This is Part 2 in a four-part series on the History of Rio de Janeiro’s Military Police. Click for Parts 1, 3, and 4.

Bandido favelado

não se varre com vassoura

se varre com granada

com fuzil, metralhadora(Favela criminal

you don’t sweep them away with a broom

you sweep them away with grenades

with rifles, machine guns)

As we have seen, the mandate of the Brazilian police force throughout its history has been heavily based on colonial notions of citizenship. Those ‘with’ tend to be seen as honest, hardworking citizens, whilst those ‘without’ are viewed as criminals, or potential criminals. In the last 50 years the Military Police has increasingly used lethal force in poorer parts of the city, employing an “act first and ask questions later” mentality.

During the military dictatorship which lasted between 1964 and 1985, the police were charged with confronting the internal enemy, political opponents of the regime. It was during this period that the police took on a profoundly military role: any suggestion that their objective was to protect and defend the public now disappeared. National security, anti-guerrilla and riot control tactics were the principal aspects of police training under the military regime. This national security doctrine was used to motivate, justify and defend the numerous atrocities which took place over the course of these two decades. Torture and killing were widespread, and impunity almost guaranteed. Death squads such as the Scuderie Detetive Le Cocq led by the Homens de Ouro consisted of police officers who carried out private justice for local businesspeople, principally in the favelas. These groups were the antecedents of the militias of recent years.

During the military dictatorship which lasted between 1964 and 1985, the police were charged with confronting the internal enemy, political opponents of the regime. It was during this period that the police took on a profoundly military role: any suggestion that their objective was to protect and defend the public now disappeared. National security, anti-guerrilla and riot control tactics were the principal aspects of police training under the military regime. This national security doctrine was used to motivate, justify and defend the numerous atrocities which took place over the course of these two decades. Torture and killing were widespread, and impunity almost guaranteed. Death squads such as the Scuderie Detetive Le Cocq led by the Homens de Ouro consisted of police officers who carried out private justice for local businesspeople, principally in the favelas. These groups were the antecedents of the militias of recent years.

With the fall of the dictatorship, it was hoped that the violence which marked that era would decrease. However, paradoxically, the following 25 years were some of the most brutal in Brazil´s history. Between 1991 and 2007 there was an average of 6,826 homicides per year in the state of Rio de Janeiro alone, figures comparable with urban areas of countries in civil war. In 2002 records showed that there were 62 homicides per 100,000 people in Rio, a statistic similar to that of Yugoslavia in the 1990s or Iraq during the last decade. In 2005, 3% of the world´s population lived in Brazil, yet 11% of its homicides happened there.

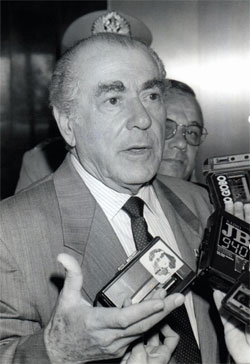

Much of this surge in violence was down to the new dynamic which existed between the state and the favela from the eighties onwards. Firstly, the governor of Rio de Janeiro, Leonel Brizola of the PDT (Partido Democrático Trabalhista) decided to implement a shift of policy. Having been exiled during the dictatorship and having suffered at the hands of the police, he concluded that the massive police operations which threatened and intimidated many favela communities during the military regime needed to stop. At around the same time, organized gangs in the favelas were realizing there were huge amounts of money to be made in the drug trade. Groups such as Comando Vermelho and Amigos dos Amigos took control of many communities, beginning to oversee access to gas, water, digital television, dominating the social scene of the favela, and in many cases imparting (their own style of) justice within the communities. Some have blamed Brizola for allowing drug trafficking to flourish in the favelas, yet realistically the perfect conditions made its growth inevitable. However, Brizola is not entirely devoid of blame: his hands-off policy with regard to favela communities further stretched the breach between the state and the favela communities, and made policing this territory much more difficult.

Much of this surge in violence was down to the new dynamic which existed between the state and the favela from the eighties onwards. Firstly, the governor of Rio de Janeiro, Leonel Brizola of the PDT (Partido Democrático Trabalhista) decided to implement a shift of policy. Having been exiled during the dictatorship and having suffered at the hands of the police, he concluded that the massive police operations which threatened and intimidated many favela communities during the military regime needed to stop. At around the same time, organized gangs in the favelas were realizing there were huge amounts of money to be made in the drug trade. Groups such as Comando Vermelho and Amigos dos Amigos took control of many communities, beginning to oversee access to gas, water, digital television, dominating the social scene of the favela, and in many cases imparting (their own style of) justice within the communities. Some have blamed Brizola for allowing drug trafficking to flourish in the favelas, yet realistically the perfect conditions made its growth inevitable. However, Brizola is not entirely devoid of blame: his hands-off policy with regard to favela communities further stretched the breach between the state and the favela communities, and made policing this territory much more difficult.

