On Saturday, March 22, Vila Autódromo experienced what witnesses refer to as the City’s “divide and conquer” strategy: coercive tactics designed to create discord in the community. An injunction filed by the Public Defender’s office was approved by Chief Judge Tereza de Andrade Castro Neves on Friday, March 21, stopping demolitions in the community until the City’s plans for the area have been presented. On Saturday, City officials including Tiago Mohamed, the sub-mayor of Barra da Tijuca, visited Vila Autódromo to inform the seven families prepared to leave for Parque Carioca apartments that day that they could not receive the new apartments, falsely using the injunction as the reason. The confusion led to conflict between residents with several of them closing the Embaixador Abelardo Bueno Avenue.

On Saturday, March 22, Vila Autódromo experienced what witnesses refer to as the City’s “divide and conquer” strategy: coercive tactics designed to create discord in the community. An injunction filed by the Public Defender’s office was approved by Chief Judge Tereza de Andrade Castro Neves on Friday, March 21, stopping demolitions in the community until the City’s plans for the area have been presented. On Saturday, City officials including Tiago Mohamed, the sub-mayor of Barra da Tijuca, visited Vila Autódromo to inform the seven families prepared to leave for Parque Carioca apartments that day that they could not receive the new apartments, falsely using the injunction as the reason. The confusion led to conflict between residents with several of them closing the Embaixador Abelardo Bueno Avenue.

These latest events come during a moment of tension and transition for the community of Vila Autódromo, as the first housing demolitions took place this month with decisive force and speed. Families who are committed to staying are holding weekly meetings to strengthen unity and resistance efforts. Those who have opted for resettlement housing through the Minha Casa Minha Vida (MCMV) program are expecting to be moved to Parque Carioca in the coming weeks. Yet several other families agreed to leave after receiving considerable financial compensation for their homes following negotiations.

These latest events come during a moment of tension and transition for the community of Vila Autódromo, as the first housing demolitions took place this month with decisive force and speed. Families who are committed to staying are holding weekly meetings to strengthen unity and resistance efforts. Those who have opted for resettlement housing through the Minha Casa Minha Vida (MCMV) program are expecting to be moved to Parque Carioca in the coming weeks. Yet several other families agreed to leave after receiving considerable financial compensation for their homes following negotiations.

Activists and community leaders allege these demolitions undermine the community’s 99-year lease to the land, resistance efforts and collective negotiation strategies. Those committed to staying, as is their right, fear the empty lots from the demolished properties of neighbors who have left will make remaining unbearable, by imposing psychological pressure on families in adjacent houses concerned about the structural integrity of their homes or potential health problems caused by debris from demolitions.

The first families to sign contracts for the Parque Carioca housing–located just one kilometer from Vila Autódromo thanks to early resistance efforts–are expected to be relocated in the coming weeks. But some initially intending to move have changed their mind after learning of contractual clauses forbidding them to sell or rent the new apartment for ten years, despite having been told earlier, in a meeting with the Mayor, they would be permitted to sell on arrival.

Meanwhile, the Deutsche Bank Urban Age Award–won in late 2013 for efforts to “improve the physical conditions of their community and the lives of its residents”–is displayed in the Neighborhood Association, and plans are underway for the construction of the new community day care center using the US$80,000 prize money. As some families prepare to leave, this project stands as a powerful symbol of Vila Autódromo’s commitment to stay. The community had been holding weekly events to raise funds to build this day care center, put on hold in 2009 when the Mayor announced the community would be removed, and the Association had to channel all energies towards countering eviction.

Ongoing Pressure

The community of Vila Autódromo was settled 40 years ago by fisherman on the Jacarepaguá lagoon, in the West Zone of Rio de Janeiro, an area now characterized by rampant real estate speculation and condominium construction. Located along the edge of the 2016 Olympic Park, Vila Autódromo has been threatened with repeated eviction attempts over the last 20 years, and the pretext for its removal has changed numerous times. The City’s current proposal would remove 280 out of 583 families for new access roads to the Olympic site and for proximity to the lagoon.

The community of Vila Autódromo was settled 40 years ago by fisherman on the Jacarepaguá lagoon, in the West Zone of Rio de Janeiro, an area now characterized by rampant real estate speculation and condominium construction. Located along the edge of the 2016 Olympic Park, Vila Autódromo has been threatened with repeated eviction attempts over the last 20 years, and the pretext for its removal has changed numerous times. The City’s current proposal would remove 280 out of 583 families for new access roads to the Olympic site and for proximity to the lagoon.

In August 2013, Mayor Eduardo Paes announced that those who do not want to leave can opt for resettlement within the community. On Wednesday, March 19, he reiterated that the City was not forcing any families to leave Vila Autódromo: “There is not a single eviction in Vila Autódromo. No one is leaving without wanting to… For the people who want to leave, I will give them an apartment.”

However, Altair Guimarães, Neighborhood Association President, told Agência Estado that there is still “pressure from all sides, but various families have not agreed to negotiate.” He reiterated that the community has a legal title and that, ultimately, “what justifies this is real estate speculation.”

