Last Thursday, November 19, Columbia University’s Studio-X Rio hosted Quilombo of the Present / Quilombo of the Future, an event exploring the significance of quilombos today. Held on the eve of Brazil’s Black Awareness Day, the event brought together researchers and practitioners in the areas of history, art, architecture and urbanism to share insights into the spatial and symbolic significance of quilombos in 21st century Brazil.

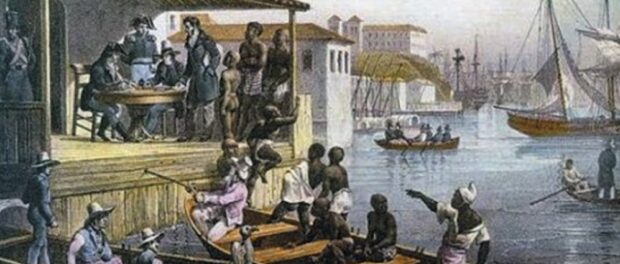

Originally, quilombos were Afro-Brazilian communities established by escaped slaves as a form of active resistance and survival in the midst of Brazil’s brutal and long era of slavery. The Studio-X event description reads: “The quilombo is both myth and reality in Brazilian society. Since the 1988 Constitution, it exists as a territory recognized by the government, but since the emergence of the black movement it is also a symbol of Afro-Brazilian culture. On this eve of Zumbi Day, Studio-X takes asks what does quilombo mean today, both as a physical and symbolic territory in the rural and urban landscape–across the state of Rio de Janeiro to the city center.”

The event was divided in two parts: the first panel discussed the practice of historians who work directly with quilombo communities to document cultural practices and gender relations; the second panel explored the current urban project and African Heritage Circuit in the Port Region of Rio de Janeiro, a site of major significance in Afro-Brazilian history.

Quilombo of the Present / Quilombo of the Future

The first presentation by historian Mariléa de Almeida explored the experience of quilombola women. In her research Almeida has interviewed women leaders at the quilombo communities of Santana and São José da Serra in the south of Rio de Janeiro state, to “make visible the multiple experiences of these black quilombola women in negotiating, translating and problematizing the discussions of their bodies.” Almeida cited that there are officially around 2,400 communities registered as “quilombo remainders” in Brazil, of which only 216 have definitive titles for the land they occupy. She estimated that including communities not officially recognized, the number of quilombos in Brazil could be as high as 5,000.

Mariléa de Almeida discussed the process of “becoming quilombola” and the path of pride that women in these communities traverse in negotiating their subjectivity and power. She highlighted, however, that the history of black resistance is dominated by hero figures such as Zumbi de Palmeres which root black identity in the masculine, heterosexual experience and that dominant narratives dehumanize black women.

The presentation went on to explore the various significances of the cultural practice of jongo, a dance and musical genre originating in quilombo communities, and how these relate to experience, resistance, the body and the process of “becoming quilombola“:

“For some, jongo is a political act; for others there is a religious meaning. Some don’t want to be imprisoned by meanings from the past, others transform them into a spectacle or a practice just for fun. Knowing this highlights that cultural practices and their meanings are constructed by those that practice them through feelings that are always temporary and situational. The incorporation of this knowledge into the historiographic narrative dislocates the focus from the death of a stereotype to the life that pulses in bodies in a way that is subtle, temporary and contingent.”

Historian Hebe Mattos gave a presentation on “Past Presents – The Memory of Slavery in Brazil,” a project that aims to recognize quilombo histories and stimulate a tourism of memory in Rio de Janeiro state.

According to the project site: “Working in partnership with the communities, the project is building permanent exhibitions in the Quilombo do Bracuí, Quilombo de São José da Serra and in the city of Pinheiral. The tourism signs and open air memorials seek to honor the victims of the tragedy of slavery and celebrate the black cultural heritage erected on Brazilian lands by those that survived.” Mattos explained how the project includes a smartphone app to virtually map the places and memory of quilombos in the state of Rio de Janeiro. In the new year, the app is set to include points in the city of Rio itself and in particular the Port Region, the port of arrival for two of the ten million enslaved Africans brought to the Americas.

The Port Region today was the focus of the second part of the event which opened with a presentation by Clarissa Diniz, assistant curator of the Museum of Rio Art located in Praça Mauá in the Port Zone. “The role of the museum is to think about the history of Rio and propose different readings of the issues and territories,” she said. Diniz presented images of the museum’s main exhibition of 2014, “From Valongo to Favela: The Imaginary and the Periphery,” which connected Rio’s slave past with the favelas today. She argued, “To speak about a territory you have to de-territorialize and explore other situations and equivalences.”

