In 1978 favela residents, liberation theologians and activists mobilized to successfully defend Vidigal against eviction attempts. Those protesting removal used ingenious methods of resistance. These included providing daily coffees to placate COMLURB (Rio’s waste collection company) workers, those employed to evict the protesters, recognizing that they, too, were poor and hungry. These garis (street sweepers) soon made it clear to the government that they wouldn’t remove any of the belongings of residents who wished to stay. Brazilianist Bryan McCann, author of the new book Hard Times in the Marvelous City: From Dictatorship to Democracy in the Favelas of Rio de Janeiro, describes the efforts as “a grassroots movement of humble people emboldened by a noble purpose.”

In 1978 favela residents, liberation theologians and activists mobilized to successfully defend Vidigal against eviction attempts. Those protesting removal used ingenious methods of resistance. These included providing daily coffees to placate COMLURB (Rio’s waste collection company) workers, those employed to evict the protesters, recognizing that they, too, were poor and hungry. These garis (street sweepers) soon made it clear to the government that they wouldn’t remove any of the belongings of residents who wished to stay. Brazilianist Bryan McCann, author of the new book Hard Times in the Marvelous City: From Dictatorship to Democracy in the Favelas of Rio de Janeiro, describes the efforts as “a grassroots movement of humble people emboldened by a noble purpose.”

In the late 1970s and early 1980s residents and governors alike were urgently attempting to break the cycle of rights poverty, believing that the imminent end of the military dictatorship foretold the possibility of a bright future. McCann’s focus at the beginning of the book on the promise of change brings sharp focus to the subsequent failures of the movement to match expectations. What results is a potent description of frustrated hopes, propelling the reader through McCann’s carefully analyzed litany of political disappointments.

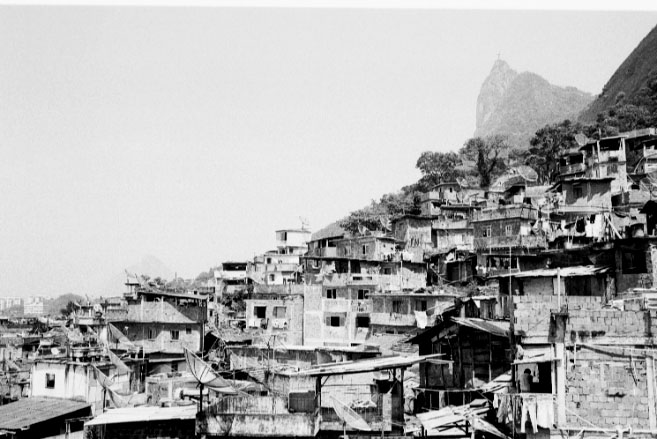

McCann begins at the end of the 1970s when the dream of extension of full and complete citizenship to Rio’s favela residents was very much alive. Activists were seeking to bridge the divide between the favelas and the asphalt (formal city) by challenging longstanding structural and legal problems that consigned residents to difficult lives. In disputing insecure land tenure, limited employment and education, and harassment by the police individuals sought to redemocratize the nation.

Many of those calling for mobilization of favela residents were inspired by Gramscian ideas of occupying spaces. Seemingly unlikely allies, pastoral liberation theologists and Marxists (such as the Unified Black Movement) were pulling in the same direction, seeking to get favela residents into civil society and to then utilize this position to achieve radical ends. Organizations such as FAMERJ (Rio de Janeiro State Federation of Neighborhood Associations) and the Pastoral de Favelas also believed that a new democracy could be created: a democracy that depended on constant, energetic, popular participation. Thus the coalition of the middle class left with favela activists had widespread popular support and looked set to play an important role in the following decades.

In 1982 Socialist candidate Leonel Brizola won the gubernatorial election in the state of Rio largely based on his cultivation of favela support generated through his “socialismo moreno.” This particular brand of socialism stressed racial pride, and emphasized flexibility and redistribution of wealth. His basis of political support was the unorganized urban poor, and he stood for the empowerment (albeit in a paternalistic fashion) of the poorest in society. On election he brought favela leaders into leadership positions in the Democratic Workers Party (PDT), bringing the movement’s grassroots stage to an end.

In 1982 Socialist candidate Leonel Brizola won the gubernatorial election in the state of Rio largely based on his cultivation of favela support generated through his “socialismo moreno.” This particular brand of socialism stressed racial pride, and emphasized flexibility and redistribution of wealth. His basis of political support was the unorganized urban poor, and he stood for the empowerment (albeit in a paternalistic fashion) of the poorest in society. On election he brought favela leaders into leadership positions in the Democratic Workers Party (PDT), bringing the movement’s grassroots stage to an end.

Brizola’s dedication to bridging the gap between rich and poor might have been the beginning of a successful period of urban improvement. He launched a dramatic wave of reforms, not least taking the threat of removal, an ongoing concern, off the table. However, his attempts to revolutionize public education for children, grant land titles to favela residents and demilitarize the police were beset by deep problems. McCann discusses each in depth referencing statistics and individual cases to address specific as well as general reasons for failure.

