Between August 5 and 21, over the course of the Olympic Games, 92 shootouts took place in Rio de Janeiro, leaving at least 31 dead and 51 injured due to armed conflict, according to data from Fogo Cruzado (Crossfire)–an app launched in July by Amnesty International to track shootings in Rio via user-contributed reports.

The violence experienced in many of Rio’s favelas during these two weeks was not unprecedented, nor did it take place in isolation. Since 2009, when Rio de Janeiro was chosen to host the Olympics and Paralympics, Amnesty reports that over 2,600 people have been killed by police in the city–more than three quarters of whom are young, black men. Even prior to the Olympic preparation process, Rio’s mega-event militarized security program began to take shape in anticipation of the 2007 Pan-American Games and 2014 World Cup. Repeating the pattern observed in advance of both previous mega-events, extrajudicial killings escalated with the advent of the 2016 Olympic Games.

Amid concerted efforts to divert media attention and control public acts of political protest, social media offered a powerful platform for residents of favelas afflicted with Olympic violence to project their voices. Many seized the opportunity to denounce a public security apparatus that prioritizes the safety of foreigners at the expense of the lives of residents of favelas.

In the early morning of August 3, just two days before the opening ceremony of the Olympics, a mega-operation was carried out by both the Civil Police and Military Police in Complexo do Alemão, in Rio’s North Zone. Independent media group Coletivo Papo Reto of Complexo do Alemão recounted the situation via a Facebook post:

“Before 6am, residents were searched at different entrances of the favela. Around 6:30am, an armored vehicle enters the hill and houses shake, while we are awoken by the tremendous sound of the armored aircraft, flying so close to the houses that it seemed like it was going to land on one of them. This is the reality in the favelas, different violations and the police as the only public policy. Just when you think it can’t get any worse, they send more police. The participation of the favela in the OlimPIADAS [wordplay between “Olympics” and Portuguese for “joke”], is to have our life militarized, to live with the containment of poor classes, under the rifle of the State.”

Throughout the day, Papo Reto shared photos of homes invaded during police searches, sent by residents.

In addition to Alemão, North Zone favelas Acari, Borel, Del Castilho, Manguinhos, and Maré; West Zone favela City of God; and South Zone favela Cantagalo experienced intense police operations during the period in which the Games took place.

In the midst of tension in City of God, the gold medal won by judoka Rafaela Silva was widely celebrated as source of pride and inspiration for the community. On August 8, resident of City of God and actor Ricardo Fernandes posted: “Yesterday, in City of God, there were gunshots, rushing and despair. Today we have the first gold of the Brazilian Olympic team. And this gold came from a black girl, resident of the City of God favela, the same favela that had gunshots, rushing, and despair…”

Rafaela’s win was celebrated with a parade through the community a few weeks later. On the day of the celebration, resident of City of God and filmmaker Wagner Novais posted:

“When the match stopped, the shootout continued… Everyone knows that we are in a space of exception, this isn’t anything new… It was beautiful to see the eyes of residents beaming with admiration for someone who was raised in the favela and, still in the face of great adversity, overcame it and won. This and other similar stories inspire, but we don’t live only by them, it’s the exception that confirms the rule.”

On August 10, residents of Alemão were awoken to the sound of gunshots–a phenomenon which has become routine in recent months. Thainã de Medeiros of Coletivo Papo Reto shared an audio clip of shots being fired, captioned: “Gold medal in shooting #Rio2016 #OlympicCity.”

That same day, at the entrance of Vila do João in Maré, a National Force soldier was shot in the head and killed. The incident, which garnered widespread media attention, was cited as a justification for a series of police operations that unfolded in Maré over the course of the week.

