On Tuesday, April 22, a young man was found dead inside a day care center in Pavão-Pavãozinho, South Zone of Rio, allegedly killed by local Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) officers. His body, curled up on the floor, reportedly bore boot marks and other signs of beating. A later photo appeared to show that he had also been shot in the back. The victim, Douglas Rafael da Silva Pereira (known as DG), was a dancer on Rede Globo’s hugely popular Sunday afternoon TV program, Esquenta.

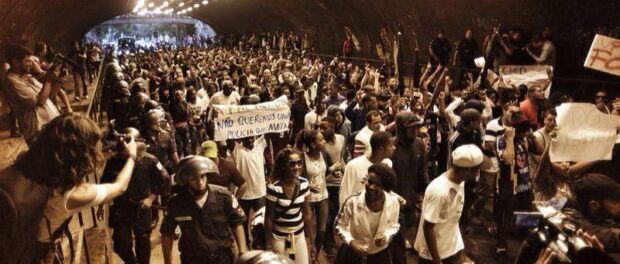

The reaction to DG’s death was explosive, with subsequent protests–spilling out into Copacabana, to the shock of tourists and Rio’s wealthy–receiving extensive international coverage. The parallels to Amarildo Dias de Souza’s torture and death at the hands of UPP police in Rocinha last July, a major blow to the reputation of the pacification program, has reignited fierce debate within Brazil about the nature of the UPPs, militarized policing, and their relation to favela residents. Controversy has escalated in recent months, and for many, this has been the tipping point. One resident of Pavão-Pavãozinho asked: “How are we supposed to accept this project here continuing in the name of pacification? When, truthfully, they are entering prepared for a war, a war against people who are tired from a history of war and fighting. They are entering and bringing yet more war.”

The reaction to DG’s death was explosive, with subsequent protests–spilling out into Copacabana, to the shock of tourists and Rio’s wealthy–receiving extensive international coverage. The parallels to Amarildo Dias de Souza’s torture and death at the hands of UPP police in Rocinha last July, a major blow to the reputation of the pacification program, has reignited fierce debate within Brazil about the nature of the UPPs, militarized policing, and their relation to favela residents. Controversy has escalated in recent months, and for many, this has been the tipping point. One resident of Pavão-Pavãozinho asked: “How are we supposed to accept this project here continuing in the name of pacification? When, truthfully, they are entering prepared for a war, a war against people who are tired from a history of war and fighting. They are entering and bringing yet more war.”

DG’s death might have gone largely un-discussed in mainstream media were it not for his public visibility on Esquenta. The death of one of their own has prompted the Globo Corporation to rally around DG and his family, with O Globo even breaking its usual line by running a piece suggesting that UPPs are in a “moment of crisis.” On the edition of Esquenta following DG’s death, the emotional presenter Regina Casé received DG’s family and friends to discuss his tragic death, yet the discussion was largely sanitized, initially with minimal reference to the context of DG’s death–UPPs, the criminalization of poverty, the history of police violence, or favelas–until the silence became unsustainable.

DG’s death might have gone largely un-discussed in mainstream media were it not for his public visibility on Esquenta. The death of one of their own has prompted the Globo Corporation to rally around DG and his family, with O Globo even breaking its usual line by running a piece suggesting that UPPs are in a “moment of crisis.” On the edition of Esquenta following DG’s death, the emotional presenter Regina Casé received DG’s family and friends to discuss his tragic death, yet the discussion was largely sanitized, initially with minimal reference to the context of DG’s death–UPPs, the criminalization of poverty, the history of police violence, or favelas–until the silence became unsustainable.

In a poignant moment, Casé turned to the audience: “Who here is called Silva?” she asked. After a significant number put their hands up, she lamented that “Douglas was just another Silva,” a reference to the funk song about the anonymity of those who die in the periferias of Brazil, where many bear this name. And in an even more unquieting moment, she asked how many people in the audience had lost a loved one, friend or neighbor to gun violence, and dozens of hands shot up.

