Julio Otoni is a favela nestled between the neighborhoods of Laranjeiras and Santa Teresa in the South Zone of Rio. The entire community is located at a single street address: 298 Doutor Julio Otoni Street.

Arriving at this address, I’m greeted by Sizenaldo Marinho, born and raised in the community and active in a number of initiatives for years. A community center Sizenaldo helped establish in 2004 has offered recycling programs, paper-making workshops, percussion lessons, and tutoring. Sizenaldo has managed classes at the center, coordinating projects with international volunteers. Sizenaldo also represented the community on the Santa Teresa Safety Council. The community center is an important asset in a community lacking in public investment. Unfortunately, Sizenaldo says the center “is closed more than it’s open” lately.

Julio Otoni’s first residents settled in the 1950s, building houses of wood and clay, as well as large bricks available at the time. When Sizenaldo—who now splits his time between a home in Jacarepaguá in the West Zone of Rio and Julio Otoni—was born in 1968, the community consisted of 15 families in 29 houses. In 1986 the government brought basic services—sewerage, water, waste collection, and so on—to the community. Since the 1990s, however, it has expanded rapidly, with growth far outpacing public works to accommodate the larger capacity. Inadequate public infrastructure and services coupled with the surge in population has engendered a sense of neglect for public and community spaces.

Sizenaldo wants to change that: “I want services to enter here. The Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) entered [the community], but other services didn’t.”

Sizenaldo identifies expansion as a major challenge facing the community: “To the contrary of what people think, no community wants to grow more than it has already grown.” Sizenaldo expresses that when communities’ populations surpass the scale for which they were invested, they become “deurbanized” and “dehumanized” as they grow beyond capacity.

Expansion during the 1990s and 2000s transformed the favela into a less familiar place for Sizenaldo, particularly as the drug traffic entered the community. Sizenaldo describes: “The hills started to trade soldiers [traffickers], and a guy would walk in here who has no connection to the community. He doesn’t respect the elders, doesn’t respect the history of the place. His function here is only capitalistic… He’s not here to respect anyone. He respects the capital.”

Julio Otoni’s growth was further fueled by the eviction of 96 houses in neighboring favela Vila Alice, beginning in 2005 and concluding with the removal of the entire community by 2007. Drug traffickers offered the community center in Julio Otoni as squatting grounds for evicted residents of Vila Alice, prompting Sizenaldo to speak up to reclaim the community space for its intended purpose. “A community leader lives on a razor’s edge,” says Sizenaldo. His complaint to the traffickers resulted in death threats forcing him to leave the community in 2006.

As Rio de Janeiro experienced intense real estate speculation in recent years, the demand for affordable housing has surged, particularly affecting centrally located favelas in Rio’s South Zone. Encircled by environmental preservation area (APA) São Jose and wealthy neighboring areas, Julio Otoni has little room for outward expansion, heightening tensions over the right to build in and occupy public and community spaces. While the 2010 census conducted by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IGBE) recognized 231 households and 758 residents in Julio Otoni, Sizenaldo estimates the real figure closer to 400 families and 1,500 inhabitants. The discrepancy likely reflects a combination of three phenomena: incomplete data collection, inaccurate data collection to justify reduced public services for what is truly a larger population, and population growth in the five years since the census was conducted.

Despite the growth, however, Sizenaldo perceives a sense of emptiness. He points to a square at the entrance of the community where popular Festas Juninas (traditional “June Parties”) were once held. Formerly a lively hub for the community, a few small bars and other buildings have encroached on the right side of the plaza; piles of construction materials lie to the left. As Sizenaldo walks further down the road, he runs into longtime resident Regina Celia, who says: “It’s such a good place to live. It’s calm… near everything. But it seems like an abandoned community.” Proudly indicating her bright blue house, Regina says: “I take care of my house. If I had the money to help, I would take care of this place,” pointing to a small plaza containing disassembled playground equipment.

“What the community wants to do,” explains Sizenaldo, “is to reactivate the daycare. There are people who have the capacity to run the daycare once again.” Pointing to the deteriorating building that once housed the daycare center, Sizenaldo identifies a wall dotted with bullet holes. Following a period of violence, residents have enjoyed tranquility in recent years. In operational times, the daycare provided an important function for working families in the community. Currently, squatting tenants—unknown to Sizenaldo—occupy the space.

Lacking public investment in infrastructure and services, residents in Julio Otoni are often left to deal with problems that arise on their own. Indicating a leaning telephone and electricity post on the verge of collapse, Sizenaldo explains: “We send requests to [electric utility] Light, and they don’t come. We send requests to [telephone company] Oi, and they don’t come… Each of these wires is the telephone line of a resident. So when one breaks, we don’t know whose it is. You have to take it [with your hand] from the end of the house, and go until you arrive at the wire.”

While most homes are sturdily reinforced, heavy rains pose environmental hazards for some of the more precarious houses in the community. Three months ago, the foundation of one house began to collapse. Sizenaldo recounts that “people were afraid that they [authorities] would [take advantage of the incident to] come to evict [residents in the house and beyond]” and so they “never called the Civil Defense”—the municipal emergency relief agency. Rather, the family managed to repair the house on their own.

The community only received public investments once—in 1986 during the tenure of Governor Leonel Brizola. On that occasion, the government provided a technician and the materials as part of the “Projeto Mutirão” to address the problem of sanitation, so residents banded together in a mutirão (collective action project) to build the sewer. Yet nowadays, the sewer only services one section of the favela: “The community started to grow more, and the question of sewage returned once again.” Sizenaldo identifies the danger posed by a small stream of open sewage running down an alley: “Kids have fallen here… an elderly woman fell.”

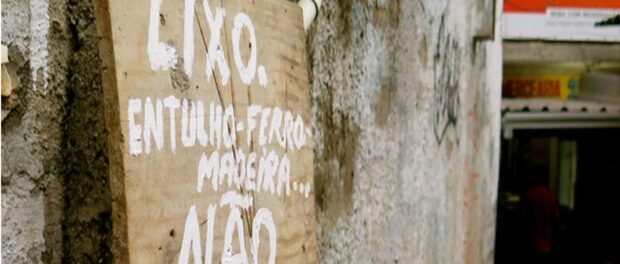

Trash collection (or the lack thereof) poses an additional challenge for the community. In response to the cancellation of the Gari Comunitário—a program in which the City employed local residents as street-sweepers in favelas—one resident, Seu Lima, takes individual initiative to clean public spaces and posts signs around the community that encourage environmental awareness.

These do-it-yourself (DIY) collective and individual actions demonstrate residents’ capacities to create alternative solutions in the absence of publicly provided services. Yet, many of the issues Sizenaldo identifies are large-scale, citywide problems; residents’ resourcefulness does not absolve the City of responsibility for addressing public challenges.