Presenting Rio’s African Heritage Circuit

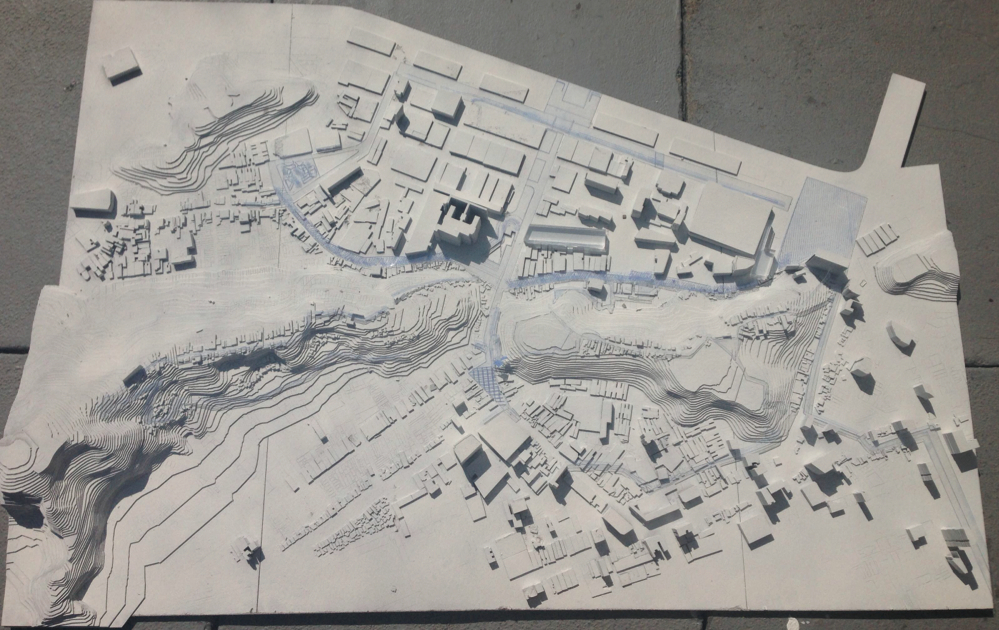

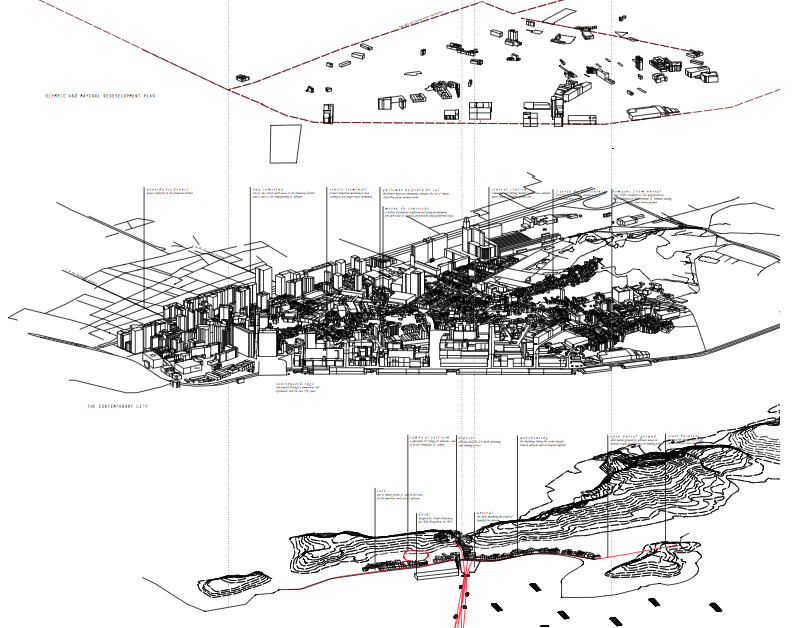

The next speaker was Sara Zewde, an American landscape architect and urban planner who received the prestigious Olmsted scholarship to develop the design for the African Heritage Circuit in the Port Region of Rio, the subject of her Masters thesis in Landscape Architecture at the Harvard School of Design. Zwede is currently working with the city government’s Rio World Heritage Institute to implement the project.

In a detailed presentation, Zewde presented her methodology and experience of developing the African Heritage Circuit, from the initial question of how to design a project that honors the black experience and her subsequent research and design work around the history of the Port region and Afro-Brazilian traditions, to concrete plans for implementing the Circuit.

Zewde argued that the traditional model of a memorial or statue would be inappropriate for honoring the Afro-Brazilian experience: “Afro-Brazilian memory in the Valongo slave market is a cultural memory which causes tension in the limits of the concept of a memorial. Because of this it must break with the architectural traditions of a memorial.”

The theoretical framework developed for the Circuit explores the concepts of non-linear time in Afro-Brazilian spiritual traditions, Afro-Brazilian performance arts such as capoeira and dance, and delineations of space in Afro-Brazilian culture and the interplay between emotion, experience and everyday life.

Analyzing the site in the Port Zone known as Little Africa, Zewde discovered that millions of years ago the Valongo slave market touched the current West African coast and until today the land has the same type of soil and plant characteristics. As well as cultural traditions, enslaved Africans actively brought plants on ships which flourished in the new lands.

In a series of maps and diagrams, Zewde explored both the historic geography of the region according to the movement and experience of enslaved Africans, including the port of arrival, warehouses, slave markets and hospital, and visual representations of Afro-Brazilian cultural traditions such as capoeira and samba rhythms.

Of the Circuit Zewde said: “It is a constellation of projects interwoven in the everyday spaces of Little Africa and the large Port Zone to highlight and frame these cultures.” The vision and suggestions for the Circuit include a recognition and preservation of the Valongo archaeological site, design features highlighting the plant species brought by enslaved Africans and a potential new square incorporating a layer of water to give the sensation of walking on the sea, honoring the spiritual significance of water in Afro-Brazilian religions and the journey across the ocean from Africa.

The final speaker was architect Washington Fajardo, president of the Rio World Heritage Institute, who spoke of how the idea of heritage is a relatively recent concept in Rio’s history, only starting to gain traction in the 1970s and 80s. Of the plans to develop the African Heritage Circuit he cited the importance of consolidating tourism activities by Afro-Brazilians in the region and strengthening the economy of the Circuit.

Fajardo posed questions as to the representation of the black experience in public spaces: while much of Rio’s historic architecture was built by Afro-Brazilians, it is a representation of white, colonial Brazil. “What is the representation of black people in the city?” he asked. “We need to bring this debate to the issues of territory and access. The territorial dimension is far from resolved and must advance.”

The event concluded with DJ sets of African-Diasporic rhythms by DJ/producers Chief Boima and Maga Bo.