For the original by Thiago Jansen in Portuguese for O Globo click here.

In addition to being a Comlurb employee, Alexandre is a pai-de-santo (male priest of Umbanda, a primary Afro-Brazilian religion), and approaches his work with naturalness.

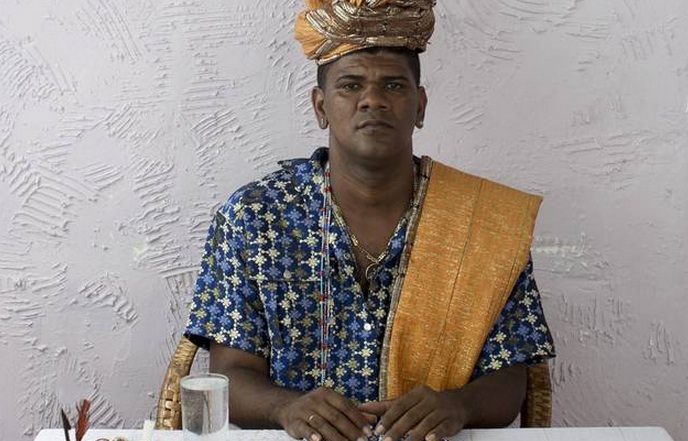

RIO—His name is an actor’s name. His nickname, a singer’s. Thus, his holiness could be no other than the hunter of axé (energy) Oxóssi, Afro-Brazilian diety of abundance, linked to the arts. Known as Emílio by his work colleagues—for his likeness to the musician Emílio Santiago who died last year—the city street sweeper Alexandre Borges, 31 years old, is famous in the Municipal Urban Cleaning Company of Rio de Janeiro (Comlurb) for the specialized work he carries out in the neighborhood of Alto da Boa Vista. Official priest (he pertains to the Umbanda Union of Afro-Brazilian Cults), father Xande is responsible for clearing the offerings left every day in the area. Source of chills for some, the work, which he must do and is a true team effort by Comlurb during the New Years’ celebrations on Copacabana Beach, is done fearlessly by the waste collector-priest throughout the year. He just considers the activity part of his professional obligation—and he does it with all due respect to the deities.

“I’m not afraid. I am only doing my job. I ask for forgiveness before cleaning up the offerings, and I leave those which are more recent to be cleared later. Disrespecting the saints would be if I kicked the macumbas (offerings), made jokes. Since it is done with respect, there is no problem with cleaning the remains,” confirms the pai-de-santo, who has been a Comlurb employee for five years under management of the Muda sub-neighborhood, which, by coincidence or fate, is located on Holy Spirit Cardoso Street.

Traditional place of offerings well before Mayor Eduardo Paes sanctioned it as such on December 18, 2013 with the Law of Axé, which guarantees that materials used in religious cult ceremonies not be included in the Zero Trash program, the neighborhood of Alto da Boa Vista has always attracted devotees who wish to give thanks or make requests. According to Alexandre himself, the popularity of the place as a focus of offerings is due to its proximity to nature—sky, trees, forest, and waterfalls.

“The saints like fresh air. Also, the elements of nature symbolize the deities, so an offering to Oxóssi, for example, needs to be close to the forest,” he explains, further indicating that the type of offering also varies according to the entity and the goal. “I’ve even found a R$100 note left for the saint. It’s the beggars in the area that do well.”

Strangely, the physical cleaning done by the priest is difficult. At 3:30am, when the majority of Rio residents are still sleeping, Alexandre is already on his feet in the municipality of Mesquita, in Baixada Fluminense, leaving his home to catch two buses in the direction of Muda, where he takes his post at 6am, rain or shine. Breakfast in his stomach and dressed in his cleaning management uniform, a company bus brings him more than 10km up to Alto da Boa Vista, where he gets off, prepared with a bucket, shovel, rake, garbage bags, and a Saint George chain around his neck—a gift from his mother to her devout son.