Community media group Maré Vive posted a resident’s “report from the frontline” the following day:

“Helicopter flying low, window intensely shaking. The day becoming light. The streets taken by the silence and by armed vehicles, war tanks. Tension. Favela da Maré. Army, Special Operations Police Battalion [BOPE], National Force. Public Security… Olympic City. Back to the streets. I cross paths with the BOPE. Lead medal in breaking down doors. Back home. On TV, ‘live’ coverage of police surrounding the community. We’re in the media. A place to be avoided. I go to the window, first floor. The helicopter angles towards Vila do João. Ministry of Justice. Took the wrong route. Was shot… suspects identified. Hot coffee, cold wind. We hide in the shadow of fear. Horizon. Behind the helicopter, Christ the Redeemer, Pedra da Gávea and the Sugar Loaf. Tourist attractions. A smiling reporter. Close the window, the tank is coming…”

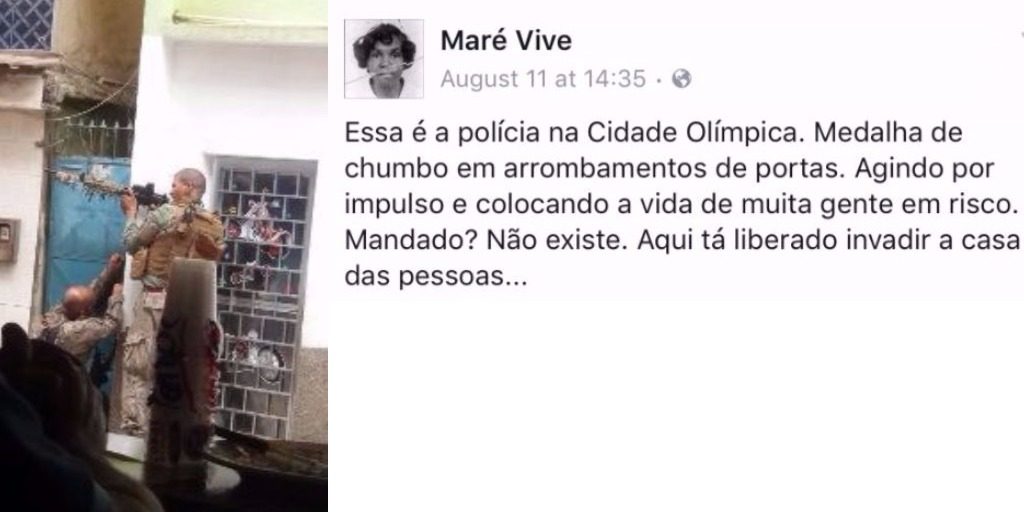

Despite constitutional protections against home invasions without a warrant (except in exceptional judicially sanctioned circumstances, according to Article 5, Section XI), residents of Maré reported frequent rights violations. Maré Vive posted a photo of two camouflaged BOPE officers, one aiming his rifle and the other appearing to meddle with the gate to a house, with the caption: “This is the police in the Olympic City. Medal of lead in breaking down doors. Acting on impulse and putting the lives of many people at risk. Warrant? There isn’t one. Here, invading people’s homes is allowed.”

On the same day, August 11, Maré Vive shared a post by photographer Bira Carvalho, describing the “everyday Olympic Games” of living in a militarized space:

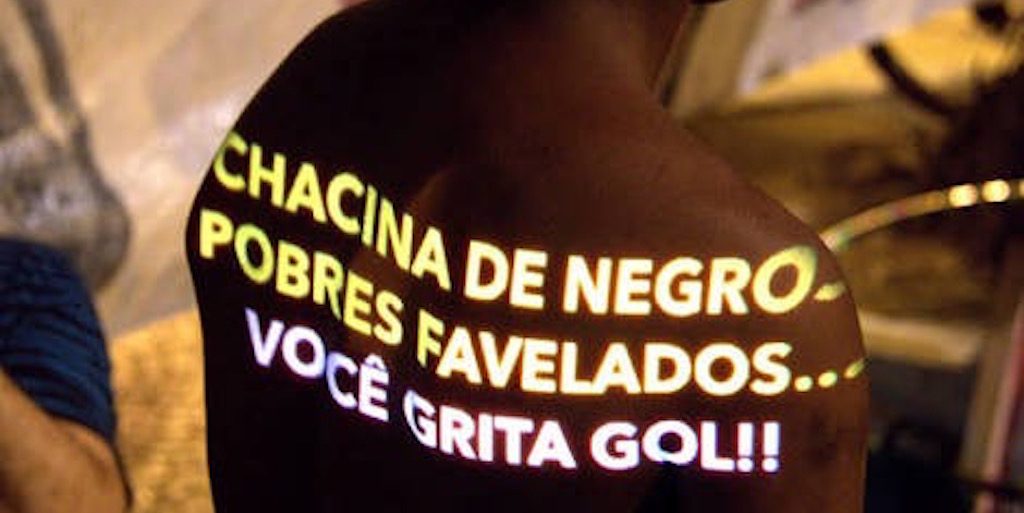

“100, 200 meter dash to save your own life, one detail, a shooting team has yet another uniform, there’s black and there’s camouflage, but here, the targets are not black silhouettes, here they are black people, living or dead from fear. I thought that like in ancient Greece, the Games were a way of bringing peace, of avoiding war. However here, that didn’t work.”

Community journalist Gizele Martins of Maré posted: “‘Olympic climate’ on the asphalt and ‘climate of war and fear’ in the favela. We are paying with life so that you can have fun! A war invented by the State!”

Also on August 11, an operation by the Military Police Shock Battalion in the Bandeira 2 favela in Del Castilho left three young men dead–ages 14, 15, and 22. Photographer Carlos Coutinho of Coletivo Papo Reto captured the scene the following morning with blood streaming down the road. Papo Reto shared the photo with the caption: “Only the blood of black, poor people from the favela flows!”

On August 16, a second intense operation was carried out in Maré. The operation left three people dead, without so much as arrest warrants in their names. Maré Vive recounted the ensuing chaos:

“Up to now, the toll has been five people dead, some shot and thousands of people impeded from working, studying, scared, terrorized, with their homes invaded… The name of this is genocide, extermination, massacre, abuse. And no one says anything… Within the favelas of Rio de Janeiro weapons are not lacking. We need to live!”

That same day, Raull Santiago of Coletivo Papo Reto posted:

“Never forget that ‘police operations against the war on drugs’ and ‘stray bullets’ only exist in specific places in our city. It’s in the favelas and peripheries that our homes and our bodies are found by the rifles that shoot racism, prejudice and exterminate our people daily, majority black and northeastern, with the justification of repressing drugs. Operations against the war on drugs is the violent control of a certain population and the ‘stray bullet’ is an instrument of extermination.”

Camila Santos of Complexo do Alemão posted a tribute to Darlene da Silva Gonçalves, a 43-year-old woman shot and killed by a stray bullet on August 18: “People crying in Copacabana… For the gold. And us, crying here in Complexo do Alemão, for the bloodshed of yet another innocent person. Rest in peace Dona Darlene.”

On August 19, in the face of yet another day of intense shootings in Complexo do Alemão, Coletivo Papo Reto posted a video of “the city at war” captioned: “While some celebrate, here we try to survive! Audio sent by a resident, a short clipping of the intense war today. Yesterday, a resident was injured and another died, found by those ‘stray bullets’ that only exist within the favelas. This needs to stop!!!!”

Following Brazil’s redemption against Germany in the mens’ soccer final, resident of Complexo do Alemão Mariluce Mariá de Souza posted on Facebook:

“I really wish we were as good in the quality of education, healthcare, security, policy, etc. Tomorrow everything returns to how it was before, our dear athletes will go back to the countries in which they live and we will remain here with our problems as always.”

Among spectators at the Maracanã stadium on August 20 was Carlos Henrique do Carmo Souza, father of 16-year-old Carlos Eduardo da Silva de Souza, known as Carlinhos–one of the five victims gunned down by 111 bullets in Costa Barros in November 2015. In an act of peaceful protest, Carlos Henrique held a banner over the stadium railing with the faces of the five boys killed by police fitted within the Olympic rings, reading: “Rio, for 450 years the Olympic champion in assassinating black youth.”

Ana Paula Oliveira, whose 19-year old son Jonatha was killed by police in May 2014, shared a photo of Carlos Henrique’s demonstration at Maracanã, writing: “I wish that this full Maracanã stadium would shout against the extermination of black youth. Indifference also kills.”