Community Organizing and Resistance

The 100 families determined to remain in Vila Autódromo are holding weekly meetings at the Neighborhood Association to strengthen their resistance efforts, exchange information, and prepare for the upcoming wave of housing demolitions. At one meeting, André Constantine, resident of Babilônia favela in Rio’s South Zone and an activist from the Favela Não Se Cala movement, called for the solidarity of favela residents struggling against removals across the city. “Our house is not just bricks, tiles and walls,” he said. “Our house is our history, our memory, and when they take it away, they are taking part of our lives and our dignity.”

At the meeting, activists and community leaders called for unity, reminding residents of their legal right to remain, and warning them of the City’s tactics to pressure families into signing away their homes. Some explained that in other communities that were removed, city officials arrived with falsified documents granting permission to demolish homes. Other examples of “blackmail” appear to be currently playing out in the community, such as telling families they won’t give them keys to the resettlement apartment until the City has demolished their old home, thereby creating internal divisions when the judge ordered a stop to demolitions.

Residents demand the details of the City’s plans–specifying the exact number of families in the trajectory of works and the urbanization plans for those who will remain– be made publicly available to the community before demolitions continue. Furthermore, the City has refused to discuss an updated People’s Plan for the works, which was designed by the community working with city planners from the two local federal universities, to minimize the number of evictions. They emphasized that, as per the mayor’s word, families located in the trajectory of new roads to the Olympic site be resettled within the community.

Residents demand the details of the City’s plans–specifying the exact number of families in the trajectory of works and the urbanization plans for those who will remain– be made publicly available to the community before demolitions continue. Furthermore, the City has refused to discuss an updated People’s Plan for the works, which was designed by the community working with city planners from the two local federal universities, to minimize the number of evictions. They emphasized that, as per the mayor’s word, families located in the trajectory of new roads to the Olympic site be resettled within the community.