Strangely, the physical cleaning done by the priest is difficult. At 3:30am, when the majority of Rio residents are still sleeping, Alexandre is already on his feet in the municipality of Mesquita, in Baixada Fluminense, leaving his home to catch two buses in the direction of Muda, where he takes his post at 6am, rain or shine. Breakfast in his stomach and dressed in his cleaning management uniform, a company bus brings him more than 10km up to Alto da Boa Vista, where he gets off, prepared with a bucket, shovel, rake, garbage bags, and a Saint George chain around his neck—a gift from his mother to her devout son.

Between one curve and another in Alto, Alexandre takes a few minutes to answer his cell phone, exchange messages, catch his breath, and regain his strength—whether only physical or also spiritual, we can’t be sure—to continue the descent and the cleaning in a routine that repeats from Monday to Saturday and is even more difficult during certain times of the year.

“Monday is always one of the busiest days because the offerings accumulate from the weekend. But on the holy days, like Saint George, the work is even greater. At times, I need help from other city sweepers. There was one Saint Sebastian Day when we had to take away 30 bags of offerings,” he recalls.

It’s enough to just observe the cleaning method of the pai-de-santo city sweeper to know that the lack of reservation towards the peculiar job is not just mere bravado. Without much ceremony, mumbling a few words (the agô, or pardon), he uses the rake to knock down cups and bottles of liquid, break apart and collect the arrangements, fruits, candles, and other offerings in heaping quantities—always with an unworried look—for later pickup by the garbage truck. He still doesn’t show fear when he has to pick up the offerings with his own hands.

The dismantling of the offerings is done without any specific order, except one which makes cleaning most practical. In certain areas with few isolated offerings, the work is fast, not taking longer than five minutes. In other regions, such as Praça do Gato and Curva do S—known as “macumbódromo,” for being a place dedicated to many religious gatherings—up to 30 minutes are spent cleaning due to the quantity, distance between, and the elaborateness of the offerings that must be taken down and collected.

On the grueling walk back to the Comlurb management site in the Muda neighborhood, painful beneath the sun, in the heat, and on rainy days without anywhere to protect himself from rain, all of the offerings, regardless of the type, are taken apart just as naturally by Alexandre. The city sweeper only seems reluctant in front of offerings with recently placed candles (still lit and whole) and those with the remains of dead animals: In the first case, he ignores them and opts to clear them the following day; the second situation demands greater caution, with the use of gloves—“only for hygiene,” he guarantees.

“I leave the most recent offerings for later, out of respect. In addition to the agô (pardon), the only thing that I do is an ebó (a spiritual cleansing) every six months, with my pai-de-santo,” explains the city sweeper.

At 2pm, if there is no delay, he is already back in Mesquita after taking a bus and a train, in time for lunch at home where he lives with his mother, father, one nephew, and his twin sister, and next to one of his brothers—he has three others. The humble abode, located on a dirt street, has signs of still being under construction—Alexandre’s room is being renovated and the backyard contains a stairway with fresh cement—but it is clear to visitors that this is a space for devotees of the deities. To the right of the entrance, in the yard, a kind of cement closet doubles as an alter to his mother’s various religious images.

On the weekends and on his days off, the street cleaner says he likes to “play macumba” in homage to the deities at organized gatherings at friends’ shrines—his, which he recently acquired in Nova Iguaçu, is still being built—and give attention to the 15 filhos-de-santo, or saint-children, he has. One of these shrines just a few blocks from his home can be easily recognized by the clay and porcelain urns above the entrance—called quartinhas.

“Until my shrine is ready, some of the gatherings that I participate in happen here, in a space that belongs to my friend and saint-brother. Some tributes to the deities begin early in the morning and don’t have a set ending time. But they are invigorating,” he says, wearing the traditional priest dress (with orange details just like the street cleaning uniform, something that he says he “didn’t notice before”), as he shows the space built in the middle of the yard of his friends’ home, decorated with paintings, a table for the game of shells (traditional to many African religions), a rug, drums, and other decorations.