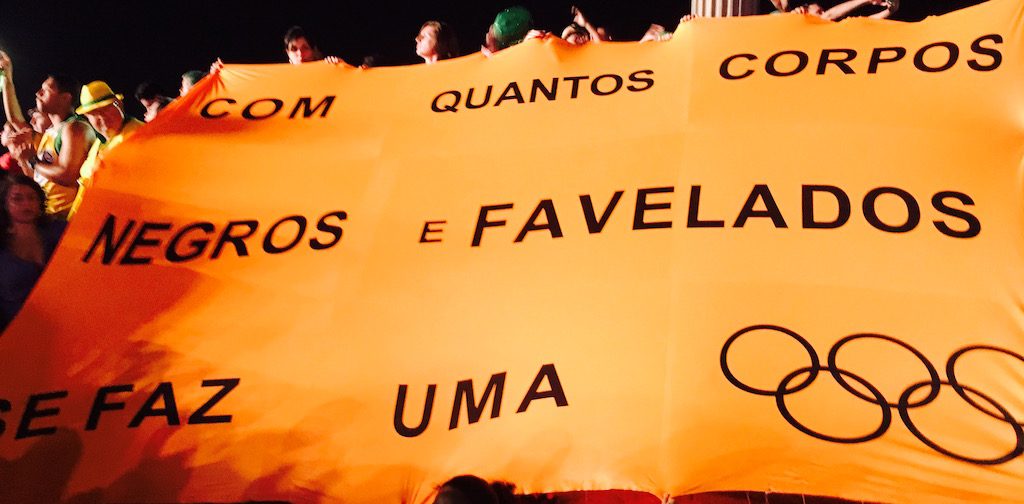

Also on game day, residents of favelas and supporters took to the streets to carry out the first act of the social media-initiated #HungerToLive campaign at Praça Mauá, in the Port Region, in an effort to draw attention to the atrocities committed under the pretext of guaranteeing security during the Olympics. Demonstrators raised a large bright orange banner reading: “How many bodies of black favela residents does it take to make the Olympics?”

Reflecting on the closing ceremony, Acari resident Buba Aguiar wrote a Facebook post criticizing the narrative of Rio as an imperfect-but-beautiful host city, unashamed of its flaws, propagated by some Olympic officials:

“The evils of Rio de Janeiro have been exposed to the Olympic audience not by the organizers of the celebration, but by the people afflicted behind the scenes, who were at no time invited to the event, and on the contrary, who were asked to remove themselves from the scene. We, residents of favelas, during the Olympic Games, were attacked in innumerable forms by the State and its armed wing in our territory. And yes, it was us who denounced the evils, just as it was also us who showed everything good that there is in our favelas.

A few days after the closure of the Games, on August 23, Thainã de Medeiros posted a graphic from The Intercept Brasil with data on violence during the Olympics, commenting: “Great! The 107 shootouts, 34 dead, 58 injured helped to keep 90% of tourists safe! An important detail is that of the 34 dead, six were security agents and of the 58 injured 28 were public servants, in other words, the ‘security police’ didn’t even serve the very agents of the State. This is a choice, the option here is clear: investment in war in poor areas to secure the rich. It doesn’t matter who dies. We’re replaceable.” (The Intercept data includes the two days prior to the opening ceremony within its date range, thus differing slightly from the previously cited numbers from Fogo Cruzado.)

In the aftermath of the Rio 2016 Olympics, international media reflect upon the Games–some celebrate the evasion of a catastrophe wrought by Zika or terrorism, others evaluate the costs incurred: Were the Olympics successful? Was the city safe? Was it worth it? The approximate 85,000 security agents deployed throughout Brazil–including 21,000 military personnel endowed with policing powers in Rio–are due to patrol tourist corridors through the Paralympics and until at least the municipal elections in October. Meanwhile, the militarization of urban space in many of the city’s favelas will continue to be experienced as an Olympic legacy extending far beyond these weeks of sport and revelry.

“They achieved everything with perfection,” Complexo do Alemão resident Zilda Chaves posted, “Only they didn’t manage to put an end to the ‘bullets found’ in black bodies in Rio de Janeiro.”