Last weekend, Columbia University’s Studio X – Carioca Center of Design hosted Entremeios, a series of conferences about lifestyles and creative practices in the city, inviting speakers from the fields of design, architecture, urbanism, anthropology and other social sciences. The organizers insisted on design as a powerful mediator, both open and dangerous.

Some of the talks were focused on the local scale, namely the center of Rio de Janeiro. Others came from afar to discuss urban activism or the interaction between design and anthropology in the Nordic countries of Europe. Many of the topics discussed, whether about grassroots placemaking activities or about the power relations intrinsic to the creation of the city, are relevant to Rio’s favelas.

Wendy Gunn, professor of Design Anthropology, said that the difference between the Scandinavian context and Brazil is that here things are “not all sewn up”, so there is potential for things that would not be possible in Denmark.

Planners and other urban actors can indeed learn from the vernacular nature of favelas: spaces evolve according to users’ needs and allow for everyday fun and spontaneous activities. As opposed to planned housing, favelas do not have rigid objectives, timelines and rules, thus providing affordable housing that is never finished, but rather always being built by and for the community.

This collaborative and evolving design of favelas is also sustainable in the environmental sense, fostering a mixed-use urban composition and a pedestrian-oriented configuration: favela residents rely less on cars and more on bikes and their two feet to get around. They are often situated on Rio’s hills, offering great views of the ocean and forest, but also constitute an attraction in themselves, echoing the aesthetics of historic Portuguese cities or the Greek postcard landscapes.

Their urban informality encourages sociability and community: the close-knit relationships of the favela contrast with the anonymity of neighbors in condominiums.

One of the weekend’s presentations highlighted the role of favelas as cultural incubators through the Nós com todos: não tem como não dançar (Us with everyone: It’s hard not to dance) film. The Nós com Todos project aims to improve conviviality between the neighboring–but historically rival–communities of Borel and Casa Branca, through funk, hip-hop, b-boy and passinho, expressions of favela culture, ever-present in the streets, alleys and other public spaces of Rio’s communities.

Urban interventions in the favelas should take into account these qualities, both of the physical and social environments. Eeva Berglund, anthropology scholar, reflected on the weekend by lauding the Brazilian culture and skill of “making do”: using common sense and what is at hand, repurposing objects… Despite media portrayals of favelas as scenes of violence and misery, they can just as easily be seen as places of creativity and abundance. In many favelas, art and design meet sustainability, for instance with Alex Sandro’s glass recycling initiative.

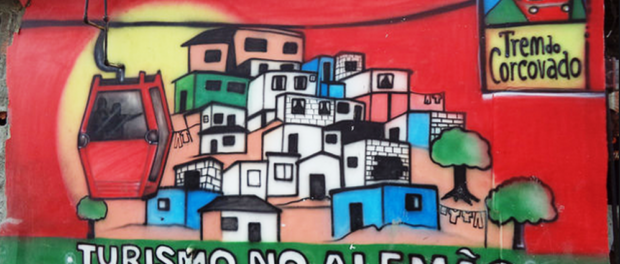

The do-it-yourself mentality extends to the favela’s urban fabric, for instance with the project aiming to foster a collective vision for Alemão’s public spaces through an interactive exhibition.

Marcos Rosa, author of Handmade Urbanism: From Community Initiatives to Participatory Models gave a talk about mapping “lighter, quicker, cheaper” ways of creating the city. He insists that the mainstream conception of how cities are made–as technical interventions from the State–is wrong. Cities are indeed complex, porous constructions that involve the participation of many people.

State-implemented infrastructure can also be adapted to use and humanized. For instance, the incremental urbanism in Cidade de Deus.

Anthropologist Mariana Cavalcanti started her talk, on the aesthetics of State intervention in the landscape, by saying that favelas are part of the “margins” on at least two accounts. They are in the global South and they are sometimes situated at the periphery of the city, places where the State intervenes in a different way, which is often complicated and questionable.

Her research is about the construction process of favelas, which often start as temporary wooden houses but evolve to an urban settlement that is way more than what the word “slum” characterizes. For example, this seemingly rural photo from 1960 is now a dynamic hub within the community of Borel; Rio de Janeiro’s favelas can indeed change rapidly and Cavalcanti has looked into the impact of the State on their development:

For decades, the favela was where the city stopped: the State did not provide any services, such as waste collection or water, never mind interventions in the built environment. Therefore favela residents got together and worked collectively to improve their communities, through what is called mutirão, a Tupi word used to describe group work, or collective action, with benefits for all. In the 1980s this hard work was remunerated for the first time by the municipal Projeto Mutirão program.

Favela-Bairro however is probably a more significant program of favela upgrading in Rio de Janeiro. Primarily concerned with infrastructure improvements, it also included the idea of providing public social services, such as day care facilities, in some of the favelas served. Favela-Bairro’s aim was not focused on remaking the city and its image, but rather on improving the organization of spaces within the favelas, which is different from programs directed towards favelas today.