It was in this context of the growth of the drug trade that the police (and the outside world, the media, and cinema) began to intrinsically relate inhabitants of the favela with criminality. No matter that only a small percentage of the people in these communities were involved in crime; the media and the state themselves promoted and encouraged this image. This created a fear of the favela as a space and consequently a fear of its inhabitants, leading the city to be divided into two spaces in the public imagination: a favela and o asfalto (the ‘favela’ and the ‘asphalt,’ or formal city). So when the police began to make violent incursions into favelas under the premise of fighting a drug war, these actions were widely supported. Comments such as “a good criminal is a dead criminal” became commonplace, and the Military Police was even described as “the best social insecticide” by one if its highest ranking officers. Many of those who lived in the asphalt of the city felt safer knowing that the police were taking strong action against criminals, supporting the ´by any means necessary´ philosophy.

It was in this context of the growth of the drug trade that the police (and the outside world, the media, and cinema) began to intrinsically relate inhabitants of the favela with criminality. No matter that only a small percentage of the people in these communities were involved in crime; the media and the state themselves promoted and encouraged this image. This created a fear of the favela as a space and consequently a fear of its inhabitants, leading the city to be divided into two spaces in the public imagination: a favela and o asfalto (the ‘favela’ and the ‘asphalt,’ or formal city). So when the police began to make violent incursions into favelas under the premise of fighting a drug war, these actions were widely supported. Comments such as “a good criminal is a dead criminal” became commonplace, and the Military Police was even described as “the best social insecticide” by one if its highest ranking officers. Many of those who lived in the asphalt of the city felt safer knowing that the police were taking strong action against criminals, supporting the ´by any means necessary´ philosophy.

In 1998 Human Rights Watch reported that Rio´s Military Police were killing 20 people per month, and blamed the chief of police at the time, Nelson Cerqueira, for rewarding officers involved for their “acts of bravery.” Police violence reached a peak in 2007, when Rio´s forces killed 1,330 people, the large majority of these in the poorest parts of the city. All these deaths were registered as autos de resistência, the term used to describe a confrontation whereby the police responded in self defense. However, HRW discovered that many of these cases were inconsistent with acts of self defense: bullets in the back of the head, multiple (in one case 32) gunshot wounds.

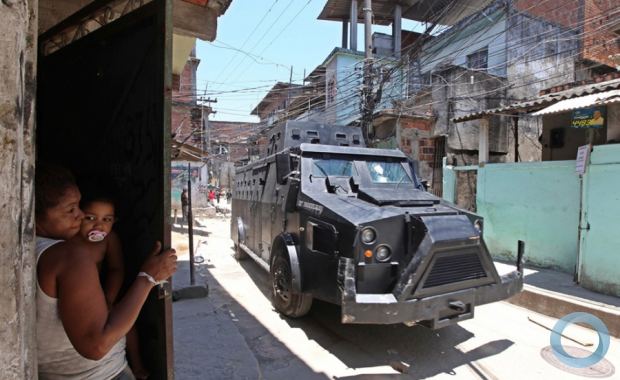

Most of this lethal violence was carried out by the elite arm of the Military Police, the BOPE. With a badge consisting of two pistols in front of a skull skewered by a knife, BOPE´s mandate is fairly clear. That the song quoted above was used in BOPE training sessions is a good indication of how the state wanted its officers to treat the problems in the favelas. Police would enter the favelas in scenes now made famous by films such as Elite Squad with rapid, focused attacks using military grade weapons. The caveirão—a large armored truck which enters the favela during police raids–became a symbol of how the police viewed the inhabitants of the favela. Its presence brings fear and intimidation to these communities, implicating all its residents as potential criminals. After these raids the police would return to the safety of the asfalto, making it even clearer that the favela was a space excluded from the city. Practically the only police presence in some favelas has come in the form of these raids, so it was no surprise that these communities´ relationships with the police were extremely hostile.

Most of this lethal violence was carried out by the elite arm of the Military Police, the BOPE. With a badge consisting of two pistols in front of a skull skewered by a knife, BOPE´s mandate is fairly clear. That the song quoted above was used in BOPE training sessions is a good indication of how the state wanted its officers to treat the problems in the favelas. Police would enter the favelas in scenes now made famous by films such as Elite Squad with rapid, focused attacks using military grade weapons. The caveirão—a large armored truck which enters the favela during police raids–became a symbol of how the police viewed the inhabitants of the favela. Its presence brings fear and intimidation to these communities, implicating all its residents as potential criminals. After these raids the police would return to the safety of the asfalto, making it even clearer that the favela was a space excluded from the city. Practically the only police presence in some favelas has come in the form of these raids, so it was no surprise that these communities´ relationships with the police were extremely hostile.

Between the end of the military dictatorship (in 1985) and 2008 therefore, the Military Police had become a large part of the public security problem in Rio. The legacy of the military regime had transformed the Military Police into a force trained in a war-like model of policing, with rule of law and citizen rights largely ignored. By 2008, the Military Police in Rio were killing one person for every 23 arrested, a statistic which is shocking when put into context: in the USA this ratio is 1:37,000. A change in public security policy in the favelas was needed, and community policing was experimented in various forms before the Pacifying Police Units (UPPs) were finally launched in December 2008.

This is Part 2 in a four-part series on the History of Rio de Janeiro’s Military Police. Click for Parts 1, 3, and 4.

Patrick Ashcroft is a researcher currently based in Rio de Janeiro. His thesis on Rio’s Pacifying Police Units (UPPs) was completed as part of a Master’s degree in Contemporary History from the University of Santiago de Compostela, Spain.