justice to act.” In a popular Carta Capital article being shared widely on social media, journalist Matheus Pichonelli writes: “This country which applauds capital punishment is the same that ignores a historic question: the lashing is the cause, not the consequence, of the tragedy–and this wasn’t abolished with the end of slavery.”

The clear racial and class dimensions of the crimes and tragedies of the last week have been highlighted by prominent Rio academics commenting on the events. Communication and culture professor and commentator, Ivana Bentes, posted: “There is only one war in Brazil: against the poor! Fascist and racist wave in neo-enslaving Brazil. It’s the same bio-power theater, power over the life and bodies of blacks and poor people: brutalizing, destituting the humanity, animalizing, slaughtering, humiliating and transforming into an object of hate. The ‘justiceiros’ imitate the police who for their part slaughter and massacre using race and social group as capital punishment criteria.”

Noted public security expert Luiz Eduardo Soares published a post outlining the hypothesis that the torture and clamping naked of a young black man by a group of white, middle class youth is an unconscious reaction to the “rolezinhos” of recent weeks which “dramatize democratic migrations, eliminating borders between the center and periphery, displacing the violent and iniquitous primacy of class and color.”

Not only are questions of class and race essential in the analysis of recent events and Rio’s broader security problems, but also the culture of impunity that makes such violent incidents possible. In Rio, impunity seemingly extends to both the thieves who commit daily robberies in Rio’s wealthier neighborhoods and the police and drug gangs who kill in the favelas. In this gaping absence of an effective system of justice, revenge–as practiced by the justiceiros and the police in the last week–comes to be seen as a viable substitute.

Speaking about the recent events at the Rio de Janeiro State Legislative Assembly on Tuesday, Human Rights Commission President and State Deputy, Marcelo Freixo warned against mistaking revenge for justice, and called for extensive debate of what has happened. He said: “It’s at this moment that I reaffirm the defense of a culture of rights for all. From the police officer that needs better working conditions to any one of these young people who are left over from the work market society, who never had the right to come and go, to education. It’s not by confusing justice with vengeance that we will build a democracy. These examples must be exhaustively debated in private and public schools, parliament, churches, to say what model of society we want.”

Certainly the violent incidents of the last week have sparked intense debate in the media, online and in bars, offices and streets across the city. That the events have generated societal discomfort, profound scrutiny and public debate is a promising indication that the conditions and culture that allow violence to continue can change and Rio can finally move towards a much longed-for safer future for all.