DG’s visibility helped ensure his death not go unnoticed, and that he was not “just another Silva.” Yet on the very same day, in the protests following DG’s death, resident of Pavão-Pavãozinho and another Silva–literally–was killed. Edilson da Silva dos Santos (known as Mateuzinho), was shot in the head and died soon after, his death not receiving nearly the same attention. The 27 year-old reportedly had mental problems, and his burial, the day before Esquenta, was attended by only 21 people–there was not even a chapel service.

DG’s visibility helped ensure his death not go unnoticed, and that he was not “just another Silva.” Yet on the very same day, in the protests following DG’s death, resident of Pavão-Pavãozinho and another Silva–literally–was killed. Edilson da Silva dos Santos (known as Mateuzinho), was shot in the head and died soon after, his death not receiving nearly the same attention. The 27 year-old reportedly had mental problems, and his burial, the day before Esquenta, was attended by only 21 people–there was not even a chapel service.

Deaths and attacks have continued around the city since DG and Mateuzinho died. On Sunday April 27, the day of Esquenta, 71 year-old Dona Dalva, full name Arlinda Bezerra das Chagas, was caught up in a shootout and killed in the Complexo do Alemão, North Zone, far away from the spotlight of Copacabana. Even further north, in Morro do Chapadão, Costa Barros, 17 year-old Luiz Alberto Cunha was killed in a shootout the next day.

Despite muted reactions in the mainstream media, these deaths sparked fury from the communities, with nine buses burned down in subsequent protests as violence continued to spiral. Shockingly, a 12 year-old boy was shot in Pavão-Pavãozinho on the same night that DG and Mateuzinho were killed.

In Alemão, in protests following Dona Dalva’s death, a UPA health center was the scene of rioting when a young shop assistant, Carlos Alberto de Souza, was shot in the stomach and taken there: “The family desperately asked for information and the police did not answer. Fearing that Carlos was being tortured or even executed, the masses attacked the UPA… Carlos was left agonizing without medical attention for at least two hours.” Rio Mayor Eduardo Paes and new State Governor Luiz Fernando Pezão visited the scene the following day, denouncing the “delinquents” who had attacked the unit, labeling them criminals who interfere with the pacification.

In Alemão, in protests following Dona Dalva’s death, a UPA health center was the scene of rioting when a young shop assistant, Carlos Alberto de Souza, was shot in the stomach and taken there: “The family desperately asked for information and the police did not answer. Fearing that Carlos was being tortured or even executed, the masses attacked the UPA… Carlos was left agonizing without medical attention for at least two hours.” Rio Mayor Eduardo Paes and new State Governor Luiz Fernando Pezão visited the scene the following day, denouncing the “delinquents” who had attacked the unit, labeling them criminals who interfere with the pacification.

The extent of the damage done to the reputation of the UPPs, and subsequent attempts to limit it, was evidenced in an article published by O Globo, before being quickly and surreptitiously taken off the site: “Military Police request that journalists do not accompany the operation in Alemão.” The strategy of controlling press reports on the extent of the violence taking place there was quickly denounced. One human rights lawyer posted the article with the comment: “the Military Police does not want witnesses to the violations committed by its representatives, the excesses in approaching [residents], the absolute psychological lack of control in [their] war machine.” A community journalist reported that journalists in Alemão were under considerable risk: “Independent journalists almost died yesterday during the protests, and today O Globo took this article, published yesterday, off the air.”

The murder of a public figure such as DG led to a crisis of public opinion on the UPPs–one that has been brewing over the past year but largely brushed aside by public officials and a complacent media. However, as cracks in the program grow deeper, becoming harder to hide, the complaints coming from within–that the militarized presence of the state in favelas today is in many places no different from that of the past, and that abuse and repression are happening despite the marketing of “pacification” and “bringing security to the people who live there”–appear to be ever more present in mainstream debate.

The public mourning of DG, with international repercussions, has helped foster this debate. However, as other “Silvas” continue to be killed, quickly swallowed up by the anonymity of statistics, there is still a considerable distance to be travelled, and it is necessary to strengthen and democratize the channels of communication coming out of the favelas. Only in this way can the experience of favela residents in relation to the UPPs be freely expressed and scrutinized, breaking the pattern of silence with one or two occasionally slipping through the net–as happened with Amarildo and now DG.