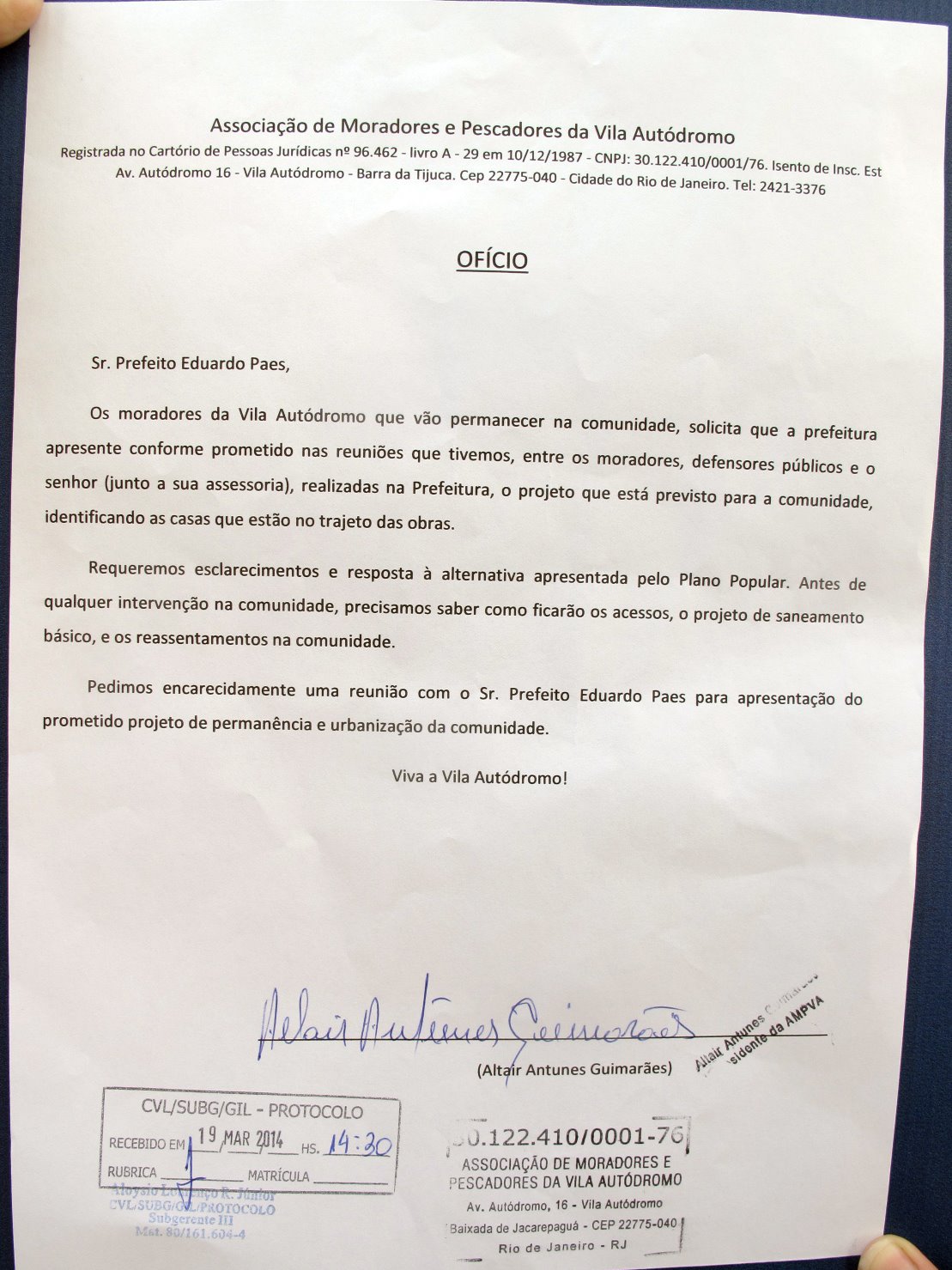

Residents drafted a letter to Mayor Eduardo Paes, which was presented on Wednesday, March 19, demanding the release of the plans for the new proposed roads. Without this information, they caution that the City may overestimate the number of families required to relocate. The letter read:

The residents of Vila Autodromo who will remain in the community call upon the City to present–as was promised in a meeting held at City Hall with residents, public defenders, and the Mayor himself–the project that is planned for the community, identifying the houses in the trajectory of the works.

We demand clarification and response to the alternative presented by the People’s Plan. Prior to any intervention in the community, we need to know how the access, the proposals for basic sanitation, and resettlement in the community will be [afterwards].

As some families prepare to leave, others–in an act of civil disobedience–continue to build up and work on their houses. A group of neighbors working on a construction project state with absolute certainty that they are not leaving. One of them, José, a resident of six years, says he and others feel “cheated” by the mayor. Despite the mayor’s assurances at the meeting in Rio Centro that the apartment would be theirs outright–to occupy or sell as they please–they have discovered contractual clauses that prohibit them from selling or renting out the apartment for the next ten years. As a result, many families who were prepared to accept the Parque Carioca housing are now reconsidering.

Leaving for Parque Carioca

Reportedly over 200 families have already signed the Minha Casa Minha Vida contract to accept the Parque Carioca housing. One such resident, Regina, sits with her sister a few houses down from the first demolition. “My husband and I built this home with great difficulty,” she says, “my whole life struggling to improve this house and raise my family. But now I am tired, I cannot bear this anymore.”

Regina expressed conflicting emotions about the upcoming move after living in the community for 30 years. She was excited to receive the new first floor apartment, which will be accessible for her disabled son, and feels fortunate to have received an apartment in such close proximity, unlike so many communities in which residents were relocated to peripheral areas. She believes the mayor’s promises about its condition will be fulfilled: residents have been told to expect a furnished apartment (fridge, stove, bed, with option for 2-3 bedrooms), a community pool, leisure area, and commercial space in the condominium complex.

Regina was nostalgic and sad to leave her house along the lagoon that is full of memories: the children and grandchildren she had raised there, the Japanese plants cultivated by her deceased mother, and the bedroom of her son, left intact since he was murdered by drug traffickers several years ago.

Although she is pleased at the prospect of the relocation housing, Regina also appeared tired of the insecurity and stress that accompany resistance: “I have already been here 30 years in this life of stay or go, stay or go… So I chose the [Parque Carioca] apartment because I don’t have the health to build a new house, to keep resisting […] My heart is heavy, but what are we going to do? Keep living in this way, not knowing if we will have a future or not?” Her neighbors on both sides have passed away, one of whom had a heart attack Regina believes was brought on by the emotional stress related to this removal process.

Another resident Carmelia, initially resisted the proposed evictions and regularly participated in community organizing meetings. Although she was skeptical of the government’s intentions–suspecting a “scam” on their part–she has since changed her mind and decided to accept an apartment in the Parque Carioca development, with high hopes of what it will bring.

“I am happy, because I am going to something that is mine,” she says. “[This is] despite the fact that it is an apartment, not something I always wanted.” She is looking forward to the move, confident that it will bring certain conveniences, such as closer proximity to her husband’s work and daughter’s school, and better transport options for her son who studies in Centro.

Yet Carmelia acknowledges that she made various compromises when she accepted the new housing. She never wanted to live in an apartment and intends to sell it as soon as possible. Despite the misinformation regarding the Minha Casa Minha Vida contract, Carmelia has come to terms with the fact that she must live there for a full decade.

Carmelia has spoken with municipal representatives about using her house–which is located in the center of Vila Autódromo–to resettle those residents whose homes will be demolished for the road construction but do not want to leave the community.

She is leaving Vila Autódromo for the Parque Carioca apartment with a number of mixed emotions: excitement and hope, conflicting with apprehension and uncertainty. “It’s a shot in the dark,” she reflects. “I don’t know if I’ll hit the target.”

In this moment of uncertainty, some families are preparing to leave for Parque Carioca apartments and others stand firm in their determination to remain in their homes and community. These families are strengthening their resistence efforts–including legal action–in the face of divisive tactics by the City. Saturday’s tensions and altercations highlight the frustration and stress that the ongoing removal process has imposed upon residents.