Despite his work in Alto da Boa Vista, Alexandre prefers to leave his offerings near where he lives, out of practicality. “I don’t have a car, so it would be a lot of work to bring the things to Alto. There are offerings that are very cumbersome, so it is a lot to carry.”

The priest’s decision to work in Alto wasn’t a coincidence. Before him, the job was done by other cleaners who, out of fear or disrespect, ended up not collecting the fruit, bottles, candles, corn, bowls, wax heads, and other offerings left at the foot of the Tijuca Forest, on Furnas Street. According to Carlos Roberto da Silva, adjunct manager of Comlurb in the region, this has already brought about peculiar incidents:

“We had a guy who would do this type of work, but he was a little disrespectful with the offerings. One day, he was on the side of the street, a car lost control, he doesn’t know how, and hit him. He had his spleen removed, and we sent him to work in another place,” says Carlos Roberto, who’s also initiated in Umbanda. “We had a lot of difficulty replacing him, but then along came Emílio, who agreed to take the position without complaint. He has his own rituals, his own way of doing the work. This is important because when a person is respectful there is no problem, nothing bad happens.”

In charge of a team composed of city sweepers of various religions, including Evangelicals (even priests), Catholics, Spiritualists, and even Atheists, Carlinhos says there is no disrespect between the professionals—“we are like a family”—and sees great value in the exclusive work carried out by Alexandre.

“Here in Alto, it is fundamental to have someone doing this work. There are people leaving offerings 24 hours a day. On some weekends, caravans of people come to hold a spiritual session in the “macumbódromo,” and we have to have someone like Alexandre advising them not to put lit candles near the roots of trees, for example,” the manager explains.

Despite never having met the pai-de-santo city sweeper personally, Luiz Gustavo Trotta, sub-mayor of Grande Tijuca, the area that encompasses Muda and part of Alto da Boa Vista, knows well of Alexandre’s fame. Trotta emphasizes that the city sweeper’s work is essential in allowing the preservation of free religious expression in the area, as established by Brazilian legislation.

“Religious practitioners looking to use the space for their ceremonies is very valid. For this to happen, having a person caring exclusively for this issue, orienting people and looking after the maintenance of the area is very important. And Alexandre demonstrates great professionalism in cleaning up the offerings without any fear,” affirms Trotta.

Already recognized among his professional colleagues and the residents of Muda, Alexandre’s fame soon may be spread throughout Brazil and internationally: the street cleaner was the focus of an article in a French magazine, as well as the starting point and one of the protagonists of a short documentary about religion, tolerance, sectarianism, and prejudice in Rio’s urban spaces.

Produced by Aura Filme, with support from RioFilme, the short film “Gramados e Encruzilhadas” (“Fields and Crossroads”) was finalized this month and will soon begin to circle the country and the world in film festivals.

Produced by Aura Filme, with support from RioFilme, the short film “Gramados e Encruzilhadas” (“Fields and Crossroads”) was finalized this month and will soon begin to circle the country and the world in film festivals.

“Filming took one year, which allowed us to accompany Alexandre while he took away the offerings in Alto on Saint George Day; in the Candomblé shrine; during the ceremony in which he took part as priest; and even on the first day of the year, cleaning the beach after the New Year’s Eve party in Copacabana,” director Valéria Valenzuela recounts. “The biggest challenge was to make a film about people and the manner in which they understand and deal with the world, and not about divergent religious concepts. We did not want to confront beliefs, but rather show different ways of living a religion.”

Recognition aside, however, Alexandre believes that one of his greatest blessings is to be able to work in Alto da Boa Vista.

“It is far, there are days when it is tiring, but I like it here. It is very tranquil. The energy is good,” he affirms, with a light smile on his face.