One example was the program Cada Família Um Lote which was designed to aid the titling process allowing favela residents to file for property regularization through neighborhoods associations. This policy stemmed from Brizola’s belief that the favelas were the solution to a housing crisis, not the problem. Despite having been a priority for residents during the years when eviction was a present threat (particularly when Brazil lived under Military dictatorship), only 2% of the million plots targeted chose to title. Since the threat of evictions had been removed the demands of favela residents had changed to focus on material upgrading and infrastructure development. It wasn’t in the financial or political interest of either residents nor the coordinating neighborhood associations to cooperate, given the threat to the informal rental market and the fear of gentrification posed by titling.

One example was the program Cada Família Um Lote which was designed to aid the titling process allowing favela residents to file for property regularization through neighborhoods associations. This policy stemmed from Brizola’s belief that the favelas were the solution to a housing crisis, not the problem. Despite having been a priority for residents during the years when eviction was a present threat (particularly when Brazil lived under Military dictatorship), only 2% of the million plots targeted chose to title. Since the threat of evictions had been removed the demands of favela residents had changed to focus on material upgrading and infrastructure development. It wasn’t in the financial or political interest of either residents nor the coordinating neighborhood associations to cooperate, given the threat to the informal rental market and the fear of gentrification posed by titling.

The failure of his policing reforms has also been central to Brizola’s legacy. Allegations have continually been made that he ordered Rio’s state police to stay out of favelas. McCann’s exploration of policing during this period shows that this is a myth, borne from difficult circumstances facing Brizola’s regime. The chief of Military Police elected by Brizola, Nazareth Cerquiera, was brought in to implement a new security policy that emphasized community policing in the favelas. One of his aims was to put an end to the polícia pé na porta (“foot in the door police”) custom of policemen entering favela homes without a warrant or permission. However, he didn’t have the strong support in the policing corps he needed to implement these changes.

Whilst Brizola didn’t order troops to stay out of the favelas necessarily, Cerquiera’s attempts to limit punishments of petty crimes (such as for people found playing the roadside gambling game jogo de bicho) and focus on making arrests of higher level criminals was met with distain by officers who’d previously served under the military dictatorship. The subsequent split between newly trained officers and the old guard, accustomed to supplementing their meager incomes with bribes, thus led to a failure to successfully implement the new reforms and an absence of effective policing during this period.

McCann identifies that problems between favela residents and police were further exacerbated by exogenous factors such as the emergence of new drug-trafficking routes in South America and changing patterns of drug consumption: chiefly the growth in cocaine use. As drug traffickers looked to secure bases, they moved to take over Neighborhood Associations, playing on local fear of the police, and paying bribes to association members. McCann argues that drug traffic’s increasing influence in local politics diverted funds away from legitimate projects. Neighborhood Associations that were originally associated with eviction resistance, emboldening residents and communitarian visions became, under Brizola, mediators between individual residents and state agencies. However, the newfound power of these associations meant things often couldn’t get done without the help of a strong ally in the association. The development of cronyism left them susceptible to being manipulated by drug factions. McCann laments, using the example of Santa Marta, that neither effective local leaders nor solid communities could pose obstacles to criminal takeover. The traffickers “chegaram pra valer,” a Carioca expression that translates as “they came to stay,” meaning trafficker infiltration in favela associations spread throughout the entire city, hijacking and distorting the communitarian mobilization that had once given these favelas so much hope.

Hard Times clearly demonstrates how the aspirations of the 1980s were slowly broken down by small factors, those found in what he describes as the interstices or crucial, small details. His descriptions of Braga’s rule, the development of CIEP schools designed by Niemeyer displaying fervent commitment to radical educational reform, and the growth of the NGO sector and more provide a comprehensive overview of a crucial period in Rio de Janeiro’s history and a valuable source of critical history.

Hard Times ends on a positive note. His follow up interviews with Neighborhood Associations from 2010-2013 led him to conclude that much has been retained from the period, and that positive change is finally achievable. In his discussion of the Pacifying Police Units (UPPs) he highlights that Nazareth Cerquiera’s vision of crime prevention and community policing was finally being, in part, realized. McCann does however acknowledge that a century of violent policing is not easily overturned. He also sees the recent wave of protests as a sign of progress. The vigorous debates over public spending on the Olympics, displacement and security, all demonstrate that favela residents are directly participating politically to define the future of the city.

McCann concludes that “the current moment offers the opportunity, for the first time in 30 years, of asserting positive difference whilst combating exclusion from the rule of law.” If the lessons of the 1980s are learned–prioritizing stable frameworks for gradual improvement over radical, poorly implemented, reform–there is an opportunity to empower and provide a bright future for Rio’s favela residents.