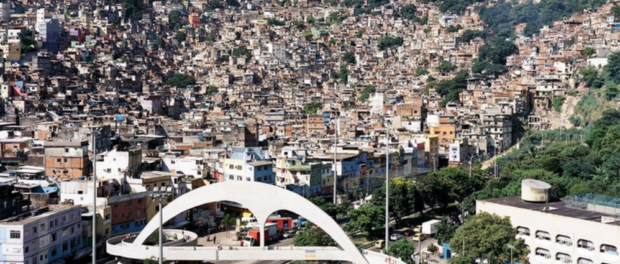

Take for instance the bridge designed by Niemeyer at the entrance of Rocinha, a project of the federal Growth Acceleration Program (PAC): it can be seen from afar, it can be read in the landscape. Cavalcanti affirms that the legacy of the PAC is the inscription of the favela into the cityscape; however it is not really the favela, but rather a bridge, a gateway: what can be seen from afar is the connection, the integration, “the arrival of the State.”

The huge Cantagalo elevator and the Alemão cable cars are similar symbols, connecting the favela to the formal city.

Cavalcanti says that it is subtle but eloquent that tourists arriving from Rio’s international airport are protected from the sight of Complexo da Maré by a “soundwall,” while the view of the cable car visibly dominates the Complexo do Alemão. By the same logic, the Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) buildings are very evident in Rio’s favelas.

Rocinha’s residents ask for basic sanitation, but that would not be as obvious in the landscape as a cable car project. Some favela residents shine a spotlight on this strategy by making deaths linked to police violence visible with signs above roadways, or, in other cases, filing law suits against the State. The State literally makes its mark on the favelas through the signs on the houses to be demolished and the ruins left by the ongoing evictions which began anew in 2010 after Rio was announced to host the 2016 Olympic Games.

Cavalcanti says that the simple dichotomy between favela and “asphalt” (formal city) does not communicate all the inequalities at the regional–Rio Metropolitan–level: for instance in the industrial outskirts where manufacturing spaces are recreated as Growth Acceleration Program (PAC) or Minha Casa, Minha Vida public housing projects.

The newly created leisure areas in Manguinhos echo the central plazas of Spanish colonial cities: an oasis from which everything radiates. Cavalcanti observed that among this urbanismo redentor (“redeeming urbanism”) of public services and constructions, drug traffickers and cracolândias (cracklands) reappear on the concreto novinho (“brand new concrete”). She reminded us that urban planning is complex, has mixed results and that many things escape from the implementation of projects.

The construction of the Minha Casa Minha Vida “Barrio Carioca” public housing project in Triagem, North Zone, is of a huge scale and is intended to house people removed from “at-risk” areas. The region is transformed by this urbanism: it raises questions about territory and poverty. Cavalcanti says it is easy to compare Cantagalo favela and its neighbor, formal upscale Ipanema, but that Triagem’s new mass public housing needs an ethnographic study to be built from the bottom up. There is no sociology existing about it.

The destruction of favelas leaves ruins behind; hundreds of families occupy abandoned factories and only some are then removed to social housing. Cavalcanti asserts that we can see the relations of humans in a city through its (de)construction.

Wendy Gunn’s work is based on the Scandinavian ideal of democracy as “all-inclusive engagement:” including people that would usually be excluded from design and innovation. How do participatory processes compare to that ideal in Rio de Janeiro? The failures of working with inhabitants of Rio’s favelas are a lost opportunity for dialogue and better policy, and lead to poor quality programs, despite the official discourse about integration and participation, especially in the context of the UPP Social program in “pacified” communities.

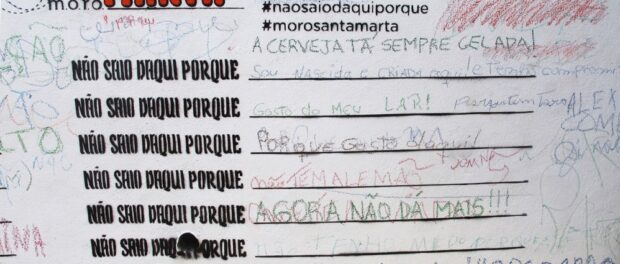

However, resident protaganism does exist in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas, it just takes on more grassroots forms, as exemplified by the “Não Saio Daqui Porque” project, presented during the weekend. Created by university students, this form of interactive art started in Santa Marta and invites community members to list the reasons they do not want to leave, despite threats of eviction or gentrification, directly on the walls of their favela. The reasons vary from “because I like my home,” “because I was born and raised here,” and “because I like it here,” to “because there is no car noise” and “because the beer is always cold.”

Eeva Berglund, an anthropologist from Finland, said that the kind of activism we see is a challenge to the way we view cities. The general discourse on urban activism is about working together and getting our hands dirty, but she affirms that the thinking part is very important. Some design labs want to rekindle the good ideas of the 1960s that were avant-garde then: non-centralized, networked, small-scale ways of designing the city.

Berglund gave the example of a “talkoot,” the Finnish version of mutirão, to preserve an older building in Helsinki: it is not about making profit, or putting it on a CV, or even about saving the planet, but rather about small scale hard work to make a little patch better.

Residents’ visions often clash with city plans, often taken over by large scale construction groups and involving large shopping malls, skyscrapers and highways. Berglund affirms that we increasingly live in a world designed not to fit people but to fit large corporate interests. In Helsinki and in Rio, we can observe a disconnect between “the suits” and “the T-shirts”, between city plans and handmade urbanism initiatives.

Jessica Goodenough is finishing an International Masters in Sustainable Territorial Development and is conducting research on the challenges and qualities associated with the informality of public spaces in Rio’s favelas.